Larry Bagneris: The Black Activist Who Gave Houston Its Pride Parade

The New Orleans native organized the first LGBTQ celebration in 1979.

Larry Bagneris should be a name that’s widely known throughout Houston’s queer community. After all, he is responsible for originating the city’s first Pride parade. He was also the first elected Black president of what is now the Houston LGBTQ+ Political Caucus. Despite these hefty credentials, the 75-year-old’s name does not loom as large as other LGBTQ luminaries like Annise Parker, Phyllis Frye, or Ray Hill—all of whom he has worked alongside. That is about to change.

“Shortly after I moved to Houston [from New Orleans] in 1972, I brought my sister, Gina, to see the Foley’s Thanksgiving Day Parade when she was about 8. I was so excited for her to see it, and I looked down and asked her what she thought. She said, ‘It’s boring.’ She was right. It dawned on me that the gay community needed to do a parade and make floats and throw beads to really show them how it’s done,” Bagneris recalls.

This idea stayed with him over the years as he became more involved with Houston’s LGBTQ community, which at the time was the epicenter of queer politics in the South. The Caucus, which was then known as the Gay Political Caucus (GPC), was at the forefront of queer community organizing and slowly built political clout in the late ’70s and ’80s. Bagneris would go on to lead that organization in 1982, but his commitment to fighting for civil rights began many years before that.

Unearthing a Lost Story

Local activist Harrison Guy is largely responsible for the re-emergence of this Houston icon. Guy founded the Charles Law Community Archive in Houston’s African American Library at the Gregory School in 2019. The Law Archive focuses on the stories of Houston’s queer Black community.

When Guy was named one of Houston’s Pride grand marshals in 2019, he decided to dig in and research Bagneris’ story. “When I was up for grand marshal of the 2019 Pride parade, I started going through all of the archives to see if any other Black men had come before me. I wanted to make sure that I acknowledged them for paving the way. I was shocked to learn that I would be the first. Someone mentioned that it was ironic that a Black man had never won, considering the parade was started by a Black man. I said, ‘Excuse me?’ So I got to researching, and found out that Larry Bagneris was in New Orleans. I immediately hounded all of my friends in NOLA to get me in touch with him, and I was able to get his email.”

Once they connected, Guy organized a recorded sit-down interview with the Houston icon that streamed on OutSmart magazine’s social media. Finally, a piece of Houston history that had disappeared into the ether had an opportunity to be told.

“I can remember attending the Pride parade for years and feeling like it wasn’t for me,” Guy admits. “Imagine if I had known that Blackness was a part of its founding. I am a firm believer that we cannot move forward unless we first tell the truth about where we are and where we’ve been. Sharing Larry’s story allows us the opportunity to acknowledge Black contributions and learn from erasure, in the hopes that this will help us to move forward.”

From New Orleans to New York City

Bagneris, who grew up in New Orleans, picked up his first picket sign in 1962 at age 16. That was in front of the Maison Blanche department store on Canal Street, where he joined a protest to condemn the store’s racist treatment of Black people during the height of segregation.

His struggles as a Black man in America were compounded by his internal struggle with being gay. At first, he tried to resolve those feelings through his church. He was concerned about attending an all-boys school, where he might do something that would reveal to others that he was gay. Having no success at church, Bagneris paid a psychologist to help him sort through his feelings. That doctor recommended shock treatment, and Bagneris knew that wasn’t the answer. He told that doctor to “shove his shock treatment up his ass” before walking out and hopping on a streetcar. But before he got home, he encountered the Maison Blanche protesters on Canal Street.

“I saw the protest and I thought to myself, ‘Okay, let’s take care of this [Black] problem, and then we will get to [gay rights] in the future.’ I knew there would eventually be a movement for people like me,” Bargneris says.

The young Bagneris discovered early on that due to his age he could avoid jail time whenever he was arrested at protests. He was emboldened by this fact, and became even more active in the civil-rights movement.

Then in June of 1969, a gay professor and friend took him to New York City, where Bagneris found himself at the Stonewall Inn just a few weeks before it would become the birthplace of the modern-day LGBTQ civil-rights movement.

“The diversity of the crowd was amazing,” Bagneris recalls about his night at the Stonewall Inn. “Puerto Ricans, drag queens, transgender people—all in this melting pot. The tribal music and the lights were such that I thought I had found heaven. And then the lights came on suddenly, and this guy that I had been dancing and having drinks with grabbed me by the hand and said, ‘Let’s go! This is a raid!’ We climbed out of the bathroom window onto the patio and climbed a ladder over the fence. I started crying, and I said, ‘This is like West Side Story!’ [My friend just replied], ‘If you don’t move your ass, you’re gonna get arrested.’’ It was a magical awakening for the young New Orleanian.

The next day, Bagneris realized that if he had been arrested, his life would have been ruined. In the late ’60s, being arrested for the “deviancy” of being gay could cause you to lose your job or prevent you from ever getting hired. And as a gay Black man, he was even more suceptible to discrimination. He bravely decided that there was no choice but to join what was about to become “The Gay Rights Movement”—which itself was not immune from racism.

Houston Beckons

That pivotal summer of ’69, Bagneris got his degree in political science from Xavier University and moved to Houston to take a public-relations job at Foley’s department store. Bagneris chose Houston because it was one of the few “gay meccas” in the country. Once here, he was introduced to queer organizations like The Diana Foundation and the Caucus, both of which are still around today.

“I saw the presence that the Caucus had. I decided that’s where I needed to be. That’s where the power was. This was now 1977, [so we were preparing] for Town Meeting I and the March on Washington in 1979.”

Bagneris was able to rise through the leadership ranks of the Caucus by building a coalition made up of diverse members of the queer community. He was often mistaken for being Latinx rather than Black. This may be why he is also considered responsible for developing the first gay Chicano political caucus.

Former Houston mayor and LGBTQ activist Annise Parker recalls the broad coalition of people that Bagneris was able to cultivate. “When I picture Larry from back then, I see him in green Army pants and a really tight, white T-shirt with an Army-green cap on his head—and black combat boots,” she says. “That’s how I picture him, but he also got up every day and put on a suit and tie and sold insurance. Larry couldn’t have cared less about running for office. He was very much a truly independent player, and a chameleon. He could effectively move in different circles. In some ways he was always an outsider, but he could also fit into many different groups as well. That’s part of what made him successful.”

In 1979, he became the vice president of the Caucus and eventually president in 1982. It was during his tenure as vice president that he put into motion the idea that his sister sparked in him at the 1972 Thanksgiving Day parade—to organize Houston’s first Pride parade.

Battling at City Hall

Strategy has always been one of Bagneris’ special talents. He knew he would need parade permits from the City, and at the time those were doled out through the police department, which was not exactly friendly with Houston’s queer community or its communities of color.

“I never saw Larry lose his temper,” Parker recalls. “He was always very passionate, but very controlled and focused. I don’t know how he internally processed the racism in our community, but he put it aside and did what he needed to do.”

Bagneris recalls developing a plan that first involved throwing his political support behind Judson Robinson Jr., a Black City Council member at the time. He knew that if he did so, Robinson would help get him an audience with the police chief. It worked, and the chief sent Bagneris and his friend Carol Finema to Assistant Chief Bankston, who was responsible for issuing parade permits.

“I asked Carol Finema to go with me to get this permit. We dressed in business attire, and we walked in. Back in 1978, police were at a level where most were ex-Ku Klux Klan members. They could see [our community] was building political clout,” Bagneris recalls.

During that meeting with Bagneris, Bankston used the N-word, as well as the pejoratives “wetback” and “queer.” Finema dug her nails into Bagneris’ leg during that conversation, but he was determined to get the permit in spite of the verbal abuse. Surprisingly, Bankston quickly agreed to the parade permit, but Bagneris needed more: a permit for a band, and another one for “female impersonators” (aka the drag-queen performers).

First, the band permit. “[Bankston said to me], ‘Oh, y’all will be blowing on instruments, not on each other? Okay, we will get permission for the band, too. Get out,’” recalls Bagneris.

But then Bankston balked at Bagneris’ drag-queen permit request, which was necessary since cross-dressing was illegal at the time. Bankston regaled the two with a speech about how “Houston was not San Francisco” and that the parade would need to live up to the “moral standards” of the community. Bagneris then rolled the dice and boldly pushed back by saying, “You do realize that some of these drag queens look better than most of the women you know, right?”

Amazingly, Bankston simply chuckled and replied “I am going to hold you to that on parade day.” The permits were granted, and the parade was going to happen in 1979.

Houston’s First Pride Parade

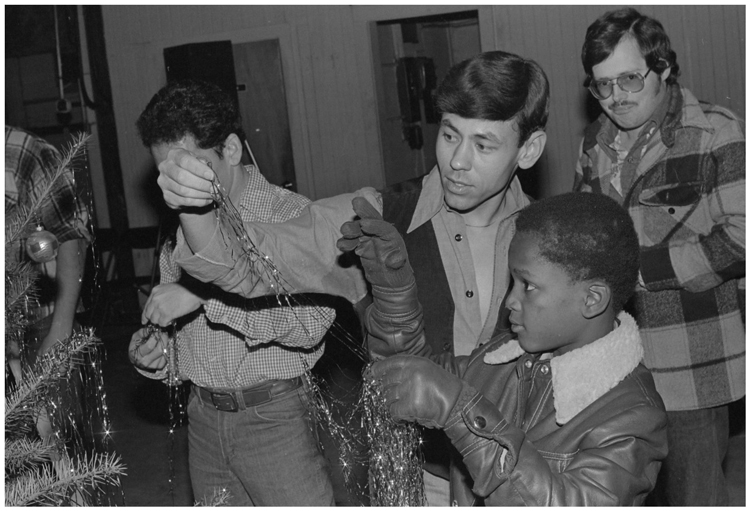

On the day of the parade, only two patrol cars were present. Bagneris recalls the pride he felt when he saw the impressive floats that had been created. Mary’s, a popular gay bar at the time, created a float with flowers and water pumping. There was a band to lead the parade, and “Disco Grandma,” a familiar personality at the gay bars, danced her way down the route.

“We had [a permit for only] one lane of Westheimer. I started moving the buses off the other lane, and we eventually took over the whole street. We realized we had about 10,000 people there, and we knew it was a success because that is about how many we had for the Anita Bryant march,” Bagneris says.

The parade finished at Spotts Park, where there was music, fireworks, and people getting registered to vote. They were allowed only nine minutes of fireworks, and Bagneris timed the music perfectly for that brief display, which (of course) ended with the ’70s gay anthem “We Are Family.”

“Larry always insisted we had to have fireworks,” Parker notes. “It wasn’t a celebration without fireworks, and the parade was a celebration.”

The Parade and Bagneris March On

Bagneris marvels at how Houston’s Pride parades have expanded over the years. “That first year, I was really the only one putting it together and getting permits. But as the years went on, it grew. More people got involved to help manage it. People commend me, but there were hundreds of volunteers.”

That growth was slowed in the 1980s as AIDS began to devastate the community. Parker cites the epidemic as the reason so many stories from those early Pride parades have been lost. “A number of gay male leaders died of AIDS, and their stories and impact went with them. I think Larry’s story got lost because he moved away, in part because of the trauma he experienced—that we all experienced—because of AIDS. I am glad that his story is finally getting told. I wish all of those lost stories could be told,” says Parker.

Bagneris ended his role in organizing the parades in 1986. His job began to require more travel, and the burden of losing so many people in the community to AIDS was traumatizing. He moved back to New Orleans with his partner, Jimmy Chavers Armstrong, who died in a car accident in 1990. Over the years, Bagneris has focused a lot of his time on fighting anti-LGBTQ legislation, including bills that discriminate against individuals with HIV. After flirting with the idea of entering politics, he ran for the New Orleans City Council a few years after returning home. Unfortunately, he did not win.

Bagneris still lives in the French Quarter (which he says is “the only place to be”), but he does manage to return to Houston every year for the Pride parade—that gift he gave to Houston’s LGBTQ community over 40 years ago.

For more info on the Charles Law Community Archive, visit houstonlibrary.org/gregory.

This article appears in the February 2022 edition of OutSmart magazine.