Erasing Color, Erasing Community: Houston’s Rainbow Crosswalks and the Fight for Visibility

Houstonians reflect on what these symbols mean for safety and visibility.

When Houston’s rainbow crosswalks were first painted in Montrose, they weren’t designed as a political statement. They were built as a promise of safety, remembrance, and belonging. The intersection where they now lie is where Alex Hill was struck and killed in 2016. What began as a memorial grew into a beloved marker of LGBTQ+ visibility, safety, and pride within Houston and Harris County.

“Houston’s Pride crosswalk was created as a memorial to Alex Hill, who was struck and killed at that intersection,” community member Charles Swan shares in a moving Facebook post. “It was not a political stunt. It was a tribute—a reminder of a life lost, a symbol of safety, and a celebration of community.”

That symbol, however, is now under attack. In early October, Texas Governor Greg Abbott ordered the removal of the rainbow crosswalks, claiming it was a matter of “safety and consistency.” However, Houstonians like Abbie Kamin, Houston City Council Member for District C, argue that the move is neither grounded in policy nor rooted in concern for public safety.

“A private organization funded the painting to create not only a symbol for the neighborhood and the community, but a safety feature for the community to create a high-visibility crosswalk,” remembers Kamin. “The governor’s hiding behind this preposterous statement that this is for safety. No, the crosswalk was put there for safety.”

These rainbow crosswalks were never simply decoration. Their design actually improves pedestrian visibility and aligns with ADA accessibility principles, allowing them to function as a safety measure, a memorial, and a symbol of inclusion. In fact, all colorfully designed crosswalks—not just the rainbow ones—can be recognized as promoting inclusive mobility design. In this sense, they are “universal access crosswalks” and tools for visibility and accessibility.

That dual role of visibility and safety isn’t lost on Avery Belyeu, CEO of The Montrose Center, who sees the issue as both personal and historically grounded. “Our crosswalk has a unique history, and I think that a lot of people in the community remember that and have that emotional attachment,” she explains. “To see us represented in city infrastructure is a way for our community to know and understand that our city values us as residents.”

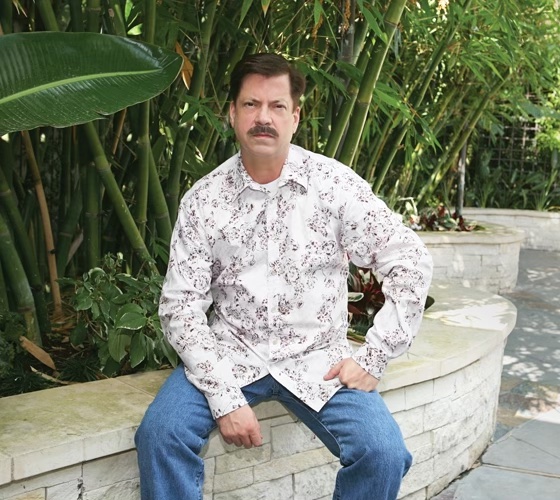

Jack Valinski, former Community Liaison for the City of Houston’s Department of Neighborhoods (DON) and current president of the Neartown/Montrose Super Neighborhood, sees Abbott’s directive as part of a growing trend of political erasure. “The fact that they’re removing books from libraries and schools, they are not allowing GLBT clubs in schools or colleges, they’re not allowing courses to be taught in public colleges, is really a bigger issue,” he says. “This rainbow crossing may be a small part, but this is an issue that represents the community.”

Belyeu, who is a trans woman, emphasizes that the crosswalk fight is part of the broader struggle against LGBTQ+ erasure, including ongoing legislative attacks on transgender Texans. “I believe our community is at its strongest when we link arms together and we are united in our fight,” she states. “The reality is that the fight is coming from many different angles. Today, the fight is the crosswalk. This last legislative session we had two bad bills that passed—one that impacts the ability of our youth to be represented and safe in schools, and another that is a direct attack on the transgender community and our ability to thrive in public spaces across this city and this state. It’s not either-or; it’s both-and.”

That layered fight against physical erasure and political silencing is why so many view Abbott’s order as both personal and ideological. “The fact that we have this one little symbol, and this bothers the governor so much that it has to be erased, is pretty sad,” Valinski added.

Charles Armstrong, owner of JR’s Bar & Grill and South Beach, echoed that sentiment. “It’s empowering, it’s validation, it’s community,” Armstrong says. “It’s an accomplishment, but I think it’s going to be short-lived.”

Armstrong believes the attacks are part of a broader conservative strategy of cultural erasure. “DeSantis rolled this out in Florida, destroying crosswalks to poke the gays with a stick,” he notes. “We’re going to erase anything that you’ve done. You see that with the African-American community and this administration erasing things from the National Museum of African American History and Culture and from textbooks, so children never see anything about slavery.”

Even as Armstrong expresses fears about the power structures driving such decisions, he remains defiant. “It doesn’t mean activists stand down,” he declares. “Fight the good fight. I fought it for most of my life. Never give up. Scream and shout if you have to.”

That spirit of resilience defines Montrose. “The data, in fact, shows that there have not been any incidents in that crosswalk since it was painted with a rainbow,” Belyeu points out. “So there is a strong case to be made that a high-visibility crosswalk, like a rainbow, is in fact something that keeps us safer. But at the end of the day, this isn’t about whether or not a crosswalk meets certain safety standards. It’s about an attack on our LGBTQ+ community.”

Belyeu and her colleagues at The Montrose Center are already organizing. “The Montrose Center convenes a coalition of over 22 LGBTQ+ community organizations,” she explains. “One of the things we’ve done after we understood that this was going to be a fight that was on our hands was to begin strategizing.”

Swan’s post echoes that enduring hope. “The paint may fade, but the message behind those colors will not,” he writes. “Pride has never been about crosswalks. It’s about walking freely—and that’s something no governor can take away.”