Subtexts of Voguing

Photographs by Gerard H. Gaskin

2013 • Duke University Press Books (dukeupress.edu.com)

120 pages • $45

Hardcover

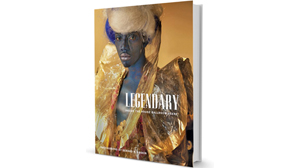

‘Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene’

by Kit van Cleave

Miley Cyrus did not invent twerking. Elvis Presley was not rock ’n’ roll’s sole pioneer. And Madonna was hardly the first to vogue. Many fail to realize just how much of our nation’s culture—fashion, dance, theater, film, music, literature, and language—is derived (or appropriated, as some would argue) from the African-American community. But yet, when white people copy these styles because they’re “so cool,” and propel them into mainstream culture, little credit is given to their African-American originators. This case occurs even more so when cultural identities intersect, like in the case of black LGBT folks.

“Voguing” was a booming part of black gay culture long before Madonna produced her iconic 1990 video. As Tim Lawrence points out in his introduction to Voguing and the House Ballroom Scene of New York City 1989–92, drag balls originated in the second half of the 19th century. By the time of the explosion of all the arts known as the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s, Langston Hughes reported that drag balls were the “strangest and gaudiest of all Harlem’s spectacles” in the black community. Hughes called them “spectacles of colour” and noted that they were attended by white celebrities. “Harlem was in vogue” and “the Negro was in vogue,” Hughes wrote.

In 1923, the New York legislature criminalized “homosexual solicitation,” but the drag ball organizers could still hold an event if a neighborhood group applied for police sponsorship on their behalf. In 1931, despite this tradition, police began to target the balls for soliciting. “If the cops have their way, the effeminate clan will hereafter confine its activities to the Village and Harlem,” Variety reported.

After World War II, gay soldiers returning from the battlefield started to settle in New York City. They quickly found fun and friendship competing in the drag balls; Ebony reported that in March 1953 some 3,000 contestants and spectators gathered in Harlem’s Rockland Palace to compete and watch.

“By the early 1960s, the drag ball culture began to fragment along racial lines,” Tim Lawrence reports. “The winners of these increasingly organized events tended to look white; competitors were expected to ‘lighten up’ their faces if they wanted to have a chance of winning the contests,” he writes. “So black queens started…their own events, with Marcel Christian staging what may have been the first (modern) black ball in 1962.”

Voguing, with text, photos, and interviews by Chantal Regnault, is the definitive book on this art of self-expression. It was published three years after Jennie Livingston’s 1990 documentary film Paris Is Burning gave the world an intimate look into the world of New York’s black ball scene, showing contestants “walking” in the balls, discussing “House” culture, and explaining lingo used within this community.

Twenty years after Voguing was published, photographer Gerard H. Gaskin brought us Legendary: Inside the House Ballroom Scene. It has little text, and is filled with amazing stills of ball champions, their “children” (younger ball participants), and spectators. In an essay detailing Gaskin’s work, Deborah Willis writes, “Storytelling is essential to ball culture, and reimagining new identities is an extension of this project.”

One of the main points of the balls was to offer a competition in which black gays could express themselves in any way they wished—presenting as the opposite gender, creating intricate fashion, and imitating celebrities’ glamour and fame—regardless of their situations in real life.

As Pepper LaBeija, “mother” of the House of LaBeija, put it in Paris Is Burning, “We prepare for a ball; a ball is our world, as close as we get to fame and fortune…walking [strutting] a ballroom floor is our fantasy of being a superstar, like the Oscars.”

Just as today, the streets were then the only recourse for young gay men orphaned by drug culture that left parents in prison or dead, or rejected by parents after coming out. In New York, many of these youths sneaked into the competition drag balls. The Legends (the champion competitors) saw an opportunity to help these kids, and the Houses gave them shelter.

What is a House? Says LaBeija in Paris Is Burning, “A House is a family, a group of human beings in a mutual bond…it’s a gay street gang,” but a street gang “gets its reward from street fighting, while a gay House streetfights at a ball by walking in the categories.” The “children” of the House needed “someone to fill the void [in their lives], as their real parents gave them such a hard way to go…these kids don’t have two of nothing,” LaBeija says. They would steal to get fabric for their costumes, and come to the balls hungry. There, for a few minutes, they could become anyone they wanted to be.

As the Legends began to age, they invited talented kids into their Houses, teaching them to design clothing, pose, and walk the dance floor as competitors. Multiple Houses formed, and after the House of LaBeija came the House of Xtravaganza, Ninja, Chanel, Pendavis, St. Laurent, and others. The kids, having no connection to real family, took the House names as their surnames.

As the ballroom scene grew larger, new categories developed; the younger folks wanted to compete in high fashion, winter sportswear, town & country, executive realness, butch queen, and military. Then two tough categories developed—realness, and face. Those in drag emphasized whether they could pass as “real” (whatever gender they were presenting as) on the street or in a job, like their straight counterparts. The beauty of one’s face and the attitude shown on it became primary to “give good face.” The balls were becoming big business and in the Livingston film, mainstream fashion, dance, and social commentators took notice; Gwen Verdon, Geoffrey Holder, and Fran Lebowitz are interviewed at the balls.

Gaskin’s Legendary photography shows the promenade, the walk, the costume, and dress. “Evening gowns, dress suits, top hats, and high heels are not gendered if worn with authenticity,” writes Willis. “Dandies” and “belles” vogued in styles from prior decades, emphasizing “the spectacle created by [the flair of] a group of people courageous enough to create their safe space.”

When Madonna did release “Vogue”, exposing this art form to mainstream pop culture, she cast many prominent ball competitors, most notably Luis and Jose Xtravaganza, as dancers in the accompanying music video. Although widely criticized for using people of color and gays as props to further her own career, Madonna does give homage to voguing’s origins by addressing the escapist aspect of the ball scene and how it allowed homeless gay youth to express their true selves in the song’s lyrics:

Look around; everywhere you turn is heartache.

It’s everywhere that you go.

You try everything you can to escape

The pain of life that you know.

When all else fails and you long to be

Something better than you are today,

I know a place where you can get away:

It’s called a dance floor, and here’s what it’s for, so

Come on, Vogue.

All you need is your own imagination,

So use it—that’s what it’s for.

Go inside for your finest inspiration;

Your dreams will open the door.

It makes no difference if you’re black or white,

If you’re a boy or a girl.

If the music’s pumping, it will give you new life.

You’re a superstar, yes, that’s what you are, you know it.

Legendary and Voguing demonstrate how, as in the Harlem Renaissance, an oppressed minority can, when freed from oppression, create beauty and magic through art. Both books are musts to have and share. Perhaps Houston’s gay community can begin its own renaissance of voguing balls?

Kit van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Montrose. She has published in local, national, and international media.