Gay through the Ages

LGBT history is as old as dirt

LGBT history is as old as dirt

by Kit van Cleave

During Gay Pride celebrations, Americans of all persuasions often remember the movement’s antecedents, pointing with pride at celebrities like Sappho, Michelangelo, Oscar Wilde, Montaigne, Walt Whitman, Andre Gide, E.M. Forster, Radclyffe Hall, Christopher Isherwood, Sergei Diaghilev, and Nijinsky.

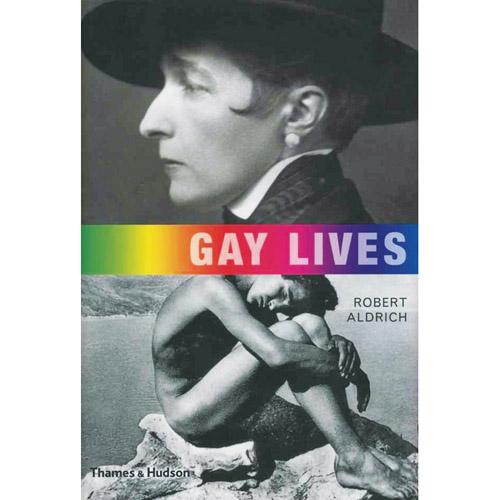

They’re all here in Robert Aldrich’s surprising book, Gay Lives, hot off the presses in time for this annual rite of freedom and tolerance. Aldrich has made a major contribution by including so many gay geniuses, artists, inventors, and leaders many readers will find out about for the first time.

He has also made an effort to embrace lives outside Europe and the West, such as an Arabic painter, Sri Lankan and Japanese photographers, a South African activist, a Jamaican novelist, and a Vietnamese poet.

Aldrich starts by defining terms—an important emphasis for historians of gay culture. “Homosexuality,” he points out, was a word created in the 19th century. Prior to that, the discussion ranged from pederasty in ancient Greece, “spiritual friendships” in the medieval period, “humanistic friendships” in Montaigne’s time, ambisexual artists in the Renaissance, through to “women-centered relationships,” “the third sex,” and “urnings” in the latter 19th century.

The book begins with the shared tomb of Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum in the year 2400 BCE, whose names meant “joined to life” and “joined to the blessed state of the dead.” Their double entombment and the hieroglyphs in the tomb indicate attitudes more appropriate to husband and wife—most unusual at the time. David and Jonathan (11 BCE), Sappho (612 BCE), and Socrates (469-399 BCE) are joined by Roman emperor Hadrian (76-138 CE) and his lover Antinous (110-130 CE) in the book’s discussion of true love.

In many countries in this era, it was quite legal for an older man (erastes) to play an active role with a younger (eromenos) passive youth. Sometimes these initiates were called ephebe, and were adolescents from a suitable social class. The older partner was bound to mentor and provide for his ephebe.

Aldrich enables his readers to follow this pattern of sexual development in various societies. Chen Weisong (1625–1682), appointed to the civil service under China’s Emperor Kangxi, was assigned to write a history of the Ming Dynasty, when same-sex relationships were commonplace. Ten or more of the ancient Han Dynasty emperors openly indulged with same-sex lovers, and male brothels were frequent in Fujian.

Having a young male partner in the Ming and Qing periods indicated success and social standing for an older male. By 1860, some 35 male brothels existed in Tianjin, and only Mao Zedong’s communist revolution of 1949 finally put an end to Chinese imperial sexual traditions.

In the 4th century, saints Sergius and Bacchus were officers in the army of the Roman Emperor. “Being as one in the love of Christ,” as they wrote, they were accused of heresy; Sergius was tortured and beheaded, while Bacchus was flogged to death. Still, due to their miracles and historical significance, they were canonized saints by the Roman Catholic Church, as Catholic historian John Boswell pointed out in his Same-Sex Unions in Premodern Europe (1994). Aldrich holds this saintly pair up to “prove that Christianity has not always been as intolerant of same-sex relationships as it would appear.”

And that’s just the first few chapters.

A few others of note in Aldrich’s book include:

• Antonio Rocco (1586–1633), author of L’Alicibiade fanciullo a scola, the first academic dissertation on homosexuality in early modern Europe;

• Benedetta Carlini (1590–1661), the first lesbian nun with a willing lover in gay literature;

• Kathryn Philips (1631–1664), whose writings “showed the importance of women-centered affinities in life and letters”;

• Chevalier d’Eon (1728–1810), upfront aristocratic French transvestite;

• Edward Carpenter (1844–1929), author of The Intermediate Sex (1906), the first defense of homosexuality in England, who codified the word “urnings” to set gays apart from straights, and prove they were not criminals or diseased.

Generously illustrated with both four-color plates and black-and-white photographs (including the most beautiful portrait of Yukio Mishima I’ve ever seen), this is a fascinating addition to the community library.

It’s important—at a time when right-wing propaganda and vitriol often uses gay people (and blacks, Hispanics, women, Jews, and Asians) as political targets—to have at one’s elbow a book so academically well-researched and fervent in its passion about finding those who preceded us all. You’ll learn a lot from reading this one.

Kit van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Montrose. She has published in local, national, and international media.

FB Comments