The Notorious R.G.G.

Queer Latino poet Roy G. Guzmán on his new anthology, ‘Pulse/Pulso: In Remembrance of Orlando.’

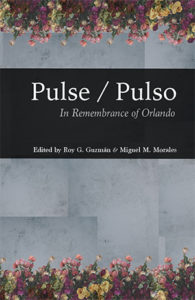

Co-edited by queer writers Roy G. Guzmán and Miguel M. Morales, the breathtaking poetry anthology Pulse/Pulso: In Remembrance of Orlando (2018, Damaged Goods Press) is a literary tribute to the 49 lives lost (and 53 wounded) at Orlando’s Pulse nightclub in June 2016. Featuring the work of 18 poets, including Caridad Moro-Gronlier, Chen Chen, Baruch Porras-Hernandez, Monica Palacios, James A.H. White, and Tessara Dudley, Pulse/Pulso is a powerful, poetic memorial to lives lost and forever changed on that fateful night. Guzmán, who is currently pursuing a doctoral degree at the University of Minnesota, spoke with OutSmart about the anthology, challenges the editors encountered in the publishing process, his own writing, and more.

Gregg Shapiro: Do you remember where you were when you first heard about the shooting at the Pulse nightclub?

Roy G. Guzman: Yes, I definitely do. I was having a hard time sleeping and woke up in the middle of the night to use the restroom. I checked my phone, and at first I couldn’t believe what I was reading on Twitter. The shooter was still inside and authorities couldn’t say how many people had been killed. Pictures of cops and people who’d been at the club were being shared. I’ll never forget those images. I remember going back to bed and, in the dark, trying to catch a glimpse of my boyfriend at the time. I started to cry. Many of us will never forget that night.

You grew up in South Florida. Had you ever been to the nightclub prior to the shooting?

I have been to lots of clubs in Orlando, but never to Pulse.

Did you write any poems in response to the tragedy?

Did you write any poems in response to the tragedy?

My poem, “Restored Mural for Orlando,” was borne out of those chaotic days. There was so much I was trying to contend with. I was afraid. Like many others, I too was grieving. At first, I felt this ineffable sense of misery. I had already finished my second year in the MFA program. I’d speak to my friends in Miami and we’d exchange our disbelief. About a day after “Restored Mural for Orlando” appeared on NPR’s Latino USA, my friend D. Allen contacted me about the possibility of turning the poem into a chapbook that would also have a Spanish translation, which Marco Antonio Huerta completed. For the next year or so, we were able to raise over $2,000 for the victims and for Pridelines, an organization in Miami that was incredibly supportive of me when I was struggling with my queerness. The chapbook has also been taught in several colleges around the country.

What can you tell me about the process of soliciting work from poets for the anthology?

The anthology was originally supposed to come out through a publisher that has since gone defunct. After reading “Restored Mural for Orlando,” they solicited me to become an editor, but I told them I couldn’t take on such a project without a co-editor. I am so grateful that, after a few heart-to-heart exchanges, Miguel came on board. From the beginning we decided we had to publish work exclusively by queer and trans people of color, since we were seeing more straight white writers take lots of space. We made an extensive list of authors we wanted to solicit, with the intention of accepting poetry and short nonfiction pieces. We also made sure the call for submissions wasn’t just soliciting work from our acquaintances, and that connected us to many people we didn’t know. We read submissions in Spanish, although none of those made it to the final round.

You describe how the process of finding a publisher for the anthology was marked by “elitism, classism, and a blatant disregard for queer and trans people of color and indigenous peoples.” Did this come as a surprise to you?

I can sometimes be a gullible Gemini. Or too idealistic. It’s not that I didn’t imagine we’d face these challenges; it’s more that we were struck by the severity of so many microaggressions. Editors questioning the validity of the anthology, questioning why we’d chosen certain pieces, wanting to reroute the entire project, questioning Miguel’s Puerto Rican background, because most of the victims were Puerto Rican. Editors telling us the anthology wasn’t long enough, that it wasn’t academic enough, that it needed more content from established voices, that everything that had to be said about Pulse had already been said and that that chapter was over. Editors telling us that a writer responding to a tragedy doesn’t automatically make it publishable, as if Miguel and I had never edited anything before.

It was cruel and disheartening. Above all, we believed in the work and had to apologize to our contributors for the time it took us to find a home for the anthology. Miguel and I learned so much about community through this process.

Poets have a long history of being vital voices in times of crisis; there are numerous anthologies addressing the AIDS crisis, race, and war. Can you say something about the healing that can occur from reading, as well as writing, poetry?

Someone said that poets are the new journalists. While I can agree with the spirit of that statement, I’ve been lucky to see all the places I hadn’t thought poetry could walk into.

I know reading and writing poetry became highly restorative for me. It can still move me in ways that other things rarely do. I also think poetry anthologies, in particular, serve an important place in literature by showing us and exemplifying new forms of community, visibility, accountability, responsibility, history, and the future. I’ve seen people cry after reading a poem. I’ve seen how poetry can change a person’s life. It’s like a second birth.

When did you start writing poetry?

I started dabbling in poetry back in high school. During my freshman and sophomore years, I attended William H. Turner Tech in Miami, and there I met some fellow rockers. We’d write fan poetry inspired by the Smashing Pumpkins—you know, the kind of poetry one writes before inevitably reading Niet-zsche. [Laughs] The title of one of my poems was something like “We Are the Machines of God.” [Laughs] I’d carry a wallet with a metal chain strapped to my belt loops. That’s when I first read Amy Tan and James McBride, and connected so much with their work. That’s also when I started writing poems inspired by Emily Dickinson. I guess you can say Emily became my first patron saint in English. Rubén Darío was the first poet whose work found my heart.

Are you strictly a poet, or do you also write prose?

I am probably 85 percent poet. I like how coming up with that random percentage is suddenly making me feel like an impostor! [Laughs] I write a lot of academic essays and have published book reviews—and long Facebook posts. [Laughs]. I took a fiction workshop and a few nonfiction classes for my MFA degree. I am in awe of prose writers’ relationship to productivity. I love writing short stories, and I’ve written a few, but afterward

I feel like going on a long vacation. [Laughs]

I also have a complicated relationship to genre, because I’ve seen how it stifles one’s creativity and understanding what the subject matter actually wants for itself. I’m always suspicious of genre.

What can you tell me about your forthcoming debut poetry collection?

At the moment, the collection is titled Catrachos, and Graywolf Press will be publishing it in the spring of 2020. Immigration, violence, queerness, poverty, racism, language, despair, and hope are some of the themes I look at. Florida is the setting for many of these poems, as is Honduras, my birthplace. I want these poems to grieve with you, to dance with you, to confide in you, and to listen to you. I feel incredibly grateful to get to write and share this work.

This article appears in the November 2018 edition of OutSmart magazine.