A Body of Collaborative Work

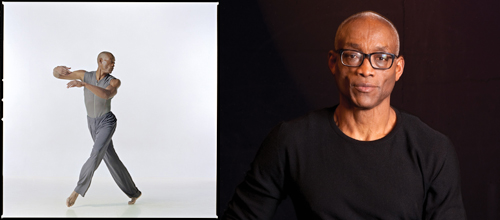

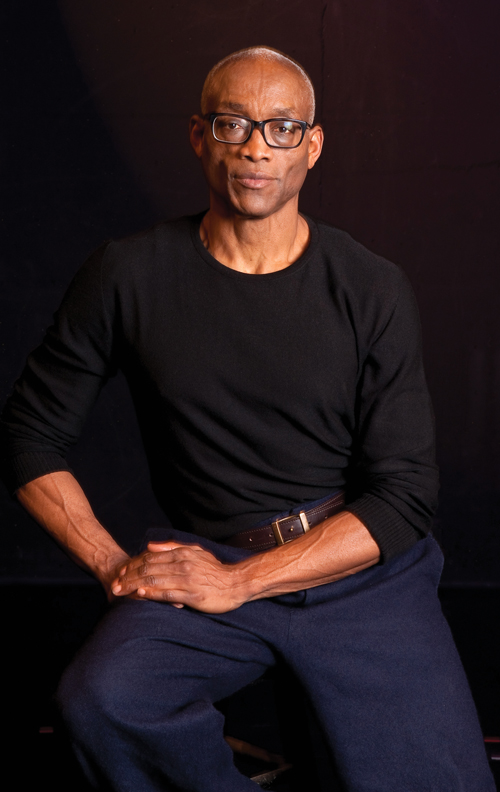

Bill T. Jones inaugurates a new lecture series at the University of Houston.

by Neil Ellis Orts

Photo by Stephanie Berger

Bill T. Jones has been making dances and collecting awards for a long time. His company, the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company, founded with his late partner in life and art, has toured the world with his particular brand of socially engaged dance theater.

He also has a history of collaborating with other artists, both within and without his dance company. This is the topic of the lecture he is giving this month at the University of Houston as he inaugurates the school’s Mitchell Artist Lecture Series.

Neil Ellis Orts: Can you give us a preview of what you’ll be talking about in your lecture?

Bill T. Jones: It’s going to be a far-reaching rumination, because I’ve done so much of this for so long, and lately everything I thought that I knew about it is beginning to shift. So I’d like to talk about what I understood it to be. I’ll give you one example—one story I’d like to tell.

Years ago, I worked with Max Roach, the great drummer, and Toni Morrison, the novelist. It was Max who brought me and Toni together. Toni had some reservations about “people dancing to words.” I remember Max told me a story about working with Toni. They were both invited to somewhere in California, to do an evening of drumming and reading. So on the plane—they’d never talked about it—he turned to her, she’s reading, and he said, “What are we going to do?” She said, “Well, you’re going to drum and I’m going to read,” and she went back to her book. That’s an example of one way of working together.

I remember someone was writing about the work that Toni, Max, and I had done, and they said it was more cooperation than collaboration. I don’t think I understood that distinction, but now I think I maybe do. [In a] collaboration, it seems that everyone must be a stake holder in an impulse or an idea. At least that’s how we’d like to think of it. It’s got to be among equals. I say that with some reservations because I’ve been working with my dancers for years, and some things they make. Some ideas they actually execute. I might get the idea, but they execute it, and I think we have to call that a collaboration as well. But I suppose the classic definition, even by my own estimation, would be: People from disparate disciplines coming together and going in pursuit of a result, and there’s a kind of conversation that goes on. Everybody brings to the table their strengths and shares with the others their shortcomings, and we find a way past it.

I imagine there are different levels of collaboration and cooperation. Most choreographers I watch or talk to tell me they adjust their ideas according to the dancers they have.

Oh yes, it’s true. Actually, that’s one of the most important things in my company right now, just understanding why we are still together as an organization. There are people there who could be my children, if not my grandchildren. To call them my colleagues stretches it, but in fact they are.

I’m very influenced by the work I did years ago with social therapy. In social therapy, the presumption is that a lot of modern problems we have are not so much classically Freudian or Jungian, but are, in fact, real problems in the world that have to do with our class, with our race, with our orientation that we have to negotiate all the time. Now in a group like my dance company, is that group called “family” or is it called something else? I insist it’s a community—a community, oftentimes, of disparate personalities, disparate people, training, who have placed all their goodwill and their abilities at the service of an idea. And it’s my understanding, being the director of the company, that I’m responsible for the idea. Is it my idea initially? Not necessarily, but it’s got to be developed around some sort of vision about that idea and its potential. And that is what the director and the ensemble’s relationship is.

Now, from moment to moment, sometimes I have proposed, say, a dance phrase, and others might have a contrary notion, and sometimes their ideas are better than mine. In that instance, they become collaborators if they propose something that gets us going in a direction that maybe I didn’t foresee. Of course, the buck stops with me. It will be my responsibility to determine how far that process goes.

But it’s a humbling process, actually, creating anything. One has to realize that one does not know everything, one can’t tell what the end result will be. And you want to listen for—some people will say, somewhat romantically, “The universe is talking.” There’s a young dancer over in the corner who is goofing around and doing something silly, but it is interesting. So you ask them, “Come out to the middle of the floor and do what you were just doing.” They’re suddenly shocked, they find out you were looking at them—now it’s suddenly serious. “I liked what you were doing there, could you teach us what you were doing?” Suddenly, that person is a new stake holder, that person is asked to be articulate and talk about why and how they’re doing what they’re doing. I think that’s good for the process.

You’ve often said you wish to participate in the world of ideas. To my mind, that suggests a conversation. I know you draw inspiration from texts of various sorts, but do you find a critical analysis of your work creates a conversation with you and your future work?

It gets in my head, that’s for sure. And I have to digest it somehow, and sometimes there’s something good that can be found there and sometimes it’s a distraction. It’s a case-by-case basis. I have a lot of respect for thoughtful people of all stripes and I don’t think we all agree, but I also think there’s something precious in the individual and their idea. When to listen to others is a case-by-case basis, and I think we can learn, but sometimes learning is painful.

To talk broadly of your work, you often respond to your personal history, your family history, the history of Civil Rights—what do you make of this current moment, and how is it affecting your current thinking? I’m thinking of things like the Supreme Court decision on the Voting Rights Act, the forward movement on marriage equality, the apparent backward movement on women’s health decisions, and the Trayvon Martin case.

One of the problems of middle age is that, if you’re an artist like myself who started out with very high expectations of their own rebellion… I have lived in a very turbulent period but I am not the first human being on the planet to do so. I am still trying to understand the relationship between what goes on inside of me and what goes on outside. That’s what made dance so attractive. There was something about the dancing body that became the place where the world and the psyche meet, and that’s very powerful. So yes, I think about those things a lot. I am oftentimes angry at what I see as a retrenchment. I was born in 1952—how old are you?

I was born in ’63.

So I guess you came of consciousness in the seventies. So I think we both grew up in a time when the news and headlines are reporting on a world that may or may not be what you are actually living. I grew up in a time with black people who had a memory of the Deep South that I, growing up in the north, did not have. My experience of Jim Crow and all came through my parents’ recalling. That didn’t make it any less real. I did grow up with the idea of free love. “Turn on, tune in, and drop out.” I was at Woodstock. By the same token, I knew what black rage was. I was trying to negotiate—even when I didn’t know what I meant by that—negotiate these polarities of being, and I still am trying. I’m trying to get past what I call the ennui of middle age. There’s a sudden feeling of “why bother” that settles over you that you’ve been at something so long, like trying to live a rigorous and uncompromising life, and when you look at some of the things you’ve just mentioned here, it either makes you want to go out and start throwing bombs or you have to find some way to reconcile that you honestly feel, that you are honestly doing, and that’s a project that never goes away for a sensitive person, being a artist or what have you. Trayvon Martin caught me off guard, because people were behaving as if this was new. It makes one feel a little cynical. Are we living on the same planet? And cynicism is an enemy, I think. I say it’s all right to be skeptical, but one must never be cynical.

Of course all that is very recent, and I’m sure you are working on things that have been in process for a while.

I am about to go into a rehearsal of a new musical called Super Fly.

Did you say Super Fly, as in the 1970s movie?

Yes, 1972, to be exact. On our topic here, I am trying to make something of significance, but it is an entertainment vehicle. As you know, Broadway is extremely collaborative, I’ve had to learn that it is not the same thing as walking into a dance studio with my dancers and saying, do this, do this, do this. It starts with producers and writers, and they’re concerned about the story. I can have some say on the story, but I’m not the final word on the story. Then there’s a musical director, and the musical director has his own imperative. Producers want it to sound a certain way, they want a certain type song—there’s a lot of things. It’s exciting because I think it’s going to be an interesting show, but it’s teaching me every day. Here I am in middle age trying to learn to work another way.

So that’s one thing that has me going right now. My company has just premiered a new The Rite of Spring. It’s actually a mediation on The Rite of Spring, made with Anne Bogart and her SITI Company. That was quite a learning experience about how two different organizations, two different artistic leaders, two different practices can come together. That’s been very exciting. My dancers got the opportunity to use their voices, to act in it. That’s very exciting about what will be the next step, how can I continue developing them in that regard.

A lot of what goes on with my dance company has to do with the culture of our dance company and how it’s going to continue to grow. Janet Wong, who was my rehearsal director, was elevated to associate artistic director, something our company has not had since Arnie Zane was alive. That’s made for a very interesting conversation as we try to find out how the two of us can be co-creators.

The next work that I make for the company is going to have a lot to do with a favorite topic of mine, which is memory. Memory, how it exists in a literary sense and how it exists in the body. So right now, it’s the commercial theater on the one hand, a deeper commitment to my company on the other.

What: The Mitchell Artist Lecture Series with Bill T. Jones

When: September 12, 7 p.m.

Where: University of Houston Moores Opera House, presented by the UH Cynthia Woods Mitchell Center for the Arts.

Details: uh.edu, free and open to the public.

Neil Ellis Orts is a frequent contributor to OutSmart. He blogs his own religious views at crumbsatthefeast.blogspot.com.

FB Comments