Black lesbians and their families strive for visibility—and find it in a new book

by Kit Van Cleave

(EXPANDED VERSION FOR THE WEB)

The distinguished scholar and researcher Dr.Mignon R. Moore speaks at Rice University on February 1, in a presentation hosted by Race Scholars at Rice and the Center for the Study of Women, Gender and Sexuality.

Dr. Moore is Associate Professor of Sociology and African-American Studies at UCLA. Prior to joining UC, she completed her graduate work at University of Chicago and held a Ford Foundation post-doctoral fellowship at University of Michigan. She has published frequently in the fields of sexuality, race, family, gender, aging, and adolescence.

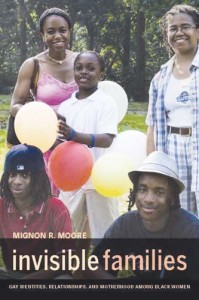

Her new book, Invisible Families: Gay Identities, Relationships, and Motherhood among Black Women, was published in 2011 by University of California Press. She kindly agreed to give OutSmart a brief preview of her Rice presentation.

Kit Van Cleave: What kind of social categorizations does your research emphasize?

Mignon Moore: In my research, I pay close attention to what I call “intraracial variation” in the lives and experiences of black lesbians. Social class figures importantly in the lives of the women in this book. About one-third of the women grew up very poor, meaning they lived in impoverished rural areas in the Caribbean or housing projects in New York. Their parents worked intermittently and were sometimes addicted to alcohol or drugs. They spent some portion of their childhoods being raised by a grandparent or in foster or group homes.

Another third of the women in my book grew up working-class, meaning their parents held a job but they still struggled to make ends meet. They were sometimes raised by a single mother, and began working at an early age to help contribute economically to the family. They held jobs like administrative assistant, security guard, retail sales clerk, or telephone linesman. They also assumed early responsibility for their siblings while their parents worked.

The remaining third of my sample grew up in middle-class households, holding jobs like teacher, director of nonprofit organization, sales manager, or accountant. One or both of their parents held a college degree, their parents were stably employed in middle-class jobs, they had more than enough to eat, attended good schools, and participated in extra-curricular enrichment activities. And 13 percent were upper middle-class, in occupations like attorney, physician, and college professor.

The remaining third of my sample grew up in middle-class households, holding jobs like teacher, director of nonprofit organization, sales manager, or accountant. One or both of their parents held a college degree, their parents were stably employed in middle-class jobs, they had more than enough to eat, attended good schools, and participated in extra-curricular enrichment activities. And 13 percent were upper middle-class, in occupations like attorney, physician, and college professor.

In the book, I show how social class affects their experiences as openly gay women. Professional women experience less discrimination from their families and members of the community. These women were often “firsts,” meaning the first black person to integrate their high school, the only black person in their law firm, or one of the only black women in their medical school class. These experiences of upward mobility are shaped by race, and race figures importantly in their self-understanding.

How do the women you interviewed regard various labels, such as “gender-bender,” “transgressives,” or “straight-up lesbians”?

In Chapter One, “Coming into the Life,” I show how black lesbians “come into” an understanding of themselves as gay (rather than “come out”) through predominantly black and Latina lesbian social spaces. This influences how they come to think of race, gender, and sexuality within their own bodies.

I identify four pathways by which black women come into the lesbian life:

• “Straight-up” gay women understood themselves as “different” from others at an early age (most were self-named “tomboys”). They either self-identified as gay at an early age, or they de-emphasized any sexuality until adulthood. They are the most likely of all categories to dress in gender non-conforming ways.

• “Conformists” also experienced same-sex desire at an early age, but had a major sexual relationship with a man before coming to terms with their gay sexuality. Many of the women who were born in the Caribbean or other places outside of the U.S. fit in this group.

• “Hetero-identified” lesbians do not feel different from heterosexual women. They did not report any same-sex attractions in childhood or adolescence, and first initiated a gay sexuality after being attracted to or having a romantic encounter with an openly gay woman.

• “Sexually Fluid” women avoid labels like lesbian. While they might currently be in a relationship with a woman, they say it is possible in the future that they will date a man.

In Chapter Two, I identify three presentations of gender: femmes, gender-blenders, and transgressives. Femmes (48 percent of the sample) are feminine-identified women—they wear high heels, makeup, and feminine jewelry. They mostly partner with gender-blenders or transgressive women.

Gender-blenders (34 percent of the sample) combine both aspects of femininity and masculinity to create a unique look. They may wear men’s pants or shoes and combine them with a form-fitting top or makeup.

Transgressive women (18 percent of the sample) use the female body as a sight for masculinity. They look the most “boyish” and in other groups are similar to butch or stud women.

Middle-class women had the most difficult time identifying categories for themselves, mainly because they were not comfortable openly saying they dress in a less-feminine manner. However, regardless of class, all of the women could place themselves in one of these three categories. Middle- and upper middle-class women were the least likely to report a transgressive gender presentation. I also talk about the dangers of black masculinity in the way society perceives black men, and how that affects the safety of transgressive lesbians.

Much of the first part of your book has to do with identity, as in whether your subjects see themselves primarily as lesbians, as blacks, or as women. As you know, the work of French psychologist Jacques Lacan influenced contemporary ideas about The Look and The Other. Do you think a child’s sense of identity comes from seeing oneself in the mother’s eyes, in a mirror, or through another event?

When it comes to group membership, black lesbians feel most strongly connected to the larger community based on race.

For example, when I ask “Which identity is most important to you: your identity as a black person, as a lesbian, or as a woman?” the response might be “as a woman.” But when I ask about collective identity, or the group they perceive themselves to share the most common ground with, they usually choose blacks as the group, rather than women or lesbians. These are women who were mostly born in the 1960s and ’70s, during a time when race was particularly salient to their sense of community.

What do you think happens when one is in a interracial relationship? How would this affect both partners’ self-esteem?

Five families in my book are interracial (black/white) couples, and no one mentioned specific obstacles. Being in an interracial relationship did not appear to limit the black member of the couple’s participation in various aspects of black community life. It did, however, increase their likelihood of participating in predominantly white lesbian communities.

I didn’t find any references to “love” or “romantic love” in the book, even in your index. Isn’t love a major definer of whether one sees herself as “lesbian” or “bisexual”?

I talk a great deal about love in the first three chapters, where my respondents share how they came to see themselves as lesbian, and how they search for romantic partners.

“Invisibility” can be both positive (as in “people can’t be concerned with me and my activities”) or negative (as in “I don’t matter because no one sees me for who I am”). Which attitude makes a lesbian freer to do as she likes? Isn’t there a certain amount of freedom in being an “outlaw” or “on the edge” of society?

I named the book Invisible Families because these are families that live and participate in various aspects of black community life, yet are not recognized as same-sex couple families. They are also part of the LGBT community, but are not visible in that arena either. I do not think of invisibility as a positive thing in the case of these families, because they are not trying to hide who they are. They are not trying to “stay under the radar.” Instead, they want to be active participants in society. They want to be recognized for all parts of their identities. They do not want to be silenced for being gay, or hidden from larger portraits of the LGBT community because they are not white.

While for some it can be freeing to be an outlaw or on the edge of society, black women—by virtue of their race and gender—are not often given a choice in the matter. They/we are often members of the “outgroup,” as psychologists would say. We are placed outside of the mainstream of society, and spend our lives fighting for acceptance and for equal access to all that society has to offer. Operating from this vantage point, it does not feel freeing to be involuntarily regarded as an outsider.

For more information on Dr. Moore’s Rice talk, contact Brian Scott Riedel at riedelbs@rice.edu or log on to http://cswgs.rice.edu.

Kit Van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Houston’s Montrose area. She has published in local, national, and international media.