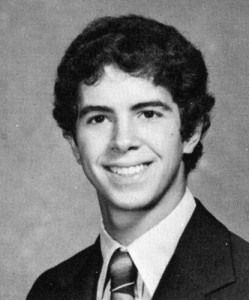

Activist Peter Staley and director David France discuss their new film

by Rich Arenschieldt

Everyone at Conestoga High School in Berwyn, Pennsylvania, knew both of us back in the ’70s. I was the outspoken dorky musician, and Peter Staley was the prankster who threw legendary parties at his home in suburban Philadelphia. We both began our careers in banking as bond traders and, unbeknownst to each other, ended up working in the HIV/AIDS “movement” during the dark pre-protease days; Peter entwined with New York City activists and me interacting with HIV patients and their families in Houston.

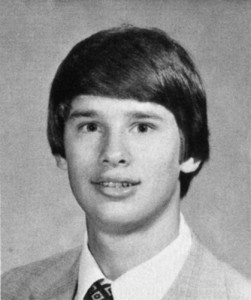

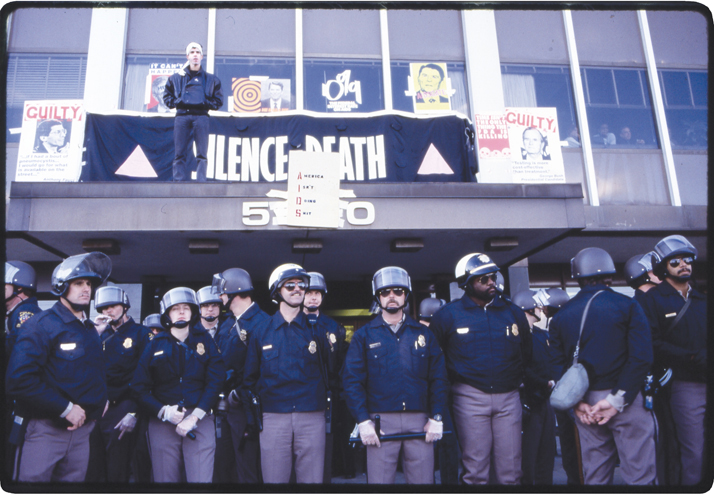

So when I saw Peter hanging a banner atop the Food and Drug Administration’s entrance in David France’s new documentary How to Survive a Plague, it wasn’t shocking as much as it was a somewhat belatedly expected surprise. The film has now entered into the cinematic canon that chronicles and honors the work of AIDS activists and others nearly 30 years ago.

In New York City, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP)—“a diverse, non-partisan group of individuals united in anger and committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis”—formed.

“I was diagnosed in 1985,” Staley says. “I was working as a bond trader in New York and was deeply closeted—a necessity, given the macho corporate culture prevalent in the financial industry. On my way to work one day, I literally stumbled into an ACT UP demonstration in progress. I attended the very next meeting; there were at least 100 people in the room. And, after ACT UP’s astounding presence in the 1987 New York pride parade, with their now-famous ‘barbed wire concentration camp for Reagan’s AIDS victims’ performance float, the number of gays and lesbians at subsequent meetings increased exponentially.

“Those involved were very diverse,” Staley continues. “There were some old-timers from the Stonewall era as well as lots of young people—many of whom had recently lost a lover or were themselves newly HIV-infected. Interestingly, gay men and lesbians coalesced on this issue—something that people weren’t accustomed to. Men and women had previously inhabited their own specific social venues.

“Everyone was desperate to find a communal outlet for all the emotions that they were experiencing at the time, the most predominate of which were rage and anger at being ignored by those who wielded political power. The energy at the meetings was palpable—almost like a religious revival.”

In the mid-1980s, most of the gay community was closeted; those who were “out” were essentially segregated or marginalized from society. “All of a sudden, there was instantaneous local and national press covering gay and HIV-positive people marching in the streets during ACT UP demonstrations,” Staley says. “This was jarring to the national conscience.

“It’s important to remember that this was six years into the crisis. The collective anger had percolated to such a point that the GLBT community realized that something radical had to occur to move the concerns of PWAs to the forefront of the national dialogue. We had to get in the faces of politicians, drug companies—anybody who could help us survive. That acute fear and sadness that so many of us experienced finally burst, precipitating action. As a result, people flooded to us. We simply had to discover the courage to break out of our respective closets. This process was fueled only by word of mouth—groundbreaking in that it materialized decades before the advent of anything resembling social media. What [director] David France did with this documentary is absolutely amazing,” Staley says. “I still can’t believe it’s his first film.”

Providing insight into his motivation, director France explains, “For years, the work of ACT UP and others had never been seriously acknowledged in any enduring way. The people involved in this movement had always been minimized; regarded merely as radicals, part of a disorganized protest movement—never honored for what they had accomplished in a historical context. I sought to change that.”

A fortunate coincidence of technology also played a part in the film’s creation. “HIV came into existence at about the same time as the hand-held camcorder, which was invented in 1982,” France says. “That enabled almost anybody to film primary source material from the epidemic as it was occurring, in real time. Additionally, many people were working on various projects, all of which involved documenting the events surrounding the movement. Journalists, documentarians, and performance artists were all chronicling events. Several were recording at protest sites just to ensure that the police didn’t mistreat protesters.”

Many in New York’s creative community were HIV-positive, and their contributions are especially striking. Artist (and Texan) Ray Navarro is featured in several haunting vignettes as he provides a detailed and personalized videography of his experience.

The film’s strength draws from its skillful amalgamation of various events, all with a common thread, carefully assembled in a manner that allows audiences to watch difficult subject matter without becoming emotionally exhausted—a skillfully paced retrospective that still feels relevant to worldwide current events.

France credits many “sleuths” who helped him unearth important source material. “Initially, it was a bit like detective work that took years to complete. We established identities of individuals in various ACT UP videos, located them, and then found their friends and families, hoping that they might have additional footage we could use. It was a very ‘hands-on’ endeavor,” France says.

“When we wanted to find film of a particular arrest or action, we would draw a map of that particular demonstration, as we remembered it. From that, we would try to discern where certain individuals were when they were arrested and who else may have had a camera at that same location. We spent a lot of time just trying to figure out who we had on the ground at certain times and places.

“I viewed hundreds of hours of video that came from 33 people,” France says. “Amazingly, all but one are still living and able to recollect the events that occurred. Each time I found something, it would lead me to another person, in a different location, shooting additional video. I wanted to bring the viewer into each demonstration, to give them a sense of what was happening at that moment.”

“Over the years, there had been lots of talk from ex-ACT UPers about documenting what had occurred,” activist Staley remembers. “For one reason or another, it never came to fruition. Throughout history, if you look at communities that have endured a shared traumatic experience, it usually takes about fifteen years for those most affected by the events to begin looking back. This is true with the Holocaust—most of that great commemorative literature came out after about fifteen years, and similarly so with Vietnam. In HIV, we are now fifteen years away from the major breakthrough in treatment [the advent of protease inhibitors] that slowed the death rate by 80 percent.”

Many of the players in the film opened their personal “archives” to France, essentially giving him carte blanche to create what he wished to. “David approached me first with the idea for the film,” Staley says. “We were familiar with each other—over the years he had written with a beautiful eloquence about AIDS. I knew he had a profound understanding of everything that had taken place during those years, and I trusted his creative vision for the film. He came to my apartment and cleaned out my video library.

“David was the perfect person to accomplish this,” Staley continues. “As a journalist who wasn’t [active in ACT UP], his objectivity enabled the film to present our history fairly, including all of the rifts that occurred within ACT UP through those turbulent years.” France was, in fact, on the periphery of the activist movement because his partner, Doug Gould (to whom the film is dedicated), was HIV-positive at the time.

France was cognizant of ACT UP’s changeable nature and was well-acquainted with its idiosyncrasies. “It was a true democracy,” he says. “All the important players had detractors, as well as groups of people who worshipped them. Key individuals brought specific skill sets to the group. Mark Harrington and others studied the science, Peter Staley was the guy on the ground who ultimately built bridges to the pharmaceutical companies, and ACT UP founder Larry Kramer was the organization’s eloquent voice.”

The film is built around a pivotal scene when Kramer quells dissention at a particularly riotous gathering. “Footage we discovered showed him in the midst of a meeting, being pummeled by people who disagreed with his views,” France says. “Kramer’s stentorian announcement of ‘Plague!’ quelled all the warring factions present and served to galvanize the community. When he shouted, people listened.”

Staley has a similar reverence for ACT UP’s founder. “Larry Kramer is a father figure to me,” he says, “and someone whose approval I will be forever seeking. Though I wasn’t in the room during that crucial moment, his words encapsulated the essence of the entire movement better than any I have ever heard. It was perfectly timed and brilliant.”

As ACT UP morphed into a larger version of itself, things became powered by their own momentum “Within ACT UP there were various committees and affinity groups, doing a variety of different things,” Staley says. Certain activists were quickly rising to prominence through their work on the Treatment and Data Committee. “This was the group that focused on getting treatment to people, convincing pharma, the FDA, and the NIH to accelerate drug development and access,” he says. “To accomplish this, we had to train ourselves to become experts in the research process, drug approvals, and the inner workings of various federal agencies. We started pushing all the relevant players to do their work faster.”

Key members of that committee had begun to dialogue with government and industry directly, something that sparked resentment among the larger ACT UP membership.

In retrospect, Staley realizes that some mistakes were made. “We became a bit elitist,” he says, “and didn’t always communicate effectively with the membership. The core members of the Treatment and Data Committee believed that their work was crucial to the organization’s mission. We felt that other participants in ACT UP were trying to ‘reel us in’—essentially to put the committee ‘in its proper place.’

“There is no doubt that we were divas,” Staley says. Participants in various meetings who offered less-than-stellar ideas would receive withering looks from committee members who perceived themselves as the smartest people in the room. “As with many similar organizations,” Staley recounts, “prima donnas abounded.

“We felt that our work was being seriously threatened by internal organizational dissent that could not be amicably resolved. For our own sanity we needed to spin off from ACT UP, and in 1991, the Treatment Action Group (TAG) was created.”

That split marked a watershed moment in AIDS activism. According to director France, “TAG viewed themselves as being on the leading edge of the struggle. They became the ‘intelligentsia’ of the movement, and consequently sparked resentment from other activists—something the TAG guys didn’t have the time or patience to deal with.”

In addition to the structural and organizational tumult that transpired, many intimate and intensely personal emotions permeate the film. “The funeral march of activist Mark Fisher inspired a profound eulogy from activist Bob Rafsky,” France says. “Bob’s words comprise one of the memorable orations of the movement.”

One of the strengths of this film is that it instantly transports viewers back to a specific time and place and inserts them into the action—be it a hospice, a federal building, or a demonstration. Staley remembers that “regardless of where you were, there was chemistry among everyone who experienced that same fear, emotion, and companionship.”

When questioned about his personal feelings after viewing the film, Staley says, “Many of us who have been involved with the film were shocked at how quickly those suppressed memories came to the surface. The resurgence of emotion was surprising—all [emotions], not just the painful ones. I remember the joy of the time. The camaraderie, the family, the sheer headiness of the work and the victories we were celebrating, the dark humor—it all came back.

“We had all done such a splendid job of putting those events on a ‘high shelf’ and making them emotionally inaccessible. That was just a coping mechanism to simply survive the day-to-day challenges we encountered. We had buried so much, not just in terms of friends, but also with regard to the emotions of the era.”

The film has allowed Staley and others to finally confront the worst aspects of the epidemic. “There’s a lot of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder from those ‘plague’ years,” he says. “When we realized that we were going to live into the future, many activists couldn’t cope and ended up with lots of issues.

“Watching the world continue around us as if nothing had happened was tough. Even the gay community was collectively fatigued; they just wanted it to be over with. It was just so painful, we couldn’t even journey back to honor what we had done and those that we had lost—something the film now does. It also helps us to remember that amazing things are possible, and serves as an inspiration to propel similar future endeavors.”

Director David France offers a historical perspective: “Even the movement’s most severe detractors now realize that AIDS activism had a lasting and permanent impact on healthcare in America. It changed the drug approval process, improved access to treatments, involved communities in issues specifically affecting them, and gave affected individuals a seat at the table to determine how they would be affected by decisions made for treatment of all diseases.

On a more personal historical note, Peter Staley reminds me of our time in high school: “I was setting off fireworks from the roof of my house during those now-infamous parties. I’ll probably continue to climb on buildings and create havoc whenever and wherever I am needed to do so.”

Rich Arenschieldt is a frequent contributor to OutSmart magazine.