Seduction in the Surfaces

Contemporary Arts Museum Houston spotlights gay artist Nicolas Moufarrege through Feb. 17

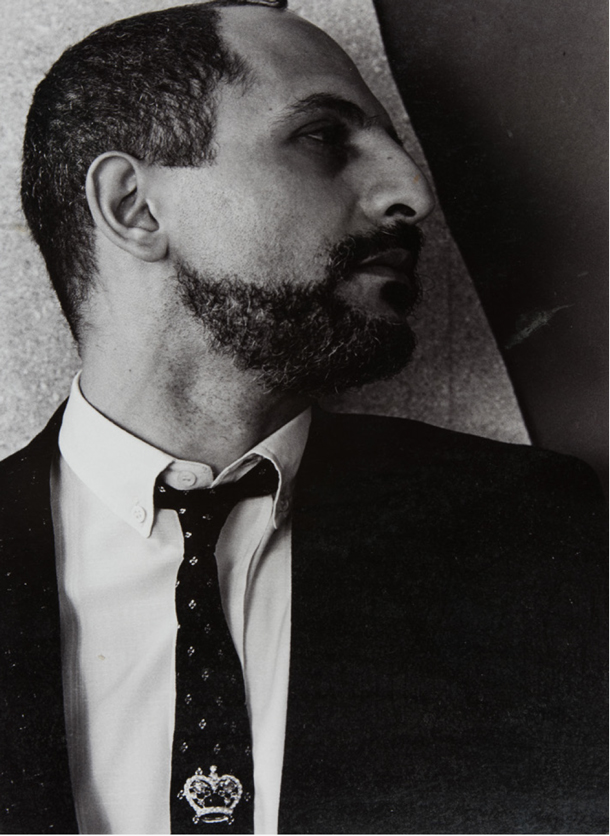

Queer 1970s artist Nicolas Moufarrege exuberantly embraced a wide array of disparate elements in his work: embroidery; Islamic wall tiles; appropriations from Picasso and pop-artist Roy Lichtenstein; buff, homoerotic male nudes; and comic-book heroes like Spiderman. Even Santa Claus makes a surprise appearance in his tableaux late in Moufarrege’s career.

A true citizen of the world, Moufarrege’s journey took him from Beirut to Paris in the mid-1970s, and to New York City in the early 1980s—a time when the burgeoning downtown art scene burst forth with extraordinary vibrancy. He integrated influences from East and West into his artistic practice. He was also a curator and critic. In these roles, he helped bring to light the works of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Fab 5 Freddy, Greer Lankton, and David Wojnarowicz when the East Village arts scene was blossoming.

A decade of exhilarating creativity was cut tragically short in 1985 when Moufarrege was felled by complications from AIDS at 37. In the view of Roberta Smith, co-chief art critic of the New York Times, he left a unique legacy.

“It’s hard to characterize the combination of decorative intensity, measured calm, and generous pictorial wit that Mr. Moufarrege (and the craftspeople who worked with him) wove into his surfaces, but it seems to define some unique midpoint between American and Eastern Mediterranean cultures,” Smith wrote in a review of a posthumous 1987 exhibition of his works.

“Mr. Moufarrege’s work bridges traditional factions of East Village art. It combines conceptually-based appropriation with the visual energy of the graffiti art made famous by the now-defunct Fun Gallery, where the artist’s second one-man show opened a few days after his death.

“But Nicolas A. Moufarrege lived long enough to become completely himself and to make art that reflects a particular time and place, while also transcending them.”

Three decades after his death, the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston presents the artist’s first solo museum exhibition, Nicolas Moufarrege: Recognize My Sign, which has been organized by CAMH curator Dean Daderko and is on view through February 17. The exhibition will then travel to Queens Museum in New York from October 5 through February 16, 2020.

For Daderko, Moufarrege’s oeuvre remains remarkably fresh. “I think that a lot of people are surprised that this work was made in the 1970s and 1980s,” he observes. “It looks like a lot of work that artists are thinking about and making currently.

“He was living in the East Village in New York City in the 1980s. It was still a gritty place, and home to many artists living cheek-by-jowl in cold-water flats,” continues Daderko. “They put together exhibitions in small artist-run spaces. His work from the 1980s—with all its glitter and brooches and fake gems pinned to the surface—has a bit of this gritty glamour, which I think is really attractive. These appeal just as much to folks today as it would have then. There’s a type of seduction in the surfaces.”

Finding his métier quite by accident.

Born in Alexandria, Egypt, to Lebanese Christian parents in 1947, he studied chemistry at the American University of Beirut. In 1968, he came to America to continue his chemistry studies at Harvard University on a Fulbright grant, earning a master’s degree. While there, he developed a hole in his jeans and couldn’t find a patch to his liking to purchase. He embroidered a strawberry patch, and thus discovered his passion for embroidery. (The first room of the exhibition contains some wonderfully casual snapshots of a young Moufarrege ebulliently modeling some of his patches on his blue jeans.)

He returned to Lebanon, and in 1973 held his first exhibition at Triad Condas gallery in Beirut, featuring a number of modestly sized portrait tapestries. He called his works “experimental weavings,” and the Lebanese artist Etel Adnan observed, “This is how traditional craftsmanship becomes a personal art full of promise.”

In 1975, with a civil war about to erupt in Lebanon, he relocated to Paris. Although he was an immigrant adapting to a new culture, his work continued to evolve. “In Paris, the scale of the work increases a great deal,” Daderko notes. “That is certainly a reference to European-painting traditions and easel-painting traditions. But what he is doing is stretching an embroidery canvas.

“It feels like Nicolas is thinking about the place that he left, and the people he left behind. He’s pulling from different cultural traditions. That sense of intellect is in the work—this real curiosity about other cultures.”

In 1981, he moved to New York City and came into his own, both professionally and personally. In an essay in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition, critic Kaelen Wilson-Goldie notes of this period, “Moufarrege was a fabulous gay man from a deeply conservative family and culture. In New York, none of that seemed to weigh on him. His work celebrated the many worlds that had made him, without finding fault in any of them.”

“The moment he gets to New York, there was a movement called ‘Appropriation,’” Daderko observes. “This involved artists taking things from other artists, borrowing them, and often making direct copies of things. They were questioning ideas about originality, about authorship. Nicolas establishes himself as someone participating in dialogues around appropriations.”

In Manhattan, his work was influenced by other gay artists including Andy Warhol and Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden, a German photographer in the late nineteenth century known for his homoerotic photos of nude Sicilian men.

In 1985, Moufarrege developed a rash on his skin, and within weeks was diagnosed with HIV. In the early days of the AIDS crisis, when fear and loathing reigned, he struggled to find a hospital in New York City that would accept patients with AIDS.

When he passed away in 1985, he was one of the first artists we knew personally who was lost to the AIDS epidemic,” recalls Daderko. “He was surrounded at the end by a loving group of family and friends alike.”

Moufarrege’s family, based in Shreveport, Louisiana, has been instrumental in preserving the artist’s work. “Nicolas was so deeply loved by his family, and so deeply supported,” commented Daderko.

Daderko has been looking forward to staging a solo exhibition of Moufarrege’s work for over a decade. He feels that the moment is ripe for a rediscovery of the artist, both in Houston and later this year in New York. “As someone who passed away in 1985, there are a lot of people who knew him as an artist and a writer,” Daderko says. “Because of his absence for several decades, I think that people are ready to rediscover his work. I also think that an entirely new generation of folks will be able to discover his work.”

What: Nicholas Moufarrrege: Recognize My Sign

When: Through February 17

Where: CAMH, 5216 Montrose Blvd.

Info: camh.org

This article appears in the February 2019 edition of OutSmart magazine.