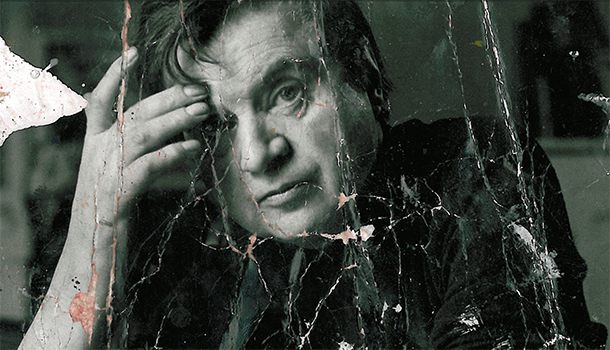

A Troubled Genius

MFAH showcases Francis Bacon’s beautiful and brooding paintings.

The summer of 2019’s Stonewall 50 observance caused galleries and museums around the world to turn the volume up on their usual gay content. I made it my mission to see as many of these exhibitions as I could. Arriving in London on my way to install my own Texas Queers show at The Horsehed (a wild alternative arts space outside of Manchester), I knew I had to get to Kiss My Genders at the Haywood Gallery on the Thames. That show was excellent, but all of my most plugged-in queer arts friends said the best Stonewall show was the Gagosian’s commercial gallery exhibit of Francis Bacon’s paintings, teasingly titled Couplings. I knew well that Bacon was gay, fairly out (even in the 1950s), and a brilliant, challenging painter. In fact, he was the painter I loved most as a teenager. I had a framed poster for one of his NYC Marlborough Gallery shows in my ’70s teenage bedroom, well before I could articulate his dystopic brilliance. But Bacon for Pride?

Bacon’s romantic biography is violent and tragic, at least as negative as the very heterosexual womanizer Picasso (who is currently demonized by a generation of young art historians due to his treatment of the women in his life). But loving Picasso seems like an easy experience compared to a drunken, naked tussle with Bacon. Take Peter Lacy, the fighter pilot who Bacon claimed was the love of his life. He drank himself to death in Tangiers, after having beaten up Bacon on multiple occasions (which Bacon apparently enjoyed, and claimed deepened his ardour for Lacy).

Then in the Bacon biopic Love Is the Devil, we see the gorgeous Daniel Craig playing George Dyer, Bacon’s muse and lover who committed suicide on the night of Bacon’s retrospective opening in Paris. (The idea that Dyer was back at his hotel dying as Bacon was being feted has been proved false—he had died two days earlier; Bacon just kept it a secret.) Yet Bacon’s efforts to make that dramatic tale burn bright were successful for a few decades. But you can’t blame either the cinematic or the real Dyer for feeling desperate. Knowing how many gay men endure unending trauma with their alcoholic relationships, seeing a Bacon exhibition aimed at elevating our sense of gay pride seemed an awkward fit, at best.

Yet, when I walked in to the Gagosian exhibit, I understood my friends’ wild enthusiasm. In 1955, Bacon created and exhibited a painting of two men having sex with an animal power, reminding us that every time we commit sodomy we have the potential to connect with a dark, animalistic queer spirit. When that power takes over our bodies and souls, we connect to Bacchanalian rites going back to time immemorial. While Bacon did not return to the theme of entwined male bodies until the mid-1960s (after English sodomy laws were struck down), his masculine world remains intoxicatingly erotic 50 years later.

Any gay art lover who doesn’t get to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, this spring to see the exhibit Francis Bacon: Late Paintings deserves to lose their gay card and never have passionate sex again. These works are not for those with delicate sensitivities. They are as harsh as they are beautiful. An updated version of an exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Houston show starts with a late-1960s portrait of Bacon’s lover George Dyer. (Bacon promoted another questionable story that the two met when Dyer was burglarizing Bacon’s home, also seen in the biopic.) Dyer’s link to crime, even if he was not good at it, gives a sense of what Bacon found compelling in a lover.

MFAH curator Alison de Lima Green, a beloved Houston treasure, points to the outpouring of Bacon’s best work in response to the trauma surrounding Dyer as a way to understand Bacon’s heartbreaking genius and the explicit memorializing seen in the huge triptych In Memory of George Dyer, 1971. The paintings will make viewers wonder how Bacon could go on for another twenty years. Anyone who has lost a loved one to suicide will see the triptych’s central panel with the figure opening a staircase door and wonder, “Could anyone have prevented this?”

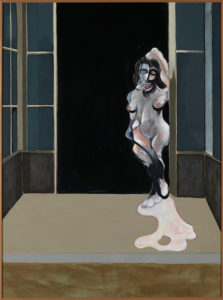

Unlike most Bacon museum surveys, the MFAH show will start in the year of Dyer’s suicide when Bacon is already one of the most successful artists the world had known. He could have just coasted by repeating himself, but these paintings from his last two decades are typified by startling formal experiment. The palette of some of the works in the MFAH exhibit will surprise those who know Bacon as the brooding master of dark fury. While the working-class, rough-trade lads he most desired are less visible than in other shows, Bacon’s deep engagement with the art of painting—and the masters of the form, from Velasquez to Picasso—is highly evident. Bacon even went outside of his comfort zone to try his hand at the female nude, and therby wrestle with Picasso’s overwhelming genius. Bacon’s recently rediscovered final work, Study of a Bull, 1991, has a startling clarity and challenges Picasso’s ownership of the bull motif in painting.

The final romantic relationship in Bacon’s long life is visible in a 1991 triptych in which José Capelo, a Spanish banker 40 years younger than Bacon, is shown on the left panel while Bacon’s face is acres away on the far right. Bacon was smitten enough to give Capelo a number of his paintings, in addition to a large sum of money.

Capelo ended up in the newspapers again when those paintings were stolen from his Madrid apartment, but then recovered. Although Capelo denies that “lovers” is the right term for their relationship, it appears to have been a mainly positive relationship when compared to the violently drunken lovers Bacon had in his earlier life. Alison de Lima Green is happy that this Capelo triptych (from New York’s Museum of Modern Art) will be in Houston. “Bacon really was a romantic. He flew to Spain to see Capelo against doctor’s orders.”

Bacon’s genius (as well as his love life, in all its erotic, dark frenzy) will be on view at MFAH from February 23 through May 25. I am recommending the show as a first-date destination for all of my most complicated single gay friends. If their dates can handle these paintings, they can handle my friends!

What: Francis Bacon: Late Paintings

When: February 23–May 25

Where: Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Info: mfah.org

This article appears in the January 2020 edition of OutSmart magazine.

FB Comments