Gone Missing

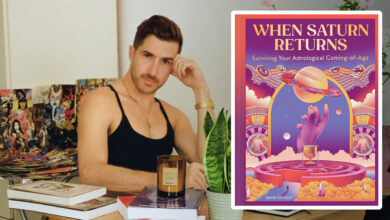

‘Mysterious Skin’ author Scott Heim follows up with a new novel, ‘We Disappear.’

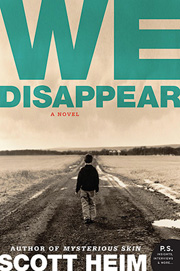

We Disappear

is the apropos title for Scott Heim’s new novel, the first book from the openly gay author in 11 years. Best known for his 1995 debut novel, Mysterious Skin—adapted into the acclaimed, daring 2005 film by director Gregg Araki—Heim’s latest fiction tome follows his sophomore effort, In Awe, published in 1997.

The tale of Scott, a drug-addicted New York writer whose cancer-stricken mother, Donna, becomes obsessed with missing children, We Disappear (HarperCollins) is a fine return to form and pet themes—of buried and obscured memories, of lost youth, of self-destructive behavior—for the Kansas-raised, Boston-based Heim (www.heim.etherweave.com). By phone, we discussed his disappearance, the book’s blurring of fact and fiction, and online predators.

Lawrence Ferber: Why has this book been such a long time coming?

Scott Heim: Well, where to start? I think after my second book came out, I got disillusioned with publishing in general. A lot of my friends were losing their book contracts. Publishing changed a lot, and it didn’t seem they were invested in their authors as much if you weren’t making them a zillion dollars.

I started writing We Disappear, although it existed in a different form. I went to London and did this teaching gig, and when back, I started freelance work [for school textbooks]. I went through serious depression problems and doing drugs, but certainly not as much as the character [of Scott] in the book. The thing about having a drug problem is you think it’s going to make you creative or more exciting, and it doesn’t. And if you’re depressed already, it only fuels that depression. My boyfriend and I started having problems. My mom was dying. Finally in 2002 or so, more uplifting, positive things happened in my life. I moved to Boston and started working on the book again. [My boyfriend] Michael and I were going strong again. But there were a number of years where it felt like everything was at a standstill.

I started writing We Disappear, although it existed in a different form. I went to London and did this teaching gig, and when back, I started freelance work [for school textbooks]. I went through serious depression problems and doing drugs, but certainly not as much as the character [of Scott] in the book. The thing about having a drug problem is you think it’s going to make you creative or more exciting, and it doesn’t. And if you’re depressed already, it only fuels that depression. My boyfriend and I started having problems. My mom was dying. Finally in 2002 or so, more uplifting, positive things happened in my life. I moved to Boston and started working on the book again. [My boyfriend] Michael and I were going strong again. But there were a number of years where it felt like everything was at a standstill.

You actually named the characters after yourself and your mother, Donna. Talk about thinly veiled portraits! Talk about this decision.

I worked on the book so long, I wasn’t excited about it anymore. As I revised, I realized it was easier and I felt more drive or inspiration to write the characters more like us. My mom died similar to the way it happens in the book. When I went home to Kansas to take care of her, I knew she didn’t have long to live. There was a lot about her life I still wanted to know more about, so creating all this fiction about her childhood and life was my substitute for the time I thought we were going to have before she died. It sounds very Dr. Phil to say it was part of the healing process, but it helped me come to terms with what was happening—channeling that energy into creative work got me through that period a lot easier. So I took this whole fictional thing and blended this memoir portion, and it completely jump-started the book for me again.

So it could be called a fictoir ?

Yeah. You’re not the first person to say that to me. I did this writing workshop fellowship thing in Minneapolis at this place called The Loft, and this woman said the same thing. Maybe I should have them change the book cover and put that on it instead of novel.

As the book cover gives away in its synopsis, Scott discovers a boy named Otis handcuffed in a secret basement room. Where did Otis come from?

It’s funny. I think at some point I wanted there to be a blur between what was actually happening—realistic fiction—and the fiction that generates from an unreliable narrator. That’s one of the tricks of the book—the narrator and the other lead character are unreliable in a way. She’s dying and losing her mind, and he’s so screwed up with drugs and all that. I wanted Otis to represent something physical and real for some readers, but he is also a representation of the narrator’s childhood and this past he can no longer reclaim. And I love playing with ghost stories and psychological thrillers. I wanted an element of that also.

What is it about abused or abducted kids that you find so interesting?

I don’t know. You just have your obsessions and don’t realize until someone says, in all three books you’ve done this. I realize all my favorite writers have their own obsessions. You can pick up anything and read a paragraph and say, this is Flannery O’Connor or Dennis Cooper. It’s not like they write the same book over and over, but they have their thing. I guess it was something I always was obsessed with. My mom and I [were both] obsessed. There was some kid missing in my town, and I remember my mom collecting articles and newspaper clippings about him. I started reading early, and the idea excited my parents—whatever I was interested in they would foster. Instead of The Wizard of Oz, they would bring home true-crime books that I would read at seven years old.

Do you watch MSNBC’s To Catch a Predator series, where they entrap adults who think they’re hooking up with someone underage online?

You know, that is one of my hugest pet peeves. It’s total entrapment, and I hate how there’s this idea that’s going to make someone better. The way to rehabilitate them is not to humiliate them and ruin their lives on national TV. I hate how the host and producers act holier than thou, as if they don’t have any skeletons in their closets.

So what’s your dream cast for the movie version?

That’s a tough one. Weird. I don’t know that I thought about it that much. Since the book is so close to home and I used the same names, when I saw the book in my head it felt like I was writing a memoir in some ways. I doubt it will ever be a movie. I’m still amazed Mysterious Skin was made.

Lawrence Ferber profiled director Kimberly Peirce and her movie Stop-Loss for the April OutSmart.