The Hidden Spirituality of Men

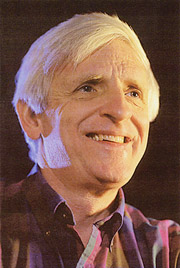

A Conversation with Matthew Fox.

By Blase DiStefano

Among the several reasons Matthew Fox was given for his expulsion from the Catholic Dominican Order in 1992 was that he failed to condemn homosexuality. His 28 books, particularly Original Blessing (1983) and The Coming of the Cosmic Christ (1988), describe his philosophy that he has named Creation Spirituality. This alternative Christian spiritual system includes, among its several concerns, diversity, ecumenism, and ecological justice. Fox spoke with OutSmart about his struggles with the church, gender justice, gay heroes, and his new book, The Hidden Spirituality of Men (New World Library).

Blase DiStefano: The first thing I want to hear about is the year of silence imposed on you by Cardinal Ratzinger [now Pope Benedict XVI].

Matthew Fox: They silenced me for a year, as they did the Franciscan theologian Leonardo Boff in Brazil. So I was forbidden to teach or lecture or preach.

Why did they do that?

They’re very threatened by my teaching about Original Blessing instead of Original Sin, the emphasis I put on issues of gender justice and how the Catholic Church does not allow women to be in positions of leadership and so forth. After I did the year of silence, I came back for a couple more years, and then they kicked me out of the Dominican Order altogether.

They had a list of objections. One, that I’m a feminist theologian. Two, that I call God “Mother,” as do the medieval mystics—it’s in the tradition. Three, they said there’s no blessing to Original Sin. But all scholars agree that Original Sin is not in the Bible; it’s not a Jewish concept and Jesus was a Jew, so isn’t that strange that the Western Christian Church put so much emphasis on Original Sin when Jesus never heard of the concept in his life? Four, they said I was working too closely with Native Americans. And five, of course, I don’t condemn homosexuals.

The fact that I’m gay and was brought up Catholic was why I wanted to ask you about that; I had a feeling that was part of what was involved. And they are so patriarchal.

They are so threatened by women and gays and scientists…

And that man is now the pope.

That man [laughs]. That’s true. And what’s even worse is that man is busy courting Opus Dei. He expelled me from the Dominican Order, Leonardo Boff from the Franciscans, and the devoted Eugen Drewermann in Europe was expelled from the priesthood. So the three of us got knocked out the same year—downsizing of thinking in the Catholic Church. This pope has silenced over 110 theologians. I’m just one of them.

That’s why the pedophile crisis happened, because they dumbed down the church and they appointed bishops and cardinals who, instead of having a conscience and intelligence, were yes men. So you have these people passing pedophile priests from parish to parish and diocese to diocese, and they weren’t punished for it. One of them, Cardinal [Bernard Francis] Law, was given a reward, and he’s now running a fourth-century basilica in Rome. He’s the worst of the lot. He should be in jail.

These men, they need help.

[Laughs] You’re right. They need journalists blowing some whistles. I’ll be honest, in great part, the mainstream media in America is afraid to take on the Vatican.

They are, and it’s a shame. And speaking of shame, in your book you say, “Homosexual men are often more mature than heterosexual men because they had to deal with that shame—and they either die of it, going the way of addiction, or they go beyond it, beyond the norm of what is shameful and isn’t shameful for a male.” So what if I’m homosexual—and not dead—but also have an addiction, whether it be to sex or alcohol or food. Am I likely still in that shame mode?

First of all, all human beings have the potential for addictions, and health is not about not having addictions, it’s about not letting them run our lives. So I wouldn’t draw a lot of conclusions.

How does one deal with that addiction then?

The old one-day-at-a-time. I think you have to balance addiction, if you will, with spiritual practice, meditation, running, exercise, focusing, chanting, sweat lodges—there are many spiritual practices that can jerk us, if you will, into being more focused, intentional, and healthy. We have to realize, in our culture, when it comes to addictions, we’re up against these big forces that want us to be addicted. Consumer culture wants us to be buying more booze, more drugs, more food, and go on more shopping sprees. Look how even the restaurant business can stuff us instead of feed us.

It’s really the fifth chakra [throat chakra] that needs attention, because of the gluttony. I think consumer-based economics is trying to make us all addicted to buying things, and it’s today’s form of the capital sin of gluttony. It’s about stuffing things down our throats, as opposed to giving birth to our ideas, the throat as a birth canal. That’s why creativity and generativity are such healthy medicines against addiction, because in giving birth to your wisdom and putting it in the world—whether it’s through theater or journalism or politics or singing or dancing or what have you—I think this is the antidote.

You have to get yourself off of your butt.

[Laughs] That’s right, and that’s what this whole book is about: getting men off of the couches, out of our couch potato-itis and getting into our strength. That’s another thing. What do we stand up for? Where is our warriorhood? Are we defending the earth? That’s a full-time job. We don’t have the time for a lot of side addictions, if we’re really committed to a noble and worthy cause.

Assuming that all of these addictions are basically distractions from taking a hard look at ourselves, overcoming them may be a little difficult.

[Laughs] That’s right. It’s a cover-up of our deepest passions of both joy and of grief. And, again, doing rituals that get you into grief-making, and rituals that allow your joy, celebratory rituals. This is where dance comes in and so forth; this is a healing path.

So many people may be turned off when you say the word “ritual.” Is there a way to get past what people may think of what a ritual is and what it would entail?

When the pope fired me, I became an Episcopalian priest in order to work with young people, young Anglicans in Sheffield, England, who were re-inventing worship using raves and dance, and that’s what I’ve been doing for the last 10 years. We’ve put out about 90 what we call “cosmic masses,” where instead of sitting and being read to and being preached at, we’re dancing, and it culminates with communion. We have projections with slides and stories, and the theme of the mass—for example, if the mass is Return of the Goddess, we have maybe 500 slides of the Goddess from all the world’s traditions including Christianity, and we dance in the context of these slides and wonderful images, therefore bringing them as a meditation into our bodies, while dancing to very good music, and it really works. This is an ancient way, and ceremony is the ancient way to pray, to bring your body into it, to get into something deep. People go into these states all the time. I remember a young man, he was like 21, said, “For the last five years, I’ve been going to raves every weekend. What I’ve experienced tonight is what I’ve been looking for in raves. I’ve experienced deep prayer, a sense of community, beauty, and real peace. What’s different here than in a rave is here you have multiple generations represented. In a rave it’s usually just one generation.”

I believe the young people of the world have come up with this post-modern form of celebration, which is rave. It’s very powerful, very ancient, and it’s really very pre-modern, the idea that you go into an altered state by dancing. It’s our job as elders to bring this into liturgical traditions to rev them up and make them interesting and alive again. I’ve been doing that, and we’ve had some positive results.

Can you talk about the connection between sexual power and spirituality?

Obviously, in the Eastern tradition sexuality is one of our chakras [second chakra]. A chakra is a gathering place of energy. It’s a place from which we tap into our power and love. There are temples all over India that honor the phallus, and also the vagina, so there’s an integration of the sacredness of sexuality and what is sacred. The same is true in Africa. Even in Muslim areas, there are huts built in the shape of phalluses where young men gather and learn what it means to be a man. And then in the West in the Hebrew Bible, we have—big surprise—Song of Songs, a celebration of sexuality and theophany.

We don’t hear about that very much.

The church has been trying to clean it up. They always say it’s really about God loving Jesus and Jesus loving your soul and God loving the church, but ask any Jew what it’s about—it’s about lovemaking as a redemption in the Garden of Eden. These are in the tradition, but they’ve been banished. I quote a Thai master in that chapter, “More people have mystical experiences making love than they do in church.” [Both laugh] I think that’s a pretty astute observation.

I don’t think the church really wants to advertise that.

[Laughs] That would be why the church is so preoccupied with sex. Maybe it sees sex as the greatest competition. The fact is that a healthy person integrates all his or her chakras. It’s about honoring the chakras. These are power centers. We have the power of sexuality. It’s a power and, like any power, what are you going to do with it? Are you gonna use it for love’s sake and beauty’s sake and play and celebration and joy, or are you gonna use it as a weapon, which is obviously what something like rape is or beating up on sexual minorities, using sexuality as a weapon….

With a lot of men, both gay and straight, upon meeting somebody, there’s a tendency to relate to only the physical beauty of the person. How does one get past that initial reaction?

As years go on, you get past it, in a way, because you see yourself aging and you see others of your generation aging. You can still honor and appreciate the beauty of a younger person, but you also learn in life where the deepest beauty is and what beauty really lasts. Obviously everything in life, as the Buddhists say, is impermanent, including our physical bodies and our physical health, so it’s not a question of loving the body less but of loving other dimensions more. For example, think about the beauty of a symphony or the beauty of a play or the beauty of last night [November 4, 2008]—Obama was elected—and having an intelligent human representing you. I think a lot of the tears we saw last night and shed ourselves were tears of beauty.

Beauty is not, again, about running away from the beauty of young people’s bodies, whether they’re gay, straight, male, female, it’s about incorporating, expanding our life around beauty. The ancients, the pre-moderns talked about God as beauty. Thomas Aquinas said, “God is the most beautiful thing in the world and all things participate in the divine beauty.” So beauty is a name for divinity, and it’s a question of incorporating, I think, the moments we have with beauty into a larger context—the beauty of the planet, the beauty of the universe. This is what drives people.

Aquinas has a brilliant passage about the sin of acedia, which is really about couch potato-itis. It’s when people lack energy to begin new things. It’s this passivity or cynicism or depression or despair, and he says the medicine for acedia is zeal. Zeal is the opposite of acedia. Zeal comes from intense experience of the beauty of things. That is so powerful that beauty is so important for us. It’s about falling in love, isn’t it? Beauty is what gives us the energy to carry on. That brings out the warrior in you: to defend what you cherish and what you feel is beautiful. But we can get stuck. Beauty, like anything else, is good, but we can get addicted to the physical beauty of people. But again, I say, it’s not about loving beauty less but about expanding it and going deeper. It’s not about loving a beautiful body—there’s a heart in there, a soul, a mind.

Often, first impressions are like, “Oh, he’s hot.”

You go deeper. What does that mean, “Oh, he’s hot”? You’re looking at that person as an object alone. Every person is more worthy than just being an object, and that’s where love wants to drive you to know more about the individual. Know more about the person as a person, not just as a hot object.

What would be the benefits of a straight man overcoming his fear of homosexuals?

We both have a lot to learn from each other, so it’s a learning process. Gay men have been through a lot and they’ve suffered a lot, especially around issues that are men’s issues, such as shame and aggression.

How do we deal with aggression?

A lot of gay men have found that art is a great way to deal with aggression. I like to tell the story of Michelangelo when he was painting the Sistine Chapel. Originally he had all these figures that were naked, and there was a crotchety old cardinal who comes in and says, “You can’t paint these guys naked, you have to paint loincloths on them ’cause the pope prays here.” Michelangelo says, “Go away, get out of here. I’m the artist here.” So the cardinal goes to the pope and complains, and the pope tells Michelangelo he has to put loincloths on these people. Michelangelo was very upset, so when he painted hell, he put this cardinal in hell. When the cardinal saw that, he went and complained to the pope again, and the pope said, “I’m sorry. If he had put you in purgatory, I might have been able to do something about that, but not hell.” To this day the cardinal is in hell in the Sistine Chapel, so who won the argument? Michelangelo used his gifts as an artist to express his outrage.

That’s wonderful.

It’s better than beating the guy up, and it lasted much longer. [Both laugh]

You discuss 10 archetypes to awaken our spirituality. For those who might not be into this, can you give me an example of one and how to access it?

As far as accessing it, I have the appendix where I have about 10 exercises for each of the 10 archetypes that you can do, so there are practices to help people get into this.

Let’s just pick the one of the Green Man. I think the Green Man is extremely relevant to our moment in history. The Green Man is ancient and pagan and pre-Christian, but Christianity adapted it in the 12th century. It came in with the Goddess, who came in strong in the 12th century. The Green Man is pictured with tree limbs coming out of his mouth and the fifth chakra. His beard is made of leaves, so it’s honoring our sexuality but in context of our generativity of nature itself. The Green Man is about our deep relationship to nature, the plant world, but also the animal world, because without plants there would be no animals.

In the Native American tradition the plants are the wisest creatures on the planet, because they invented photosynthesis and learned how to eat the sun. Without them we wouldn’t be here.

So the Green Man is also about being a tree, standing up straight and having deep roots, being a warrior—there’s a warrior dimension there, defending Mother Earth. Like any living archetype, there’s a lot of energy there to excite men to be men. You can be a Green Man whether you are gay or straight. And this time in history, what is more pertinent? Because we’re literally destroying Mother Earth and our own nest with global warming and everything else we’re doing. So every person has to be a Green Man in some way at this time in history. I think the Green Man is an archetype that really feeds our moral and political imagination today.

The archetypes are supposed to prepare us for a Sacred Marriage. What is Sacred Marriage?

I see the Sacred Marriage as the union of the masculine and the feminine. Especially the Divine Feminine and the Sacred Masculine. The course of the whole book is that women have been working on their spiritual development and awakening in a more conscious way than men have for the last 40 years. Men are behind and need to catch up in order to be a partnership. Now the Sacred Marriage—we’re talking metaphors here, too—it’s not just about man marrying woman. It’s about any relationship whether it be man to man, woman to woman, or man to woman. These dynamics of the masculine and the feminine and the Sacred Masculine and the Divine Feminine, they come into play. The right brain and the left brain, the yin and the yang, the water and the fire—all relationships involve them because each individual is playing with these elements in himself or herself, so a healthy relationship of any kind has at least four or five dimensions going on. There’s a masculine and a feminine in me, there’s a masculine and a feminine in you, or whatever partner, and then there’s the relationship itself, which is a whole new work of art. But it’s based on the dynamics of the individuals. So that’s why life isn’t simple. It’s a little complex. Relationships are complex.

Now with the new president, I wanted to talk about the Black Madonna. Can you tell me a little bit about her?

In the two chapters I have about the Sacred Marriage, one of them proposes that we needed this time in history, a marriage between the Black Madonna and the Green Man. The Black Madonna comes from Africa, as we all do, and she’s an ancient Goddess who came into Christianity early. There’s one temple from the third century, in Sicily, that is a temple to the Black Madonna, but she’s spread all over Europe. You find statues to her in Spain, France, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Russia, Switzerland, Germany, Italy, of course, so she got all over the place.

What does she represent?

She obviously represents people of color, and she represents the Earth, because the Earth is dark. She represents grief, but she also represents a celebration of life. In India, kali means black, so she’s present in the Hindu tradition there, and of course Our Lady of the Guadalupe, so important to many Latino people and she’s a brown Madonna. She was really powerful in the 12th century, the same time the Green Man was, and she’s having a comeback today. She has a headdress that has a rattle in it, and I think part of her job is to rattle us, to wake us up, that prophetic spirit of shaking us up. I think she represents a lot of the needs we have today as a species to get more grounded, to love the Earth more. And there’s a cosmic dimension to this—she’s a cosmic mother, and now science is telling us that the universe is mostly black holes and dark matter, so that’s a feed-in to the metaphor of the Black Madonna of the black cosmic mother.

Since there’s all this talk about gay marriage, talk about the gay/straight wedding in your book.

When tribes are healthy enough in their own skin and their own traditions and their own stories, instead of having to denounce each other or sit at opposite ends of the room, we should be mixing and learning from each other, because diversity is obviously what nature is biased about. Instead of blaming homosexuals for the failure of heterosexual marriages, which is what one wing of crackpot Christianity wants to do, I think it might be appropriate to celebrate gay marriages, and then see what gay marriages have to teach heterosexual marriages. It might be there will be a lot that both can learn. I think I go through a list of lessons to be learned from gay people, including the commitment to creativity and beauty and art, which is really in every man but is often stifled. With the younger generation I just see this all the time—they’re not hung up on homophobia.

There are heroes of the gay movement in the last 30 years who, just like King paved the way for Barack Obama, took real courageous stands decades ago that have made this possible for this generation.

So I want to know, how did you become so gay-friendly?

[Laughs] I suppose part of it was being a feminist. I was teaching in the early ’70s in a women’s college for four years outside Chicago, and hearing women’s stories made me a feminist. It’s hearing people’s stories and recognizing the beauty of people, and I found a lot of beauty in these women and, of course, some of them were lesbians, and they had stories to tell. It’s about realizing what tremendous contributions gay people have made in history and knowing there’s nothing inferior going on here, there’s something special going on here.

Blase DiStefano also interviewed Scott Turner Schofield (“Girly Man?”) for this February 2009 issue of OutSmart magazine.