A Legal Eagle Fighting for Equality

Phyllis Frye, Houston’s first transgender lawyer and judge, reflects on her life and legacy.

Phyllis Frye has never been afraid of a fight. Her name has been synonymous with the transgender community’s determination to include the T in LGBTQ, and her rise to legal prominence has been nothing short of historic. Known as “the grandmother of the nation’s legal and political transgender community,” Frye possesses a soft side marked by love and caring despite her aggressiveness in the courtroom and in politics.

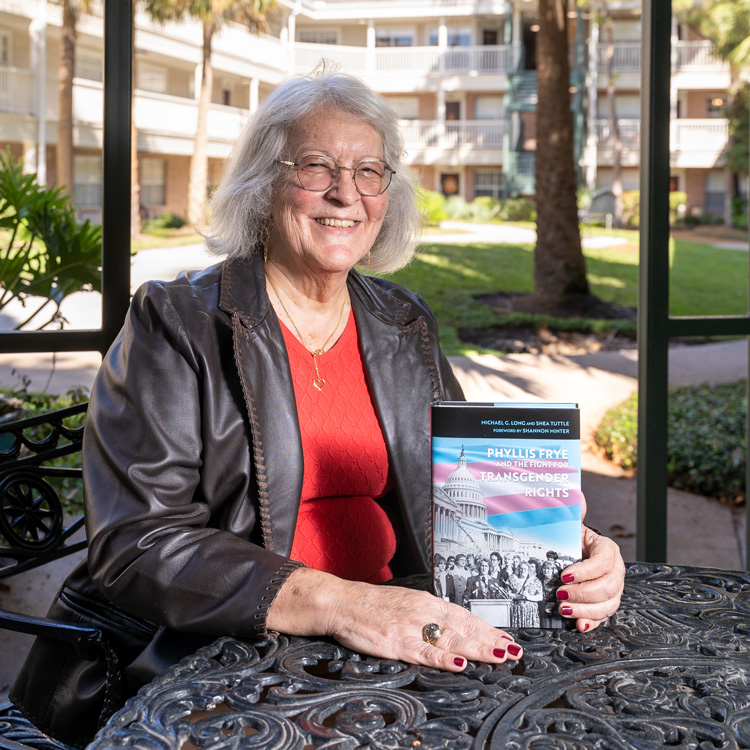

The many facets of Frye’s life and times can now be better understood thanks to an authorized biography written by Michael G. Long and Shea Tuttle, with an introduction by Shannon Minter and published by Texas

A&M University Press. Phyllis Frye and the Fight for Transgender Rights is a 268-page tour de force that examines Frye’s sexuality and gender, as well as her struggles and triumphs in bringing transgender issues to the forefront of public thought.

“The name of the book includes ‘The Fight,’ and I won. If you read it through to the end, you’ll see that I won,” Frye says.

And fight, she did. Frye has fought for nearly every job, relationship, and professional recognition in her life—battles that are spelled out in full detail, including several expletives to punctuate the less-than-easy road she

has traveled. Though the road was rocky, she quickly paved a smoother path for those who followed her example of tireless activism.

Though Frye is a well-known attorney, her entry into law school was more a matter of circumstance rather than choice. Trained in the military and a double graduate of Texas A&M University’s engineering programs, Frye was content to live a life working in the oil and gas industry. However, her fondness for dressing in women’s clothing and Christian proselytizing during work hours (despite her male-presenting body at the time) proved too much for her employers and coworkers. She was usually relegated to menial work and eventually forced out of several jobs.

And that is what led to her second career in the courtroom.

“I became a lawyer by accident,” Frye admits. “Once I started to transition in 1976, I had been pretty much not only fired, but black-balled by the Houston engineering community because they weren’t going to put up with this queer person who was a guy and was becoming a woman. Because I had an honorable discharge from the military and had access to the G.I. Bill, I thought I could earn a master’s in business administration because [it would buy me some time while I was unemployed]. And probably, in those classes there would be some young engineering manager types who will get to know me as a person instead of ‘a thing,’ and I might be able to land a job.”

Frye enrolled at the University of Houston just as the school was introducing a joint MBA-JD program. In Frye’s eyes, that program would buy her even more time to lean on the G.I. Bill for income. Plus, she knew a lawyer could fight back and address the injustices that trans people were constantly facing at the time.

“I thought that if I become a lawyer, maybe I could sue [the people who were] just making my life miserable. That’s the reason—and the only reason—that I went to law school,” she adds with a sly grin.

An excerpt from page 96 of the book succinctly captures Frye’s early battles and subsequent successes in raising awareness of transgender equality issues:

While finishing law school, Phyllis felt a deep sense of accomplishment. First, she had been accepted to law school despite the fears of some professors and administrators. And then, during her course of study, she had overcome resistance to her use of women’s bathrooms, lobbied City Council for the repeal of the anti- cross-dressing ordinance, helped inject transgender issues into the 1979 National March for Lesbian and Gay Rights, joined in marches and rallies where she constantly raised the issue of transgender rights, won her first court fight for a transgender woman, battled the bigotry of the district attorney’s office, formed friendships with judges and attorneys, silenced the Christian Legal Society, and raised her grades. Perhaps most importantly, she had grown confident in her identity as a transgender woman.

Frye’s story is one of persecution, pushback, and eventual victory. She’s also the first to tell people that her success was partially due to the friendship and love of her partner for 48 years, Trish, who passed away in 2020 from a brain tumor.

“I had a wonderful companion and wife named Trish, to whom the book is dedicated. I could not have done this without her support. Whenever I would be down, she would console me. Whenever I was confused as to what to do next, I would consult with her. During those periods of time when I could not get work, her income was our sole and only income. We were terrified her employer would find out that she was married to me and she would lose her job. But that persistence and self-pride is what people will find out by reading the book,” Frye explains.

One of Frye’s lasting accomplishments was the International Conference on Transgender Law & Employment Policy, a series of conferences from 1992 to 1996.

“This was the beginning of the national legal and political movement of the transgender community. We had lawyers and judges come and speak at the conferences. And we had, at first, a few transgender lawyers who were not out. But as time went on, others started going to law school.

[I educated and inspired] a lot of the people who came to the conferences about things they could do as non-lawyers to generally raise hell where they lived. It just grew and grew and grew,” she emphasizes.Hell raiser or groundbreaker? The book suggests Frye is a little bit of both—or at least enough to earn the attention of Annise Parker, another Houston-centric LGBTQ icon who was the city’s first openly lesbian mayor.

Parker and Frye had a long-standing relationship in local activism, so, given Frye’s work in the legal field, it was not a head-scratcher for Parker to invite Frye to become a municipal judge. Frye willingly accepted the position as an associate judge in the Houston Municipal Courts, which made her the first openly transgender judge in the world.

Frye mentions that most of her cases involved traffic disputes, but one of the highlights of her job was to marry couples—and especially LGBTQ couples after marriage equality became the law of the land.

“When same-sex marriage became legal, I performed a lot of same-sex marriages. I would meet gay couples who had been together for a long time, and they would say they would like to get married but couldn’t afford a huge ceremony. I would tell them they should get married in a courthouse, for the legal protections. They would come to my office with a marriage license, and I’d marry them so that each person would be protected by law. I did a lot of those, and that was very satisfying.”

After a career that has stretched well into her seventies, the tireless judge is eying her retirement from the bench.

“I am stepping down from the bench because 12 years is enough. I’m going to be 75, for goodness’ sake! I am enjoying my life.”

She does have plans for life after her career—such as continuing to advocate for the transgender community, and especially for those entering their senior years.

“Most transgender people don’t have surgery below the waist. It’s expensive as hell, and most can’t afford it. That’s okay when they’re young, but when they start getting old and looking at hospitalization or nursing homes or hospice, it’s different. They appear one way above the sheets, and they appear another way below the sheets. The people who work with their catheters, bathe them, or change their gowns—they’ll start misgendering the patients. It is a microaggression,” Frye notes.

“Transgender elderly people need to be treated with respect for their gender. They don’t need to be constantly reminded, by people who use the wrong pronouns, of where they came from. That’s something that’s going to be a long-term goal. Every time I get paid to speak, I always bring up the issue of transgender elderly people,” she says.

As Frye dives into retirement in January 2023, one thing will always remain true: she has unquestionably lived her truth, and was a driving force to make sure there was a T in LGBTQ.

Phyllis Frye and the Fight for Transgender Rights is available on Amazon and wherever books are sold.