It’s a Holiday!

The origins of black gay history. Plus a month of gay history heroes.

By Kevin Mumford, Gay History Project

See also History, Herstory, Your Story: GLBT History Month

The idea of Black Gay History is about as far out there for some as is Gay History Month, and the two curiosities are not unrelated. The first attempt to set aside a time to disseminate information on minorities was Negro History Week, invented by the black (straight) historian Carter G. Woodson around 1926. He chose February to honor the births of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, and he and his students lectured to clubs and fraternities, sponsored essay contests, and published popular textbooks. The impulse to reach a wider audience and instill pride caught on with Women’s History Week, and then month, and so now let there be Gay History Month. Why not?

This could mean that queer scholars of color will have more opportunities to teach their lessons, but my fear is that we will have none. This sort of anxiety was at the heart of the first efforts to construct a black gay history, from Melvin Dixon to Barbara Smith, and dozens of lesser-known writers. More than 20 years ago, a black gay journalist, Robert Grier, wrote a column for Au Courant (a newspaper that consistently covered Philadelphia’s vibrant black gay life) entitled, “Black History Month? Why Gays Don’t Exist.” He disparaged books that “communicate to the black straight community that black gays are not/no longer contributors and resultantly expendable.”

New York activist Craig Harris was angrier. “Many consider our history unworthy of scholarly attention,” he wrote in 1986. He called out by name black historian Lerone Bennett Jr. and gay scholar Jonathan Katz for refusing “to embark upon the discussion of our complete history. They supply us with half-truths.” Harris went on to describe in detail the contributions of black gays and lesbians, displaying a learnedness that was common, even constitutive of black gay men of the 1980s. He likened white historians who dabbled in the black gay past to “the presence of intruders.”

History was the favorite subject of the star high-school student Joseph Beam, who became a black gay luminary among Philadelphia cultural activists (1954–1987). Everyone who encountered Beam recalled the depth of his intensity—a carefully controlled rage at invisibility. He wrote dozens of unusually moving essays, mentored artists and writers, and edited In the Life , the first anthology of black gay writings. On history, Beam wrote about how he had to “create myself from scratch as a black gay man living in the late 1980s.” He explained that in the 1970s, he enrolled in graduate school in Iowa, and “spent so much energy in self-observation” that he dropped out of the program. “I need heros [sic], men and women I could emulate.” He later returned to Philadelphia and rented a studio apartment off Rittenhouse Square. “I needed to create images by which I, and other black gay men to follow, could live this life.” In another Au Courant column, he observed that “to endure with any safety, I must be a historian, librarian, and archeologist, digging up and dusting off the fragments of black history and black gay history.”

Barbara Smith, another visionary of black queer history, came up with a metaphorical salve for the likes of Beam. Smith had attended the New York funeral of James Baldwin (1924–1987) and described the eulogies to him by America’s most important writers Amiri Baraka and Toni Morrison, neither of whom mentioned his obvious gayness. It was a remarkable omission, because not only had he written queer novels, but he came out publicly some five years before at a lecture sponsored by Black and White Men Together. Smith imagined how telling the truth could help black queers “all over the globe,” and satisfied herself with the prospect of future ceremonies. In a revelation, Smith told us that “we must always bury our dead twice.”

As an African American and gay historian, I have felt some of this double mourning. Even the most radical or progressive black history textbooks, such as Nell Painter’s Creating Black Americans or Robin Kelley and Earl Lewis’ We Changed the World , completely omit any and all mention of homosexuality. To open a textbook to the New Negro or the Harlem Renaissance, and not identify gay or bisexual folks, is like reading about the Civil War but not learning that the South had slaves. When black communities speak out against the inclusion of GLBT history in their local schools, who can blame them? Where would they learn better?

Unlike the moment when Beam and Harris wrote in despair, there is much to read on black gay history. Professional monographs, journals, and dissertations abound. We know that Alain Locke mentored black gay graduate students, who went on to work as social workers in prisons, at the same time that he helped to invent the historic movement known as the New Negro. In my first book, I discovered documents pertaining to Wallace Thurman (1902–1934) that were ignored by scholars for decades. Thurman, a major novelist who vividly portrayed gay life, confided to a friend that he was arrested for solicitation of another man in a Harlem restroom. Richard Bruce Nugent has told his story of black gay life to every generation, but his last novel was published only this year, with an introduction by the controversial biographer Arnold Rampersad, who had long refused to acknowledge the gay desires of Langston Hughes. They were all black, queer, and pivotal—without question.

As every historian knows, attitudes and beliefs change in response to larger trends and events. Indeed, looking back at the black community in the 1920s and ’30s, one sees remarkable openness to gays and lesbians, and then how some of the tolerance gave way to postwar homophobia. Some new scholarship suggests that Martin Luther King Jr.’s civil-rights demonstrations were premised on a demand for strict respectability, not only cleansing the movement of radicals and communists but also what were known as sexual deviates. Yet by the 1970s, many black progressives protested for gay and lesbian rights in New York City and Philadelphia. The first out black gay Catholic, Grant-Michael Fitzgerald, was a brother in the Society of the Divine Savior and, in that capacity, helped to pass a resolution at a national conference of priests to extend pastoral services to gay and lesbian laity. In 1974 before the Philadelphia City Council, Grant-Michael powerfully refuted black religious testimony against gay rights, and in Milwaukee he appeared in his characteristic black suit and clerical collar on a television talk show to make the case for gay rights, black gay power, and gay fostering and adoption (he was a licensed foster-care parent in the state of Wisconsin). As a biographer of Fitzgerald, my research leads me to an inquiry into the human trait of courage. Where did he find the courage to speak out when many of his generation felt the oppression of silence?

On the other hand, merely adding gay history to the calendar is not a guarantee for inclusiveness. It is true that in the aftermath of the Stonewall riots, white and black gay men felt radicalized and shared an identification with black people’s historical experiences. If Black was Beautiful, Gay was Good. In 1976, the Philadelphia Weekly Gayzette , an activist publication, ran a story about black history month, which they described as “a time for celebrating the history of a people which was kept hidden by racism and bigotry.” Their point was that “gay people have a special link to black people and the Black Liberation Movement.” But they truly honored black history month by taking the time to criticize unfair practices in the gay community. “The racist policies at the bars are shocking. Yet racism is one problem which is given only lip service in most gay liberation groups. More black sisters and brothers are being oppressed on all sides.”

GLBT history is a relatively new field, and feels vulnerable—and black gay history confronts it with difficult stories of racism. It is a momentous time when the dean of gay history, John D’Emilio, chooses to spend more than a decade to devote to the biography of a black gay man, Bayard Rustin. The fact is, in America, gay worlds have always turned on the question of race—on the construction of whiteness, on racial segregation of leisure, on the performance of stereotypical spectacle. Over the past 20 years or so, countless awards, endowed chairs, and learned distinctions have gone to historians who take seriously the mercurial power of race. Yet it is not an exaggeration to argue that gay and lesbian historiography remains one of the whitest fields in the discipline. More celebration under the rainbow flag won’t correct our errant ways.

Kevin Mumford is associate professor of History and African American Studies at the University of Iowa. He is the author of numerous reviews and articles about race and sexuality, and of Interzones: Black/White Sex Districts in Chicago and New York in the Early Twentieth Century (Columbia University Press, 1997), and of Newark: A History of Race, Rights and Riots in America , (New York University Press, 2007).

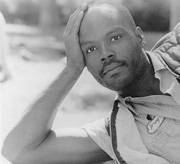

Photo caption : Even though he was instrumental in organizing the historic 1963 March on Washington, in which The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his inspiring “I Have a Dream” speech, King’s openly gay advisor Bayard Rustin (r) was often eschewed by the very people he was helping to liberate. This 1956 photo shows the two men in Montgomery, Alabama, in support of the bus boycott sparked by Rosa Parks.

_____________________________

GLBT History Month

Each day in October, the Equality Forum will feature a GLBT icon online with a video, bio, and more at www.glbtHistoryMonth.com. Check out the pioneers who’ve helped us get where we are today, and various other movers and shakers who are giving us a vision for our future. Here’s who’s featured this month.

1

Del Martin & Phyllis Lyon

Founders, first lesbian organization & first same-sex couple married in California

2

Stephen Sondheim

Lyricist & composer

3

Gianni Versace

Fashion designer

4

Sheila Keuhl

First openly gay member of the California Legislature

5

Tennessee Williams

Playwright

6

Alice Walker

Author

7

Greg Louganis

Olympic gold medalist

8

Bertrand Delano

First openly gay mayor of Paris

9

Margaret Mead

Anthropologist

10

Mark Bingham

9/11 hero

11

Cleve Jones

Founder of NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt

12

Jann Wenner

Publisher

13

Harvey Fierstein

Playwright and actor

14

Margarethe Cammermeyer

Military officer and activist

15

Anthony Romero

ACLU executive director

16

Melissa Etheridge

Singer-songwriter

17

Gene Robinson

First openly gay Episcopal bishop

18

John Waters

Filmmaker

19

Robert Mapplethorpe

Photographer

20

Georgina Beyer

First transgender member of

a national legislature

21

Tony Kushner

Playwright

22

Rosie O’Donnell

Comedian

23

Philip Johnson

Architect

24

E.M. Forster

Author

25

Randy Shilts

Author and AIDS chronicler

26

Allen Ginsberg

Poet and activist

27

Troy Perry

Founder, Metropolitan Community Churches

28

Bill T. Jones

Choreographer

29

Andy Warhol

Artist

30

Rachel Carson

Environmental pioneer

31

Michelangelo

Renaissance painter, sculptor, and architect