Wes Holloway’s Perfect Bodies

Local activist combats invisibility with his art.

If you regularly attend art events in Houston, you have probably seen Wes Holloway with his perpetually smiling face, often pink-colored hair, and his huge, technically advanced wheelchair. He is a community activist and organizer for Houston artists, disabled people, and (most crucially) the disabled artists and young people he teaches. His studio door at Sabine Street Studios is usually open (when he is not in intense art-production mode) and visitors often quiz him about his sexual and romantic life in ways that one would not normally do on a first encounter. That’s because the art in his studio makes it clear that this is an unguarded human being who wants to combat the invisibility of disabled sexuality.

Holloway’s work looks directly at what it means to be a sexual gay man in a wheelchair. He explains that because he has been under constant medical scrutiny since his late teens, he has very little sense of what is private and off-limits for questioning. And that is a very good thing for his art. Since we, as a culture, have a huge blind spot in terms of how differently abled bodies express sexuality (preferring to think that mental and physical desire are absent from their lives), Holloway is on a mission to make visible his life as a horny young queer fellow in Houston.

Photos reveal that Holloway was a dreamy young Texan before he lost the use of his body in a diving accident. He explains that since he was so young when he became disabled, he never for a second considered not pursuing his dreams to become an artist. When asked if his coming into art-making or coming out as a gay man came first, he explains that the two types of blossoming were wrapped up together.

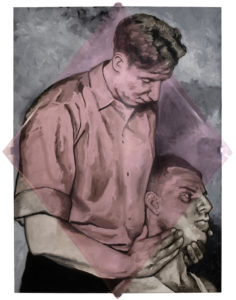

Stop the Bleeding (Facial Artery), 2019, oil and cellophane on canvas

The artist has regained enough use of his hands to paint and draw beautifully—with his somewhat wobbly and woozy painted lines giving his work an extra-seductive feeling.

It is impossible to visit his studio without being fully aware that Holloway likes to surround himself with collages, drawings, and paintings of intensely fleshy, naked men. Pondering the gay-male obsessions with the body beautiful, he muses, “As a man with a flawed body myself, I ask What is perfection? What is truly beautiful?”

His three-dimensional collage-based works will sometimes contain hidden, pornographic titillations mixed in with images of surgery and physical therapy (often deliberately confused, leaving inquisitive viewers to wonder if the hands we see are trying to get the subject off or are helping him walk). One of Holloway’s most moving pieces overlays his written musings about disability with movie star Christopher Reeves’ writings about his post-accident life with paralysis. Holloway’s larger paintings depict surgeries presented in a hyper-sexualized way, with one painting that shows how to stop bleeding in a way that looks like the moment before a first kiss. Holloway may skin a painting with a fragile veil of colored translucent plastic and let the skin fray with time—a metaphor for the intrusions his body requires to stay comfortable and healthy.

Differently abled queer folks have recently received a lot of attention in other forums—from the lesbian comedian Hannah Gadsby’s coming-out and being on the autism spectrum, to writer Ryan O’Connell’s Netflix series about trying to get laid and finding love with cerebral palsy, to Ryan Haddad’s one-man show Hi, Are You Single? that also explores sex and dating with cerebral palsy.

When asked about his dating life, Holloway’s usual smile grows bigger as he recalls his encounters with guys who are interested in getting to know him romantically. If they arrive with a list of requirements for what sex must be, they will likely be disappointed. But if they are willing to freely explore what their two particular bodies can do, everyone leaves satisfied and happy.

After all, any sex that is not at its heart exploratory and free-form might not be worth having.

This article appears in the August 2019 edition of OutSmart magazine.com.