Talking Shakespeare

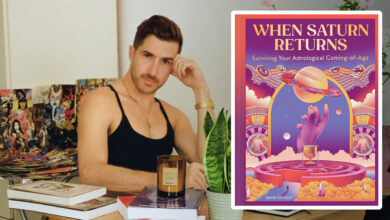

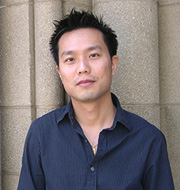

Novelist/filmmaker Samuel Park brings the Bard to page and screen. SPECIAL WEB EDITION – EXTRA CONTENT

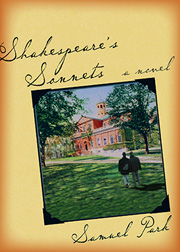

Some people like to read, some people like to watch movies and some people like to do both. Gay novelist and filmmaker Samuel Park has those bases covered. Shakespeare’s Sonnets is the title of his recently published novel from Alyson Books and his short movie, which is part of Boy Briefs 3: Between the Boys—8 Gay Short Films About Hooking Up, the Picture This compilation. However you choose to partake in Shakespeare’s Sonnets— a story set at Harvard in the 1940s dealing with both the mysterious love object of the sonnets as well as the unfriendly climate for homosexuals on campus, and the budding relationship between male students Adam and Jean—it is well worthwhile.

Gregg Shapiro: How long have you been teaching at Columbia College in Chicago?

Samuel Park: I just started. I was just hired in September [2006]. I’ve been teaching the drama courses in the literature department. Shakespeare, American drama, multicultural drama. I’m the Drama Queen. I get a lot of theater majors and from other departments [such as] film and video.

Where were you prior to Chicago?

I was at USC, getting my Ph.D. in English Lit and writing fiction. I still go back and forth between LA and Chicago.

In the tradition of the “which came first” question, which did come first in terms of Shakespeare’s Sonnets —the movie or the novel?

The short film came right before the novel. I made the short film, and then I wrote the novel, but they both came out at the same time, just because it took me so long to finish the short film.

So the actual genesis of the piece can be traced back to the screenplay?

It actually started out as a play. [Laughs] I believe in recycling. Recycling is important. These raw materials such as creativity must not be wasted. [Laughs] I’ve written a lot of things, but this is one of the few things that people have really been interested in. People kept asking me to come back to it. After I wrote the play, a friend said that it would be a great script. I wrote it as a screenplay, and then I made the short film with Vincent [Kartheiser]. I met with the [production] people from Latter Days, and things were going along well, and then things fell apart and it didn’t happen. But out of that came the book. I’m very stubborn, and I felt like if I’m not going to get a movie out of this, I’m going to get a novel. I feel like the characters need to breathe and be alive somehow. This is my way of rescuing them.

Is there any chance that down the line there will be a full-length feature made?

I hope so. The production guy’s former assistant, who is kind of moving up the ladder, has been trying to send it around. It’s a weird beast because you have to get it into the hands of the right person.

Would you want to direct it, as you directed the short film version?

I used to, but now I don’t want to anymore because I feel like it would hurt its chances of getting made. I want someone who’s got a little more leverage to make it.

As a reader, the book felt like it had two primary themes—the first being, of course, Shakespeare. Can you please say something about your interest in Shakespeare?

For the purposes of the book, [Shakespeare’s] sexuality…I’ve always been interested in the idea of recovering a historical past that’s been  lost to us. The straight critics get very defensive about Shakespeare, saying there’s no proof, there’s no evidence. There’s also not that much proof or evidence that he was straight, either. So I objected to [his being] “straight until proven guilty.”

lost to us. The straight critics get very defensive about Shakespeare, saying there’s no proof, there’s no evidence. There’s also not that much proof or evidence that he was straight, either. So I objected to [his being] “straight until proven guilty.”

Why not the other way around?

Exactly! People say he was married and had three children, but there are a lot of people who were married and have children [and are gay], especially in our culture. I want children. Shakespeare didn’t have the option of getting a Chinese baby. I don’t think that means anything. I loved the idea of looking at the past and finding the queerness of people that we had assumed to be straight.

As one might expect, the sonnets figure prominently into the novel, but are there sonnets on which the novel or the characters are directly based?

Yes. The overall arc of the sonnets is followed by the book. What happens in the sonnets is that you have the poet romancing this young man, and then later, in the last third of the sonnets, this woman, the Dark Lady, comes between them because she starts sleeping with the young man, which brings out all sorts of jealousies in the poet/narrator. In the novel, it has the same sort of triangulated love structure—except that the Dark Lady is played by Professor Mullins. I thought that it would be cool to have a man play the role. The overall arc is very similar to the sonnets, but with a more contemporary, gay twist.

In the last few years some non-fiction books have been published about the Harvard homo purge, so there continues to be interest in the subject, which is the second predominant theme in your novel.

There’s a book that just came out, whose name escapes me, which came out after I wrote the novel, based on an article that was published in the Harvard Crimson about the scandal in the 1920 when a student committed suicide. And when they dug up the background on the suicide, they found out that he was part of this group of students who were accused of being gay. They were essentially persecuted and being expelled from school. They were part of these out students who would throw parties and have sex with each other. So there was this sort of gay sub-culture at Harvard.

The novel isn’t based on that, because I wrote it before that article came out, but I suspected that if you have a homo-social environment with all those young men, and you’re gay, you would have that kind of sub-culture—especially at Harvard, a place of privilege, where you can somehow bend the rules. It’s a completely self-enclosed world, with its own set of rules and it’s also a kind of homoerotic world where you always show your affection towards each other. You’re away from women. It’s like a recipe for a porno. [Laughs]

Something else that was striking about the novel is that the style of language felt true and appropriate to the era.

I’m so glad that you noticed that, because I don’t think anybody else did. [Laughs]

One of the stories that I find most fascinating is E.M. Forster’s Maurice, which he wrote in 1912 but didn’t come out until 1971. I was imagining, what if there was another Maurice that we didn’t know about? I was fascinated by that idea, but also by taking something from the past, but imbuing it with our own sensibility. The book does have sex in it. It’s a little racy, and it’s got all these gay parties. I liked the idea of it being a found object that has our own freedom, in terms of describing our sexuality. I did this in the short film, too. I tried to make it look like a `40s movie. That’s the idea behind the book, too, to borrow that kind of language.

Is there any of Samuel in either Adam or Jean?

I think there is zero of me in Adam, which is why he was the hardest character to write. I’ve never been closeted or afraid to express myself. I had the hardest time imagining what somebody like him would think or feel. Then I realized that he’s not really that closeted. He does have sex with men.

But he has the freedom to close that closet door at his leisure.

Yes. The problem with Adam, I realized, is not that he’s closeted, because he’s not. It’s that he’s selfish. So I had to tap into my own selfishness and my hanging on to whatever little privileges that I’ve had, and not being willing to sacrifice. I think that’s what his arc is—learning how to sacrifice. I’m very much like Jean in the sense that I’ve always been kind of a [pauses] —not anymore because I’m going through a very melancholy moment in my life [smiles] —but I’ve always been that kind of funny, silly Oscar Wilde type…the things that he says in the novel are things that I’ve said to my friends. I’m also like Mullins, too, because I’m so full of bitterness. [Laughs]You’re too young to be bitter.

I’ve been bitter since I was 13. [Laughs] But that fear that life has passed you by, which is something that I feel everyday. I think that the problem with Mullins is that he thinks that everyone is having much more fun than he is and he’s been left behind. I think we all can feel that way sometimes. That’s why I feel sympathy for him. I don’t judge him.

As someone who is a filmmaker and a novelist, if you had to choose one over the other, is there one about which you feel stronger?

That’s good question. I feel like it’s about what you’re doing at that moment. It’s more about time then about other inclinations about what you are doing that particular month or week. For example, this week I’m all about departmental meetings and being a teacher. But over the summer, I’m going to be all about my next novel. And I’ll probably have meetings with a few of my production people acquaintances, and probably have a week or two when I’m only the filmmaker. To me, it’s more like an appointment-based identity.

I stole that concept from a best-selling novelist friend of mine. Somebody asked her what it was like to be famous, and she said, “I’m famous by appointment. When I’m doing a reading, I’m famous. But once I leave and I’m with my boyfriend, I’m just whoever. I feel like all those different roles are appointment based. [Smiles]

Gregg Shapiro writes frequently about the arts for OutSmart.