Mattachine Men

Fighting for gay rights in the ’50s: Two decades before Stonewall, the men of Mattachine stood up.

Playwright Jon Marans’s play, The Temperamentals, about these bold early activists comes to Houston’s Theatre New West in June and July. Marans says the production is about “embracing who you are and not being ashamed. It’s about grabbing life by the balls.”

by Brandon Wolf

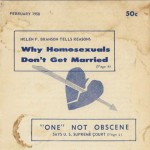

“Gay life in the 1950s was a spy-like world of codes,” says 53-year-old award-winning playwright Jon Marans. “No matter what social situation a gay man found himself in, there was always another level of communication going on if another gay man was present.”

The Temperamentals is not just another gay play; Marans has resurrected an important period in gay history. The critically acclaimed production gets its title from the coded language that was a tapestry of inside jokes. The dictionary defines “temperamental” as “marked by excessive sensitivity.” In 1950s gay code, using this term was a tip-off that a man was gay.

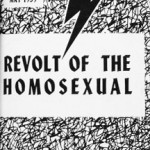

While the Stonewall riots of 1969 were a decidedly significant step forward in the American gay rights movement, nearly two decades before, in 1950, a small group of brave men banded together to form the Mattachine Society, the first enduring gay rights organization in the country.

It Began with a Love Affair

“The Temperamentals is actually the love story of two incredibly strong and independent gay men, Harry Hay and Rudi Gernreich,” says Marans. “The men were not only lovers, but they were the founders of the modern gay rights movement.”

Hay and Gernreich met in July of 1950, when both were living in Los Angeles. At the time, Gernreich was a costume designer in the film industry and was rapidly working his way up the career ladder. Hay had a network of contacts throughout the industry, which he had begun building two decades before as a stunt rider in B movies.

“They were both visionaries,” says Marans. “Hay saw a better world for homosexuals. Rudi saw a new world of fashion design.” Gernreich had escaped from the Nazis in Austria at the age of 16. Many of his close relatives were victims of Hitler’s Holocaust. He knew what happened when a person doesn’t stand up against tyranny.

Hay had been trying for three years to organize gay men who would be dedicated to fighting for their rights. At the 1948 Democratic National Convention, he tried to organize a “Bachelors for Wallace” group. Although he had numerous backers, none of them would put their names on a piece of paper identifying themselves as homosexuals.

“Mattachine probably wouldn’t have happened without Rudi,” says Marans. “Hay had a very abrasive personality and didn’t seem to be aware of just how abrasive he was.” Marans’s research suggests that Gernreich’s legendary charm balanced Hay’s abrasiveness.

Gernreich was also the first person willing to stand alongside Hay and work to convince others to support a gay rights organization. “Rudi was involved in the fashion world, but he was also very political,” says Marans, “and like Hay, he was a political visionary.”

Bringing History to Life

Marans, who now lives in New York City, first became aware of the Mattachine Society when he was commissioned by the San Jose Repertory Theater in 2000 to write a play about Studs Terkel’s book, Coming of Age. That play, Legacy of the Dragonslayers, features vignettes from the lives of numerous human rights activists. One of those activists was Harry Hay. “Every scene in the play that featured Harry stole the show,” Marans remembers.

Fascinated by Hay, Marans read Stuart Timmons’s The Trouble with Harry Hay: Founder of the Modern Gay Movement. The love story captured Marans’s attention, as did the courage and foresight of the Mattachine founders. In 2003, he wrote The Temperamentals and began staging readings at the Brick Theater in Brooklyn. Those readings became popular and continued until 2009, when a Broadway producer/director who liked the play decided to collaborate and stage it off-Broadway. “Getting the play to the stage was a labor of love by countless people,” says Marans.

The first performances in 2009 were staged in a 40-seat theater. Demand for tickets quickly increased, and the play moved to a 99-seat theater. In 2010, The Temperamentals was staged again, this time in a 199-seat theater. The play received critical acclaim, numerous nominations, and three awards.

Audience and Play Become One

Marans takes the first five years of the Mattachine Society as the timeline for his play and weaves that period in the early ’50s into an engrossing theater piece. He creates a dark, brooding atmosphere of fear and paranoia as the curtain rises on the first act. Gernreich and Hay meet for coffee at the Chuckwagon Diner in Los Angeles. Both men are on edge and watchful. In the background lurks a mysterious figure, who could be either another diner or an undercover agent.

Throughout the play, the men worry that one of them has spoken too loudly in public, or that the slightest gesture of affection between lovers will be noticed. They even wonder if their telephones are tapped.

“The more the audience and the play are one, the better,” says Marans. In the first act, they become part of the menacing society of which the men are so fearful. The Mattachine members seem aware that there is a dark world out there that is set against them. At the end of the play, the audience is drawn into an emotional benediction scene using some of the actual words from a concluding ritual that was a part of the early Mattachine Society meetings in the ’50s.

For the benediction scene, “each actor was assigned a specific seat in the audience to go to, and then hold the hand of the person sitting there as the benediction is given,” Marans explains. “Sometimes older gay men whose hands were being held would break into tears. The actors often had trouble delivering their lines because they were so overcome by the emotions of the audience members. I included it because I wanted the audience to feel that they were as much a part of the movement as the people on the stage. When you hear Dale say, ‘You are the brave ones, the pioneers—the first to gather in a public place like this,’ the audience should hopefully feel that he is talking to them. It’s sort of a call to action for everyone to stand up and be counted.”

Reaching for the hands of audience members also held some surprises for the actors. Sometimes the hand they held was a celebrity such as gay playwrights Edward Albee or Larry Kramer, whom Marans had purposely placed in the seats designated for the benediction interplay.

As the play’s run unfolded, Marans quickly noticed that audiences tended to stick around after the show and talk. Most people had been unaware of the Mattachine Society and its place in history, and were amazed at the courage of Dale Jennings. “They wanted more information,” says Marans. So plans were made to offer a weekly “Talk-Out,” an hour-long panel discussion moderated by Marans. The list of speakers he assembled was impressive and included such people as Larry Kramer, Paul Rudnick, David Mixner, Judith Light, and congressman Barney Frank.

The play became a favorite of theater critics, and tickets had to be purchased well in advance. Many celebrities attended the performances—Mart Crowley, Tony Kushner, Michael Feinstein, Terrence McNally, Cynthia Nixon, Dana Delaney, Joan Rivers, Vanessa Williams, and Keir Dullea were all seen in the audience at one time or another. On the evening that his parents attended, Marans made sure they were seated next to guest Bernadette Peters.

Life after Mattachine

The Hay-Gernreich romance ended in 1952, and Gernreich went on to become a prominent American fashion designer. His fame landed him on the cover of Time magazine in 1967, and he was invited to play a guest role on the Batman TV series. Gernreich favored a futuristic look and his designs were unique, daring, and controversial. He is probably best known for his monokini, a topless bikini.

Gernreich was a lifelong advocate of nudism, so it’s not surprising that the thong swimsuit was another of his creations. Just days before his death from cancer in 1985, he unveiled his last creation, the pubikini. (Readers are left to determine for themselves what made that swimsuit unique.) Today, samples of his famous designs are in museums throughout the world.

Following his break with Gernreich, Hay became romantically involved with a young Danish immigrant named Jorn Kamgren, and they were partners for 11 years. Although forced out of the very organization he had founded, Hay continued to keep in touch with many gay activists. He had a brief affair with activist Jim Kepner before meeting John Burnside, who would be his partner for the rest of his life.

Hay found himself disappointed with gay activists in general, and remained an anti-assimilationist to the end. He was wary of minorities discarding their unique attributes in favor of adopting the cultural traits of the majority for the purpose of societal acceptance. During the first 10 years after Stonewall, he loudly criticized gay activists for marginalizing drag queens and leather enthusiasts.

In 1979, Hay and Burnside founded the Radical Faeries, a group that still exists as a loosely affiliated worldwide network of people seeking to reject hetero-imitation and redefine queer identity through spirituality. Hay stayed active in the group until his death from lung cancer in 2002 at the age of 90.

__________________________________

The Birth of the Mattachine Society

Gay activist Harry Hay says he became interested in gay rights after reading John Carpenter’s The Intermediate Sex. He had been attempting to form a gay political action group for several years when he met Rudi Gernreich, who was titillated by Hay’s bold ideas. When Gernreich read Hay’s manifesto, which Hay named The Call, Gernreich said it was “the most dangerous thing I had ever seen.” Hay and Gernreich convinced their friend Bob Hull and his ex-lover, Chuck Rowland, to join them in their daring venture. On November 11, 1950, the first meeting of the International Bachelors Fraternal Order for Peace and Social Dignity was held. On that evening, a fifth gay man joined the group: Dale Jennings, Hull’s current lover.

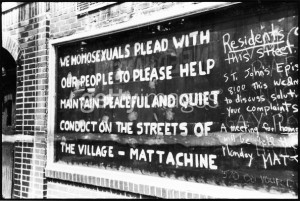

The group soon changed its name to the Mattachine Society, after the Société Mattachine, a French medieval and renaissance masque group that was a secret fraternity of unmarried men. The Frenchmen were known for their protests against peasant oppression, during which they wore masks to hide their identities.

In Jonathan Katz’s Gay American History, Hay is quoted as saying, “So we took the name Mattachine because we felt that we 1950s gays were also a masked people, unknown and anonymous, who might become engaged in morale-building and helping ourselves and others, through struggle, to move toward total redress and change.”

The name held other appropriate symbolism as well. The Mattachines had taken their name from a character in Italian theater known as Mattaccino—a masked court jester who dared to speak truth to the king.

Katz’s History reports that the group’s goals were to “unify homosexuals isolated from their own kind,” to “educate homosexuals and heterosexuals toward an ethical homosexual culture paralleling the cultures of the Negro, Mexican, and Jewish peoples,” to “lead the more socially conscious homosexual to provide leadership to the whole mass of social deviates,” and to “assist gays who are victimized daily as a result of oppression.”

The group began to slowly grow as word of it spread throughout California. Then in 1952, they finally got the breakthrough they needed to rapidly increase their membership when Jennings was arrested on a charge of public lewdness by an undercover agent who came on to him.

At the time, the common response to such an incident was to plead guilty and pay a fine. But even this strategy was less than foolproof. Arresting police often blackmailed those who were arrested, threatening to reveal their identities as gay men.

In court, Jennings admitted that he was homosexual but denied any wrongdoing. The case ended with a hung jury—11 voting not guilty and one holdout. The judge dismissed the case, and the prosecution did not pursue a second trial. Although the media ignored the case, Jennings became the poster boy for gay resistance among Mattachine members.

In court, Jennings admitted that he was homosexual but denied any wrongdoing. The case ended with a hung jury—11 voting not guilty and one holdout. The judge dismissed the case, and the prosecution did not pursue a second trial. Although the media ignored the case, Jennings became the poster boy for gay resistance among Mattachine members.

In May of 1953, the five original founders—who had varying degrees of affiliation with the American Communist Party—were forced to resign. Mattachine existed as a single national organization headquartered first in Los Angeles and then, beginning around 1956, in San Francisco. Chapters were also established in New York, Washington DC, Chicago, and other locales.

After founding the Mattachine Society, Hay often traveled to visit with other groups of gays. “Sometimes people would come up to me and whisper, ‘Thank you for giving me my life,’” Hay would write later. “But my favorite was when someone whispered in my ear, ‘You are our hope upon the wind.’”

Due to internal disagreements, the national organization disbanded in 1961. The San Francisco chapter retained the name “Mattachine Society” while the New York chapter became “Mattachine Society of New York, Inc.” Other independent groups using the name Mattachine were formed in Washington DC in 1961 and in Chicago in 1965.

In 1966, the New York State Liquor Authority’s rule that ordered bars not to serve liquor to the disorderly was applied to homosexuals, who were considered by their very nature to be disorderly. Gay men were often evicted from bars or directed not to face other customers. In April of 1966, a “Sip-In” was held at the Julius Bar in Greenwich Village—a deliberate attempt to challenge the rule.

Before ordering a drink, New York Mattachine members read a statement: “We are homosexuals. We are orderly, we intend to remain orderly, and we are asking for service.” The next day the New York Times ran the headline, “Three Deviates Invite Exclusion by Bars.”

As a result of a Mattachine challenge, the courts ruled that gays had a right to peaceful assembly. In 1967, the Stonewall Inn opened a block southwest of Julius.

Following the 1969 Stonewall riots, a new generation of gay leaders felt the need to endorse a larger and more radical agenda to address oppression. Mattachine began to be increasingly seen as too traditional and not willing enough to be confrontational. Several regional entities that went under the name Mattachine eventually lost support or fell prey to internal division. Eventually, the New York group closed due to impending bankruptcy and was disbanded in January of 1987.

It was an ironic end for the organization that began at a time when incredible courage was necessary to confront the bigotry against homosexuals—and whose founders were considered so radical that they were ousted from their own organization in 1953.

Brandon Wolf is a frequent contributor to OutSmart magazine.

______________________________

Theatre New West’s Houston

Production of

The Temperamentals

by Jon Marans

Directed by Joe Watts

When: June 16–July 16

• Benefit/opening performance, Thursday,

June 16, for Houston GLBT

Community Center, 7:30 p.m.

• Friday and Saturday performances at 8 p.m.

• Friday, June 24—Pride performance at 8 p.m.

• No performance on Saturday, June 25

• Sunday, July 10, matinee at 2 p.m.

• Thursdays, July 7 & 14, 7:30 p.m.

Where: Dowling Music, 2615 Southwest Frwy.

Tickets: Opening, Fridays, and Saturdays $25; seniors 62+ and students with ID $20;

Thursdays, July 7 & 14, all tickets $20; Sunday, July 10, all tickets $20.

Reservations: 713/522-2204

Info: theatrenewwest.com

______________________________

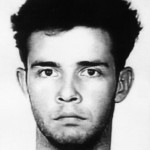

SIDEBAR:

1950s Houston

Houston’s own pioneer gay activist Ray Hill (pictured) was in high school in the 1950s. Hill says there was no organized effort in Houston to fight for gay rights, and no Houston affiliate of the Mattachine Society. However, Hill does remember being a student at the University of Houston in the late 1950s: “When the guards left a brick in the back door of the library so they could use the bathroom, I would sneak up into the closed stacks and read copies of the Mattachine Review.” —B.W.

__________________________________

Playwright Jon Marans

The talented gay man who wrote The Temperamentals grew up in Silver Spring, Maryland, where he played Charlie Brown in junior high school. He also worked in the school library. “I saw some books about gays,” says Marans, “and I knew I couldn’t check them out. So I smuggled them out of the library, read them, and smuggled them back in.”

Marans graduated from Duke University with a major in mathematics and a minor in music. In college, he directed the campus production of Gypsy. After college, he moved to New York City and immersed himself in the field of entertainment. He started out as a singing waiter in an Italian restaurant in Englewood, New Jersey, which was run by two gay men.

Over the years, he held various jobs—as a screenplay reader for Michael Douglas Productions, a senior editor for Us magazine, and a member of The Carol Burnett Show writing team. In 1996, he wrote Old Wicked Songs, which became a Pulitzer finalist and has been performed in more than 20 countries. —B.W.