New Houston Black LGBTQ Archive to Launch on Feb. 21

“I know we were there, but I can’t see us,” says founder Harrison Guy.

In June 2016, Houston activist Harrison Guy spoke at a Montrose Center rally marking the first anniversary of the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando. After the event, he was approached by a rally participant who asked if he had ever heard of Charles Law. Guy said he only knew what he had seen about Law in the Houston LGBT History Banner Project.

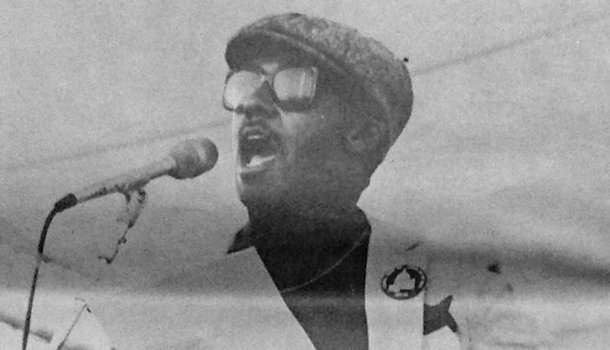

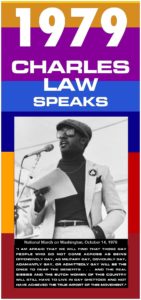

The person gave Guy a link to Charles Law’s speech at the 1979 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, which can be found on the massive Houston LGBT History website created by local historian J.D. Doyle.

Law’s speech resonated with Guy. “I could relate to his tenor and cadence, and I felt really connected to that speech. I started digging for more information about Law. I know about Stonewall and LGBTQ history, but this was about a gay black man in Houston in 1979,” Guy recalls.

Houston’s Invisible Black LGBTQ History

Although Guy found there wasn’t much material available to him, he felt that more history had to be out there. He started thinking of ways to unearth the legacy of Houston’s black LGBTQ community.

Although Guy found there wasn’t much material available to him, he felt that more history had to be out there. He started thinking of ways to unearth the legacy of Houston’s black LGBTQ community.

“I’ve looked at Houston’s LGBTQ history,” Guy says, “but I find myself asking, ‘Who is missing here?’” He looks forward to filling that gap.

Guy admits that all he’s known in the past about Houston’s black LGBTQ community was from meeting presentations or panel discussions. Nothing was permanently established and focused.

Guy asked the staff at Houston’s African American Library at the Gregory School about starting a black LGBTQ archive in Houston. What emerged from those early discussions is “The Black LGBTQ Houston History & Heritage Project—Charles Law Community Archive at the African American Library at the Gregory School” (or simply the Charles Law Community Archive). The archive will include activist papers, artifacts, and oral histories. Guy knows there are programs and posters and drag memorabilia out there that all need a home. “There is so much potential,” he says. “Even if it’s only three documents, it will be a start. We know LGBTQ blacks were there. But what were they doing?” Guy says. “The black community is very resilient, and we’ve learned to do incredible things. We rise to the occasion.”

Guy notes that many in the black LGBTQ community have felt the need to keep a low profile. “I expect this to be a challenge. It will not be easy,” he admits. “But I’m planting seeds and watching it grow. A Houston black LGBTQ archive just needs a start—and leadership.”

While searching Doyle’s online LGBT archive recently, Guy found the printed program from a 1982 banquet given by The Houston Committee, a black gay men’s professional organization active in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Charles Law was a founder of The Houston Committee, and some of the people listed in the banquet program were able to give Guy additional names to pursue.

Charles Law, the Inspiration

“Charles was active in both the LGBTQ community and the black community, just as I am,” Guy says, explaining the special bond he feels with a man he never met.

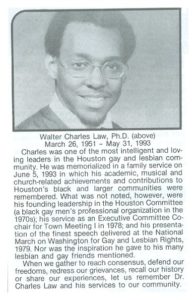

Walter Charles Law was born on March 26,1951. He earned a doctoral degree in education from Southern Illinois University and was employed at Texas Southern University, where he was appointed as the school’s archivist in 1977. By 1979, he had developed what would become the university’s permanent archive for official records, board-meeting minutes, presidential papers, yearbooks, dissertations, photographs, and other documents.

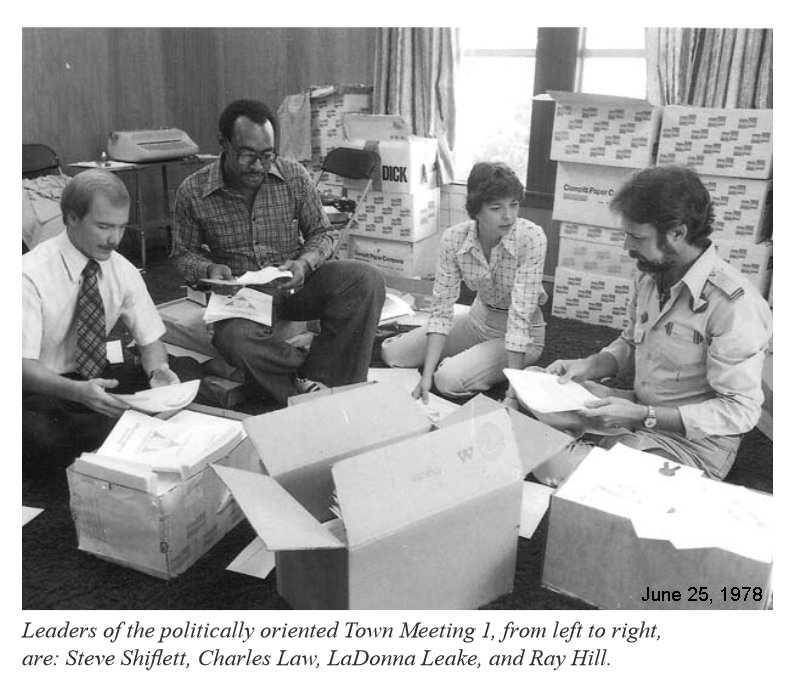

Law also helped organize (along with Houston’s pioneering gay activist, Ray Hill) the Town Meeting I event during Gay Pride week in 1978. Then in 1979, Law was invited to speak at the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. During the speech, Law said:

“I am afraid that we will find that those gay people who do not come across as being offensively gay, as militantly gay, obviously gay, adamantly gay, or admittedly gay will be the ones to reap the benefits . . .and the real sissies and the butch women of this country will still have to live in gay ghettos, and will not have achieved the true import of this movement.”

The printed program from the 1982 Houston Committee banquet features photos of the men most involved in the organization: Robert Carter, Ray Flournoy, Joseph Grant, Don Hood, Walter Richardson, Walter Tinson, Benjamin Barkley, Jimmy Rabb, Vincent Fuller, David Blackmon, Robert Qualls, Alfred Robinson, Burnett Edwards, and Terry Matthews. Law is also included in the program—perhaps the only Houstonian whose name is still recognizable by the larger LGBTQ community.

Dr. Law died on May 31, 1993.

New Archive to Launch

A formal launch of the new Charles Law Community Archive will be held at the African American Library at the Gregory School, 1300 Victor Street, on February 21 from 6 to 8 p.m., and the public is invited. An introductory program will be held on the second floor, and will be followed by a reception in the first-floor lobby.

The new archive has already made one important acquisition—a wheelchair owned by Chase Bank (formerly Texas Commerce Bank) that was used exclusively by the late congresswoman Barbara Jordan during her trips to Houston in the 1970s and ’80s, when she served on the board of directors for Texas Commerce Bank. For several years, Jordan depended on that wheelchair whenever she flew in from Washington DC for board meetings.

Staff members at the African American Library at Gregory School are pleased to see the Charles Law Community Archive become a part of their collection. Danielle Burns Wilson, manager and curator, says, “The mission of the library is to preserve and promote Houston’s African-American history and culture. We are long overdue in celebrating and preserving the history and contributions of the black LGBTQI+ community in our city. We see the Charles Law Community Archive as just one small step toward telling a more representative story of not only black Houston, but of the city as a whole.”

Miguell Ceasar, the library’s assistant manager and lead archivist, notes that people often think of an archive as just a place to read about historic firsts or extraordinary events. “While we celebrate those histories, too, at the end of the day the library is truly a community archive. One day, researchers are going to come here looking to do research on Houston’s black LGBT community, and because the Charles Law collection was created, they will be able to successfully find materials that document this important history.”

Erika Thompson, the community liaison for the library, believes that maintaining a community archive is a form of activism. “When we think about mobilizing for a common cause and fighting for rights and the recognition of one’s humanity, not only do we find these rooted in the histories of the African Diaspora, we find it in the histories of all marginalized groups. The role of an archive, then, is not only to chronicle what was, but also to inform the next generation of fighters, scholars, and activists as they ready their own paths toward actualization.”

Lorin Roberts, president of Pride Houston, Inc., reflects on the new LGBTQ archive: “Black people have been the afterthought and treated as off-brand Americans systemically in our country’s history. To be black, a woman, and part of the LGBTQIA spectrum, I can say I have felt what it is like to be considered an afterthought and invisible by mainstream society. Reflecting on my own childhood and living in this world as an “other,” it was—and is to this day—monumentally life-changing to see people in society who look like me making waves of positive social change. It gives every one of us who has felt like an “other” a feeling of empowerment, and lets us know that we, too, can make a change. We, too, can be more than what society thinks of us. [Learning our history lets us know] that we, too, matter. The Charles Law Community Archive will be important to those who have felt invisible, because it marks a space in our public sphere that proves we, as people of color, are agents of positive social change who have history on our side.”

Guy works in the finance department at the University of Houston central campus. This year he is celebrating 25 years as an “out and proud” gay black man. He got his start in community activism at the Donald R. Watkins Memorial Foundation, an HIV/AIDS outreach organization focused on testing and medical care for gay black men. He is currently chairman of Mayor Turner’s LGBTQ Advisory Board, and a member of the Houston GLBT Political Caucus. He has served on the Democratic National Committee’s LGBT Advisory Board, and on the diversity committee for Pride Houston, Inc. Guy is married to Adrian Homer-Guy.

Guy welcomes any information or materials about Houston’s black LGBTQ history, and hopes to grow the collection to a point where an exhibit can be mounted during a future Black History Month. He can be reached at mrharrisonguy@gmail.com.

Listen to Law’s speech at the 1979 National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights here.