A New Cinematic ‘New Wave’?

Gay films of the 1990s.

Gay films of the 1990s.

by Kit van Cleave

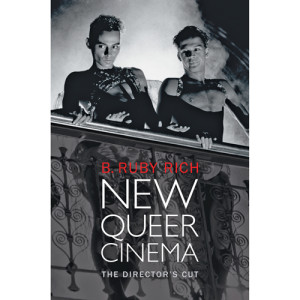

In her new book on gay films of the 1990s, New Queer Cinema: The Director’s Cut, B. Ruby Rich predicts the continuation of a new kind of filmmaking, “an approach in search of new languages and mediums that could accommodate new materials, subjects, and modes of production.” This could indeed be an evolution in thinking, as many films she discusses were a revolt against gay discrimination during the AIDS crisis.

Rich suggests that her book “also records my own participation in [a] founding moment, for I had the privilege of christening the New Queer Cinema way back in 1992.” As Professor of Film and Digital Media at University of California, Santa Cruz, Rich has been active in both gay community projects and as a critic of film for the Village Voice, SF Weekly, GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, Sight and Sound, Out, Film Quarterly, and San Francisco Bay Guardian.

Many of the articles in this anthology have been published elsewhere, but Rich saves us from having to search the archives. She gives notes and commentary at the end of each piece, and cites the original publication source.

Rich provides a masterful decoding of Brokeback Mountain (2005), for which director Ang Lee won the Grand Prize at the Venice Film Festival, “just as Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal were accepting wild ovations” from crowds at the Toronto International Film Festival. Lee then won the Oscar, BAFTA, and Golden Globe for Best Director that year.

Set in 1963, this “great love story,” as Rich tells it, is really about the “torture chamber of a society’s intolerance and threats, and individual’s fear and repression.” These were the end-days of U.S. gays having to keep their heads down and their behavior discreet for fear of jail, prison, or death—just for living authentically. It was the same path trod for decades by African Americans, Latinos, Asians, and women in America. Rich provides an eloquent timeline leading up to this film, and records “the crack of the Earth splitting open and [cinema] history books rewriting themselves.” The movie was truly historic—and heartbreaking.

Among the many excellent chapters, my two favorites were those covering gay women’s films and French movies of the past and present.

Chapter 15, titled “Lethal Lesbians,” recalls the era when lesbian characters always had to die at the end of the movie because they were mentally disordered and dangerous. I always found this hilarious, and even interrupted many a dramatic moment by bursting into laughter when (for example) a tree fell on Sandy Dennis in The Fox (1967) or Shirley MacLaine’s feet dangled in front of Audrey Hepburn’s horrified eyes in The Children’s Hour (1961).

Rich then moves into the “Lesbian Chic” era of the 1980s and 1990s, beginning with one night in 1988—the magic moment when Madonna and Sandra Bernhard appeared on CBS’s David Letterman Show dressed in matching outfits to carry out a highly effective plan to spook both the host and the audience. They flirted, they danced, they bantered, and when asked how they spent a typical night out on the town, they shouted, “Cubby Hole,” the name of a popular Greenwich Village lesbian bar.

Shortly thereafter, the official LC era began, with kd lang on the cover of New York Magazine and Newsweek’s “Lesbian Chic” cover story. Rich analyzes in detail the back-to-back glass-ceiling-breaking Thelma and Louise (1991) and Basic Instinct (1992), and touches on Charlize Theron’s Oscar-winning Monster as well. All of these films reflected a new emphasis on women’s power, autonomy, and dangerousness. (I strongly encourage Basic Instinct fans to purchase the special-edition DVD that features a commentary track by critic Camille Paglia discussing how Sharon Stone represents woman’s energy overcoming man’s. It’s a real eye-opener.)

Chapter 26, “Queer Nouveau,” emphasizes the work of Francois Ozon, Andre Techine, and Cyril Collard, all gay male filmmakers who have brought new ideas to the French artform. “In early histories of gay and lesbian cinema . . . France played a prominent role” due to the influence of Jean Genet, Jean Cocteau, and Chantel Akerman, who defined France’s pre-queer cinema for decades. Rich points out that “these films became shorthand for an international fascination for sex and romance à la français, all twisted bisexuals and glamorous more-than-friends included.”

She rightly states that by the 1990s, France was better known in LGBT circles for “actress idolatry [Catherine Deneuve, Delphine Seyrig] and philosophy [Monique Wittig, Michel Foucault] than cinema.” Thus, the arrival of these three new directors was cause for celebration. Inexplicably, Ozon, the youngest and most commercially successful filmmaker, is not credited in Rich’s book for his terrific 8 Women, which includes some clothed girl-on-girl action between Deneuve and Fanny Ardant.

For a variety of reasons, Paris has become the artistic epicenter of world cinema; Hollywood is for the profit-only boys. Thus, Rich’s comments on the current French movie industry are timely and incisive. I’m sure I’m not the only one waiting for the explicit Blue Is the Warmest Color, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes earlier this year, to appear at River Oaks Theatre. It shocked the audience, but won the judges over.

Kit van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Montrose. She has published in local, national, and international media.

FB Comments