Houston’s Fight for Trans Equality

Repealing a harassment law after 119 years.

On June 22, 1980, according to the City of Houston’s Code of Ordinances at the time, I committed a crime.

What was the crime I committed that I fortunately didn’t get arrested for? I went to the Talent Night at Studio 13 in Montrose dressed as my true self.

It was the first time my then just-graduated-from-high-school teen self had been out of the house dressed en femme. But had the HPD vice squad raided Studio 13 that night, I would have been arrested and charged with a violation of Section 28.42-4 of the Code of Ordinances.

Section 28.42-4 prohibited a person from “appearing in public dressed with the intent to disguise his or her sex as that of the opposite sex.”

Translation: I would have been arrested for crossdressing.

That ordinance was passed in 1861, and had its roots in the wave of anti-crossdressing laws that got enacted back then. An 1848 Columbus, Ohio, law forbade a person from appearing in public “in a dress not belonging to his or her sex.” In the decade that followed, Houston and 40 other U.S. cities passed similar ordinances and laws, along with several states.

Those anti-crossdressing ordinances were used by police to enforce the gender binary. They were also used to harass our trans and gender-nonconforming siblings, as well as the gay and lesbian community.

The Houston ordinance was used to harass not only drag performers and trans people, but also butch lesbians. If you were a cisgender woman wearing fly-front jeans, you would be arrested by HPD vice officers for doing so. It’s why, for much of the ’70s, Houston department stores sold women’s and girls’ jeans with zippers on the hips.

HPD had been under the odious ten-year reign of police chief Herman Short since 1964. Short was a George Wallace supporter and an alleged Klan sympathizer who was reviled by Houston’s Black community. Short also turned his vice squad officers loose on Houston’s TBLGQ community, and their preferred method of harassment was the use of Section 28.42-4 to justify their raids on gay and lesbian bars.

If a drag queen was either not on stage or on their way to the dressing room when vice officers raided a club, they were arrested. When they raided Houston’s lesbian bars, they were targeting peeps wearing fly-front jeans.

In the Houston TBLGQ community, sentiment was growing to overturn the repressive anti-crossdressing ordinance, especially after trans woman Annette “Toni” Mayes was repeatedly harassed by HPD vice officers in 1972.

The 25-year-old Mayes was trying to adhere to the standard of the time for transitioning: living openly as the target gender for two years prior to gender-confirmation surgery.

Because 1970s fashion was blurring the lines between what was considered masculine and feminine clothing, crossdressing ordinances were under attack in the federal court system. Houston City Council, fearful that Section 28.42-4 would be overturned, decided to revise it in June 1972 with language outlawing anyone who appeared “on any public street, sidewalk, alley or public thoroughfare with the intent to disguise one’s gender as that of the opposite gender.”

Mayes eventually got tired of the constant HPD harassment, and in December 1972 filed a $200,000 federal lawsuit against HPD. The lawsuit made it all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Mayes unfortunately lost. While the lawsuit didn’t have the desired result of overturning Houston’s anti-crossdressing ordinance, it did get HPD to stop harassing Mayes until she had her January 1974 gender-confirmation surgery (GCS) in Galveston.

After Mayes’ successful surgery, she retired from the Houston trans-rights fight to focus on living her life. She passed away in November 2007, just weeks shy of her 60th birthday.

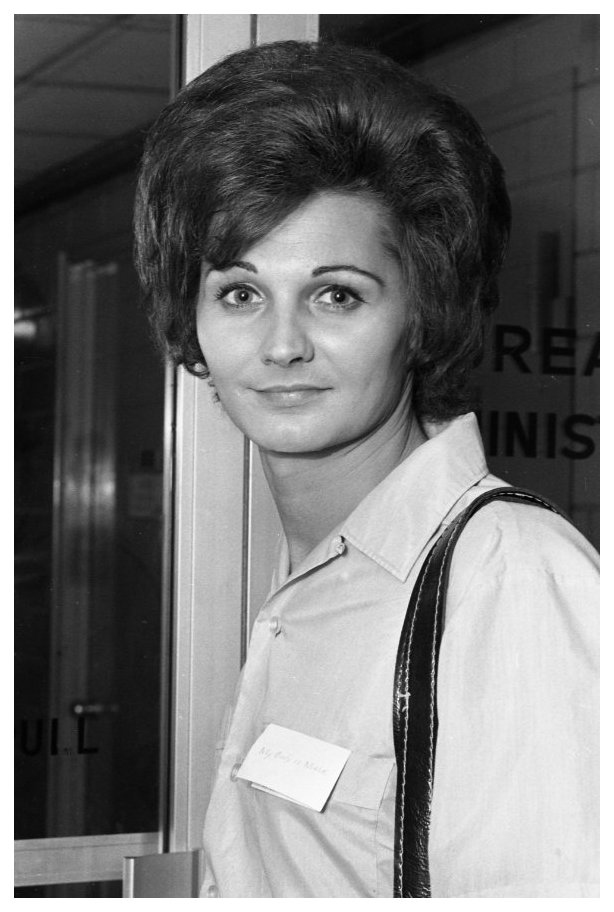

Phyllis Frye, a Texas A&M engineering grad, then entered the Houston trans rights picture as she began her transition in September 1976. Justifiably fearful that she would also be harassed and arrested by HPD like Mayes had been, Frye picked up where Mayes and the Tumblebugs had left off in the quest to kill the unjust anti-crossdressing ordinance.

For the next four years, Frye lobbied the Houston City Council and the man in charge of the HPD vice squad, HPD Deputy Chief Fred Bankston.

Another challenge to Frye’s efforts to overturn the unjust ordinance came when Mayor Fred Hofheinz, who was in favor of overturning it, was succeeded by Jim McConn in 1978. City Council was also expanded to 14 members by a federal mandate in 1979, with nine geographically based district seats being added to the five at-large seats.

Undaunted, Frye found City Council allies in Council Member Johnny Goyen (who told Frye in his office that he was not a fan of the mistreatment of Toni Mayes) and newly elected District B Council Member Ernest McGowen, who pushed council to repeal Section 28.42-4. McGowen also hired Frye as one of his City Council legislative aides.

In addition to the expansion of City Council, the repeal effort was aided in the spring of 1980 by two events: on April 3, federal district judge Norman Black ruled that the Houston crossdressing ordinance was unconstitutional, and Council Member John Goodner made a transphobic remark about Frye during a City Council meeting that prompted several Council members to privately meet with Goodner and call him out for it. Frye had been a volunteer in Goyen’s office until McGowen hired her, so at this point she was well-known and liked by many of the City Council members. Council Member Lance Lalor suggested the path to an apology: Goodner would move to repeal the crossdressing ordinance, with Lalor seconding it.

A repeal ordinance was prepared, and after several council-member tags delayed it, on August 5, 1980, it came up for a final City Council vote. The timing was fortuitous, because conservative Mayor Jim McConn was out of town, along with Council Member Jim Westmoreland.

During that fateful City Council meeting, Mayor Pro-Tem Goyen was handed the repeal ordinance by longtime City Secretary Anna Russell, and he immediately called for a vote. Council Members Homer Ford and Larry McKaskle were busy on their phones and unaware that the repeal ordinance was up for a vote. Under Council rules, a failure to vote is considered to be a Yes vote. With Council Member Christin Hartung casting the only No vote, Houston’s anti-crossdressing ordinance was repealed by a 9-to-1 vote.

We are now 40 years post-repeal, and it was a major step forward for our Houston TBLGQ community. It allowed us trans peeps the ability to visibly and unapologetically wander the 600-plus square miles of our city and not worry about being arrested by HPD for simply being dressed in clothing matching our gender presentation.

It also stopped the HPD vice squad from using the 1861 ordinance as a pretext for harassing the entire Houston TBLGQ community.

Oh, and one more thing: Phyllis Frye would make more trailblazing history in 2010 when she became a Houston municipal judge—in addition to being my mentor.

Monica Roberts is the founding editor of the GLAAD award-winning blog TransGriot.