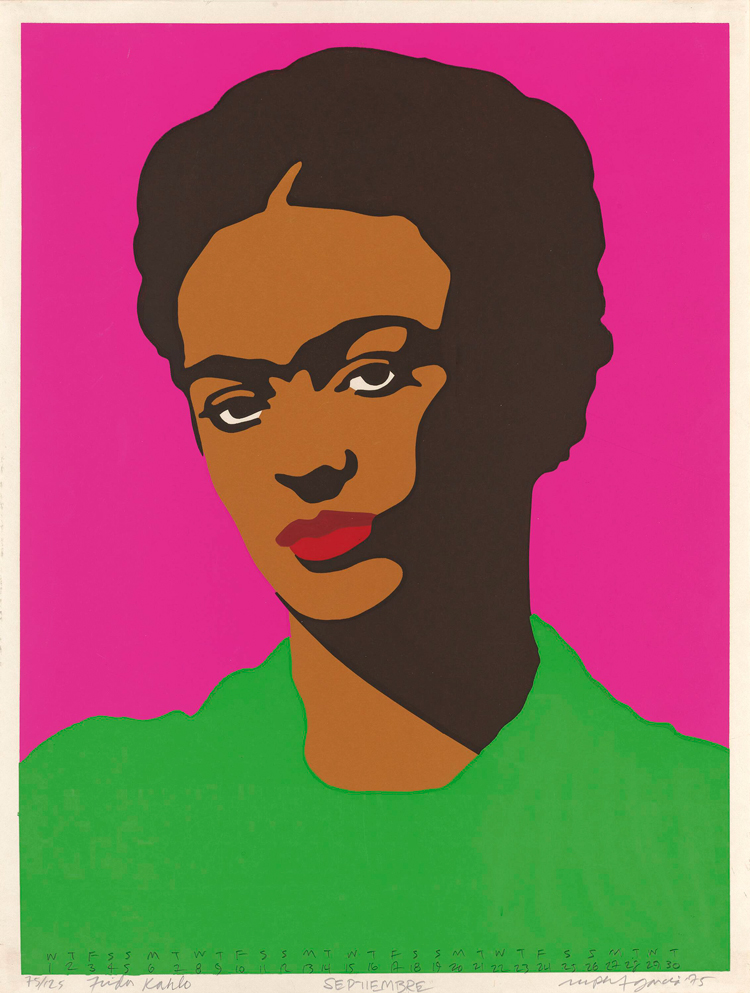

The Queer Magic of Frida Kahlo

New MFAH exhibit tracks her influence across art and identity.

In the early 1980s, Mari Carmen Ramírez was a young scholar spending time in Mexico when she discovered artist Frida Kahlo. At the time, Kahlo was undergoing a newfound popularity.

Fast-forward to the present, and Ramírez is now the Wortham Curator of Latin American Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), and curator of the exhibit Frida: The Making of an Icon. And Kahlo, far from the unknown local artist she once was, is now a worldwide phenomenon with hundreds of exhibitions of her work, thousands of artists claiming her as an influence, and a self-portrait, El Sueño (La Cama), that recently sold for $54.7 million at a Sotheby’s auction.

When Ramírez began organizing the MFAH exhibit, she decided against a Kahlo retrospective, choosing instead to focus on how Kahlo went from an unknown artist to a global icon who is claimed and admired by multiple communities.

“We’ve had many, many retrospectives of Frida Kahlo; we don’t need one more. Plus, it’s extremely difficult to get her work. So I decided to focus on how this phenomenon unfolded,” Ramírez tells us. “She went from being an alternative figure who was rediscovered to being appropriated by feminists, Chicanos, the LGBTQ community, and then by contemporary artists.”

Ramírez originally planned to create a historical exhibit focusing on the 1980s and ’90s, decades that were so crucial to building the icon. But then Ramírez was impressed to see how much growth continued after 2000.

“I was surprised to see how relevant she continues to be today. She has now spawned a new movement of disability art. So even now, her influence continues to change and shape new artists.”

There are 30 works by Kahlo and some 120 works by 80 other artists in the show who all have a relationship to Kahlo, and recognize her as the starting point to their own work.

Ramírez quotes Rosalie Favell, a well-known LGBTQ Métis artist whose work is included in the MFAH exhibit. Discussing Kahlo’s influence on her own work, Favell says, “The fact that her work was autobiographical was a huge part of my attraction. It was like she ripped out a part of her soul, her pain, her reality, and laid it out for others to see. Her work gave me courage. Her intimate paintings gave me permission to share my feelings and my experiences.”

As global as her reach is now, Kahlo was not always well known or influential. When Kahlo died in 1954, she had a devoted—albeit small—circle of fans and collectors, but she had always lived in the shadow of her husband, the legendary muralist Diego Rivera.

Until the late 1930s, she did not consider herself a professional artist. During her lifetime, she had only two solo exhibitions and sold only a handful of her works.

“We’re not talking about a professional artist who was developing from art school on. It was not until the 1970s when her biographies were published that she became well-known,” says Ramírez. “You had male icons and deities like Pablo Picasso and Andy Warhol. Now Frida has surpassed all of them in name recognition. Everyone in the world knows who Frida is. There are Frida look-alike contests all over the world. There are more than 100,000 objects on Amazon and Etsy that have her image, including sanitary napkins,” Ramírez says, laughing at the absurdity.

A downside to the enthusiasm for Kahlo’s rediscovery was that the market created a stereotype of her. She was seen as representative of all of Latin America.

“Frida is the exception, not the rule,” says Ramírez emphatically. “People who are new to Latin American art look to Frida’s work, but her art cannot be taken as representative of an entire continent made up of 33 countries.”

For a while, Ramírez was the honorary president of the anti-Frida club. “We couldn’t allow that narrow vision of Latin American art to overwhelm the reality of there being so many other artists, so many schools,” she admits.

While Kahlo does not represent the entirety of Latin American art, she has a unique position in its history. “The most important thing is that she has stimulated something that I have never seen with any male artists, which is the desire of artists, both male and female, to embody Frida, to dress themselves as Frida,” says Ramírez. “They paint themselves as Frida. This is unheard of. She definitely has a certain magic to her, and she has the power of endurance to her.”

Everything that Kahlo did was deliberate, Ramírez tells us. Kahlo constructed and projected her image in a very particular way. And it wasn’t just one image. “She was a flapper. She was an avant-garde artist and intellectual. She was a devoted wife. She was a modern-day woman. She was a bisexual woman. All of these factors converge and become what we know as Frida.”

WHAT: Frida: The Making of an Icon

WHERE: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, 1001 Bissonnet St.

WHEN: January 19–May 17, 2026

INFO: mfah.org