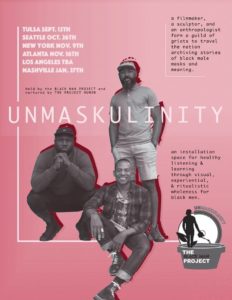

Unmasking Masculinity

Filmmaker Brian Ellison gets men talking about the pain of “toxic masculinity.”

Houston educator and filmmaker Brian Ellison decided he wanted to do more than just talk about toxic masculinity. The result is a trailblazing film entitled UnMASKulinity.

Ellison says his purpose was to introduce a new understanding of masculinity as a way to help men heal their emotional wounds. Originally intended for other African-American men, the film has proven to be a tool that anyone can utilize.

“It all started with my own personal insecurity,” Ellison says. “I grew up in an era when black masculinity was so fragile. Anything could challenge it. One misstep could take you out of the male pool permanently.”

As Ellison grew older and began to feel more secure in himself, he started having conversations about masculinity with friends. One day it struck him that what he had learned about being a man while growing up wasn’t logical. He began to question why black men are often forced to live in a restrictive box that limits their emotional range.

Getting Support for an Idea

Ellison, a heterosexual ally of the LGBTQ community, wanted more for his twins—a boy and a girl. He wondered what he could do to help children grow up free, and for men his age and older to recognize that limiting their emotions can make them sick.

Taking a big step, Ellison applied for an Ideas Fund grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation to produce a film. Winning that grant made Ellison feel validated that someone else believed in his idea enough to provide production funding for a film.

Looking back, Ellison laughs: “Now I had to do this thing!” He pulled together a creative team from his circle of friends and started interviewing African-American men. The men were asked to talk about their upbringing, and to recall what made them who they are. “The men began to realize their limited perspectives on masculinity and where they came from. There were a lot of ‘Aha’ moments,” Ellison says.

Although time and budget were limited, Ellison’s crew did what they could in five months. They determined that at least 28 interviews would have to be conducted in order to make it impactful. Ellison made sure the interviews were as diverse as possible. “Everyone’s story was important—young, old, queer, straight. We didn’t want anyone to feel [that the film didn’t speak to them].”

By late December of last year, a rough cut had been edited for a preview screening by 400 people at the Midtown Arts and Theater Center Houston (MATCH).

Masculinity from a New Angle

Ellison’s completed 50-minute film has its own sort of magic. Carefully edited, it moves at an even pace as its message unfolds. Ellison wants viewers to realize that all men can be strong and sensitive. The film has a gentle touch, with men talking calmly but confidently about their journey toward a new understanding of masculinity.

The film opens with a shot of Harrison Guy, Pride Houston’s 2019 Male Grand Marshal, against a warehouse background. Rose petals fall on him as music plays. Every ten minutes, a musical dream sequence occurs. In one, Guy is floating freely underwater. In another, a tap dancer performs a routine in a boxing ring. Ellison shows how masculinity can be a mixture of both brute strength and gentle creativity.

The cinematography is professionally done, but it’s also obvious that the film was made on a tight budget. This actually works in the film’s favor by allowing the interviews to come across as heartfelt and without pretense. The work is a labor of love.

The crew wanted the film to have a healing message. Ellison says, “We want people to walk away challenging old ideas and thinking of new ways to start processing. Viewers will come away with some, but not all, answers. What we give them is a platform to begin conversations that have never been there before.”

Ellison wants to take the film to schools, colleges, community centers, film festivals, and other venues where people are open to exploring the issue of toxic masculinity. The intent is to use the film to spark serious discussions after the screenings.

“Black men need a space to go to heal,” Ellison says. “Women have done a better job of healing and release. Men don’t always have to talk about sports—they need to talk about the stuff they think about [when they] can’t sleep—unresolved issues from fifteen years ago. They need to address the little boy inside them, who has never had a voice.”

While each interviewee has his own story to tell, there are also common threads that run through all of the interviews: vulnerability, self-love, and tears. “I never saw my father cry” is a refrain often heard during the interviews.

In one particularly moving segment, artist Michael Stevenson is asked to talk to himself as a 14-year-old boy. Brushing back tears, Stevenson delivers a poignant response.

The men also talk about black versus white masculinity. In the black environment, boys are taught to be hard because the world is going to be a tougher place for them than it is for white boys. Creative pursuits such as dance and art are looked down upon, with judgmental labels quick to follow. Therapy is looked on as the sign of a shameful mental illness, and not easily embraced. Boys are told to “man up,” which is code for ignoring their feelings and acting like everything is okay.

Even though Ellison played college football, he still had to come to terms with his nurturing nature. The film’s message is very personal to him, and led to some “Aha” moments of his own. Harrison Guy told him that it’s one thing to be gay, and another to be black and gay. When Ellison was growing up, the black barbershop was his refuge. But Guy never felt safe there, and it wasn’t a place he wanted to go. “I’d never thought about that,” Ellison admits.

The Impact of the Film

Guy explains why he decided to be a major part of the film: “Toxic masculinity in the wrong hands can be deadly to feminine men like me. This same toxicity in our own hands can cause us to be equally detrimental and deadly to ourselves. This film tackles a topic that is difficult for men to discuss, and it allows us [to be in a] space of vulnerability that is rare. I knew that my presence was necessary in order to serve as a reminder that conversations about men should include all spectrums of manhood.”

Another participant, Anthony Suber, says, “The path to self-discovery is paved by self-reflection. As an artist working in cultural- and societal-based themes, I believe in and directly connect to this film. The concept for this work is poignant and necessary during this period of cultural shift that we find ourselves party to. It was humbling being a part of something that has the potential to rewire culture and reframe how we think about manhood, masculinity, and how that applies to African-Americans.”

Anya Doula adds her words of praise for the film: “I went to the premiere with the intention to be open. The film [has a message of] raw truth told by the black men [who were interviewed]. The safe space that Ellison and his team created allowed a freedom of thought and a [vulnerability] that we rarely see from black men on film. We do not see or hear these conversations from black men anywhere in the mainstream.”

Anya Doula adds her words of praise for the film: “I went to the premiere with the intention to be open. The film [has a message of] raw truth told by the black men [who were interviewed]. The safe space that Ellison and his team created allowed a freedom of thought and a [vulnerability] that we rarely see from black men on film. We do not see or hear these conversations from black men anywhere in the mainstream.”

Josie Pickens adds her thoughts: “Brian Ellison’s gorgeous and timely film reminds us to be gentler with black men, who are constantly fighting a battle to find their place and value in a system of unhealthy masculinity that leaves many of them trapped inside a performance they would like to escape. UnMASKulinity left me with more questions than answers, which is why it’s such a radical and valuable piece of work.”

Expanding the Film’s Reach

Earlier this year, Ellison received a John S. Kellett Foundation grant to expand the film’s reach with additional interviews. There are also plans to create a study guide to accompany the film that will help audiences process their thoughts. “This grant opens up opportunities to take this outside of Houston,” Ellison says.

The film still needs additional financing, and a GoFundMe page is available for people who would like to help. Ellison also welcomes the opportunity to screen his film in local venues.

Ellison was heavily influenced by filmmaker Spike Lee while growing up. Years ago, the two finally met at a film festival, and Ellison came away from that meeting with renewed motivation. “If you have something inside of you and you are coming from a good place, you can do great things.”

For information about film screenings, contact Brian Ellison at unmaskulinity@gmail.com or 281-914-1941. To donate, visit the GoFundMe page at gofundme.com/fsqeq-the-unmaskulinity-project.

This article appears in the September 2019 edition of OutSmart magazine.