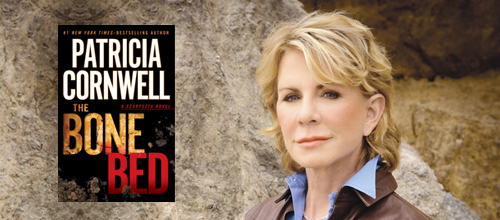

How lesbian author Patricia Cornwell became ‘the mother of CSI’

by Kit van Cleave

Photo by Matthew Sukkar

(Includes web-only additional interview material.)

Patricia Cornwell, the fantastically successful author of the crime novels about Kay Scarpetta, Medical Examiner, has brought out her twentieth book, The Bone Bed. It’s about a series of strange happenings, starting with an unnecessary testimony in court which Scarpetta really doesn’t need to make—it’s politically motivated. Then a body shows up in Boston Harbor entangled with a giant leatherback turtle.

Cornwell’s career as a writer has often been covered by the national media for many reasons; one is that she’s an out lesbian married in 2005 to Staci Ann Gruber, an instructor of psychiatry at Harvard. Her novels have sold more than one hundred million copies. Cornwell took time from an extremely busy schedule to give an interview to Kit van Cleave.

Kit van Cleave: Your Postmortem, which came out in 1990, was written in first-person.

Patricia Cornwell: The first ten years, my books were written in first-person. Then after 2003 I decided I wanted to expand my range as a writer, and thought the fans might like it better if I did third-person because then they could “watch it more like a movie.” I found out, to my dismay, that the fans did not like that as much.

They wanted Kay Scarpetta’s point of view.

They do. A couple of them on Facebook and Twitter made comments that the reason they love having her point of view is they feel they are working the case with her. It makes them feel smart.

I hadn’t thought about that before.

First-person does limit scope. All the reader gets is the narrator’s perspective. But some people think it’s easier.

In Port Mortuary in 2010 you went back to first-person and then continued that with The Bone Bed.

Do some people think Scarpetta is demanding and difficult?I was in law enforcement, so I believe in some fields one must be absolutely evidentiary and correct.

You’re right about that!

You emphasized that point when Scarpetta is dragged into court to testify. I don’t see her as demanding. Evidence is either right or it’s not.

It’s always a pleasure to talk to somebody with your experience. You know exactly what this is all about. On a crime scene, there’s only one way to collect evidence, and that’s the right way. If that makes Scarpetta difficult or demanding, better that than to have the whole case get thrown out of court. It’s not [about] the personality of the medical examiner or the police officer. It’s a field which requires that kind of scrupulous detail.

The Bone Bed is your twentieth Kay Scarpetta book. Part of your success is the meticulous research you do in developing plotlines with your medical examiner, Scarpetta. In this novel, you link dinosaurs to the existence of a very old, rare turtle. Could you discuss this?

The Bone Bed is your twentieth Kay Scarpetta book. Part of your success is the meticulous research you do in developing plotlines with your medical examiner, Scarpetta. In this novel, you link dinosaurs to the existence of a very old, rare turtle. Could you discuss this?

That was really fun. Two aspects of my research for The Bone Bed caused it to become a special book. I didn’t really anticipate this when planning it. The first is that even before I finished my last novel I was doing work with the New England Aquarium and their animal rescue people. Scarpetta’s office is not that far from the Boston Harbor, so she can certainly get some water scenes. I became aware of what goes on in that area. These wonderful creatures get entangled in fishing lines, which is heartbreaking. We live close to the harbor, so I know a whale can get stranded or entangled with a vertical fishing line and drown. People forget that these mammals and reptiles have to be able to breathe. They can’t stay in the water forever. It’s a continual hazard for the fishing industry. So I got interested in learning more about marine biology. For two years I worked with these rescue people, who taught me all about sea turtles [in the rehab water tanks they have] for these creatures. The leatherback turtle is most interesting; it cannot be seen in captivity. It’s one of the most prehistoric creatures left on earth.

So the link to the dinosaurs is not fiction?

No, it really isn’t. The other strange aspect came a year ago this past summer, when Donna and Danny Ackroyd called and said, “We’re taking some people to Alberta, Canada, on a dinosaur dig. Would you like to go?” I thought it was pretty hard to turn down. So I found myself digging for these seventy-million-year-old bones, and they turned out to be from the same era as the leatherback turtle. We still have a few of those turtles alive today, but they’re rapidly becoming extinct.

So I had this thought about a world-class paleontologist in Canada doing the same dig that we were doing out in the muck and the rain on a deserted campsite in the wilderness, and she vanishes into thin air from the dig. Thousands of miles away, Scarpetta’s getting a strange anonymous e-mail while she’s cooking dinner, which leads to her rushing out in a Coast Guard boat where a body is tethered underwater and has gotten entangled with this giant leatherback turtle. So there’s a double-whammy of this turtle having to be disengaged so it doesn’t drown, and her having to preserve an underwater crime scene and figure out what on earth is going on.

The turtle becomes a little bit of a tattletale, because this 2,000-pound creature has a bit of barnacle in its left flipper carapace. That barnacle has a trace of something on it. She has to extract this from this massive creature and find out what it might tell her about the dead person. She has to reconstruct the events.

I was also lucky that during my research the aquarium staff did get a stranded leatherback, and I was able to actually see one. They brought it into the marine rehab. Unfortunately, that poor creature didn’t make it. It made me so sad—it was tangled up in fishing line and in bad shape. But I at least got to see one of these incredible creatures up close, smell it, feel it. So when Scarpetta’s working on it on the back of the fireboat, I can accurately describe it, make it real.

So the talk about your being “the mother of CSI”—do you find that amusing?

I don’t even watch these procedurals on TV. I don’t regret anyone being entertained by these shows, but a lot of difficulties are caused out in the field because of them. I have arrived at a crime scene, a burglary, and when the victims open the door [I discover] they’ve already bagged and labeled all the evidence. I saw two of these in one day. When the second person did it, I asked, “Why did you touch everything?” And the lady said, “Well, I watch all these shows, and evidence is not as important as it used to be.” Police are up against huge odds trying to get the public to understand that what they see on TV is not necessarily the way a case would be worked in real life. Juries are having tough times with this, too.

You had three books rejected before 1990. They were not Scarpetta books, right?

They were crime novels in which Scarpetta was a minor character. In each book she became more dominant. Those books weren’t really very good. I would never allow them to be published. They were my learning models, finding out what I was doing. Then the fourth attempt was Post Mortem, which made the rounds for a good eight months before it was finally accepted. It was rejected by almost every major publisher in New York. So I was already looking for a job. I was at a morgue where I’d gone to learn all about medical examiner work. And by 1988 when that book was floating around and getting rejected, I started going back to newspapers to see if anyone would hire me as a journalist again. I said to myself, “Not only are you three strikes and out, you’re four strikes and out to find yourself.”

I don’t think you have to worry about that any more. [Cornwell is often billed as the second most financially successful female writer of her time after J.K. Rowling.]

You have two female characters, both wearing heavy rings on their index fingers. One is a silver coin ring and the other is a heavy gold ring. What is the significance of that to you?

The coin ring is on the victim in the underwater crime scene, and the gold ring is worn by Scarpetta’s niece. It raises the question in the first case as to whether that was her ring or belonged to someone else or fit a different finger. That victim is so mummified, having lost forty to fifty percent of body weight, that a ring which might have fit on her ring finger now would barely even stay on her index finger. With Scarpetta’s niece, Scarpetta realizes it may signify something her niece is not telling her. Sometimes these little details woven throughout a plot make the reader ask questions about all of it.

You’re so specific about medical details, but in the midst of your busy career you never went to medical school. Was that something you just couldn’t ft in? Or didn’t it interest you?

I was an English major. I’m first and foremost a writer, and the rest of the time I’m a student trying to learn what the real police and real medical examiners do. I look at my life as, “I fight crime with a pen.”

What’s the status of your Jack the Ripper project?

I’m finishing the revision after ten years, and we’re due to bring it out next summer. It will have new evidence in the rewrite, and I’m going to put all my scientific reports on my website and invite the world to come and investigate it for themselves. It will be fun.

You married in Massachusetts. Your dad, Sam Daniels, was an appellate lawyer. Do you wish to make any comment about the New York appeals court declaring the antigay DOMA law unconstitutional?

It certainly should be called unconstitutional. It’s about equality and human rights. I didn’t get a chance to actually read that result completely because I’m traveling, but if I understand it correctly, that seems like a really positive move.

Of course you had no trouble getting married in Massachusetts anyway.

No.

One more question. I noticed your family was Republican and you were friends with Billy and Ruth Graham. Do you have any thoughts about the overall election?

Those two aspects are interconnected because for me it’s not about groups but about individuals. I’ve voted both sides of the net and contributed to both parties. I’m not really close to the Graham family, but I was to Ruth, who was a remarkable person. I’d say the same about this election—it’s not about either party, but about who is going to best represent the American citizens, and who is going to be the most truthful about issues. Politics is becoming very fear-driven instead of freedom-driven. People have a right to vote any way they want, but most of all they have a right to the truth. If a politician stands up for an issue, he shouldn’t change his mind five minutes later playing “fetch” because he wants the next few points he can score. Be honest; tell the voters what you really stand for, and stand on it. Even the bad news—let us know what to expect and what we can do about it.

I very much appreciate the time you gave me today. Thank you.

My pleasure.

Kit van Cleave wrote about opera and theater director Francesca Zambello in the November issue of OutSmart magazine.