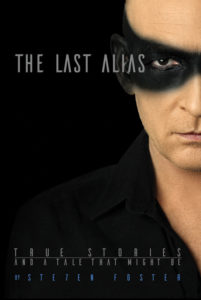

Gay Houston Author Confronts His True ‘Selves’

Ste7en Foster comes to terms with his different personas in 'The Last Alias.'

After a rich career as a writer and director in the world of anime, Houstonian multi-hyphenate Ste7en Foster has created a new universe of expressive, archetypal characters—and they’re all in his head. In his debut memoir The Last Alias, Foster explores 22 distinct personas from within: “The Survivor,” “The Fool,” “The Freak of Nature,” “The Sexual Carnivore,” and many more. In the process, he examines painful episodes involving mental health, gay identity, and familial strife while casting off hang-ups about sexuality and expression and embarking on a new path of self (or perhaps selves) awareness. OutSmart spoke with Foster about his long path to The Last Alias.

David Goldberg: What was the genesis of this memoir?

David Goldberg: What was the genesis of this memoir?

Ste7en Foster: About four years ago, after I left my anime career, I had what Lemony Snicket would call “a series of unfortunate events.” That’s what shook my world up. It was a breakdown, and I had to figure out what my new world looked like by looking at the old world.

How did you come to these “selves” that you explore in the book?

These were the stories that wouldn’t let go; the stories that needed to be told. I was in a time of self-examination and self-discovery, and I wound up looking at how one story set off the other, and one dovetailed into the other. I just followed the stories where they led me, and they helped me find out who I was as a person again.

When did you feel like you were ready to start assembling and sharing these stories?

I thought that if I could help just one person, and [even if it’s] only one person, then it will make all that I went through a little bit easier to swallow. Because if that’s not the case, I’m left with “God’s a dick,” and I don’t want to believe that. So I thought that maybe if I tell these stories, they could help people accept or understand parts of themselves more, or go through what I went through more easily, or let their family know what they were going through. I had to swallow my own ego and just be honest about [my experiences]. There were stories I wish weren’t in the book for that reason, but if I was going to be honest, I had to put them in.

What was the hardest part about writing this book?

You’re asking questions that I should know the answers to. It was an organic thing; I was doing this because I didn’t know what else to do. I wrote these stories, and then they kind of formed a structure in memoir. I could then see that this could be something like Sloane Crosby, or Samantha Irby, or Michael Arceneaux, or something like that. I did that same kind of structure, but I was maybe a little more vulnerable.

When you were discovering these different aspects of yourself, did you go through a sort of “coming out” process? Did this book help you introduce these versions of you to the world?

There were parts of myself that I didn’t like admitting [were there]. It’s universal, but I’ve been able to put it into words: I think we’re all incredibly critical of ourselves, to [our own] detriment. Especially gay people. That’s what I liked about the book. If anybody knows about showing only certain sides of ourselves and “acting out” as a character, it’s gay people. If we put a spotlight on this persona, then we’re good. But we can’t show [straight people] that persona, because they wouldn’t handle that. And you just have to be able to focus on all of it, and admit to all of your selves. I had to look at whether I’m a good father or not. A lot of people would look at my life and think I’m a terrible father, and other people may think I’m a good father. I just feel that if you’re gay, it’s harder for you to know yourself in terms of how the rest of the world sees you. We can’t separate the gay part of ourselves from any other part. It’s not conceivable. It’s who we are, just like how we can’t change any other thing about us. When we expose our real selves to the outside world, being open and honest about who we are, it’s then judged, and [that judgment is] based on an outside point of view. We don’t get to stand on our own and go, “This is me! Here I am!” It’s got to be subjected to the world’s mores and morals, and the world’s point of view. Gay people don’t get to say “free to be, you and me” like the rest of the world does. [The world doesn’t judge being] straight like they judge being gay. If you want to have a family, they don’t judge that part of you. But if you’re gay, they say that you might not be fit to have kids. We’re just different.

Did going through this process of confronting your different selves lead you to confront any moral hang-ups or judgments you had about yourself? Did you get to reclaim any aspect of yourself that society may have deemed “unfit?”

I had to look at myself really honestly, and that was good and bad. I looked at myself and realized that I’m more of a hero than I ever thought I was. I never thought of myself as a brave person, or someone who would go to battle. But I am that person! Sexually, I had to ask myself: Is this dysfunction, or is this what I like? I remember I got into a fight with a therapist. She was trying to say that sex doesn’t define us, and I said it doesn’t define us but it’s a very big part of who we are. Maybe I’m talking about men more, but not in blanket terms. But we’re driven by sex—sex interests us, sex propels us. And we have so many more hang-ups about that, because from our first sexual inkling on, we were branded “bad.” If you’re straight, you don’t get that. You want to play house with Susie next door, and that’s totally fine, and everyone is cool with it. But if you want to do that with Billy next door, you find out that that’s not really cool, and that’s not what it’s supposed to be. That’s your first introduction to it as a child: expressing yourself is bad. And [it’s the same for] our first sexual experience, or our first romantic experience. We’re told that our very nature, and the very thing we’re driven to, our very desire, is wrong, and we’re wrong. We have to fight that the whole rest of the way, which means that it magnifies every little kink we have. Do we accept it? Do we embrace it? Does it make us more ourselves?

What’s intriguing about your book is this exploration of who you really are, beyond ”gay white man.”

Society puts these personas on us. But in my view, being reductive helped me focus on aspects of myself that were a blur to me. Everything was a confusion. Who I was was this jumble of people, like a crowd at a concert. I had to look at each of them and say “You’re this guy, you have these strengths, but you don’t cover this part of me.” Then I’d look at another part and go “This is you as this person, but you’re not that side of me. That’s not you.” Who was the all-encompassing me? For me to look inside wound up being a good thing, because I was able to categorize who I was at various times, and which personas I used in various situations, to find out which of them, if any, was the real me. I think we show fragments of ourselves, because that’s easier for us. Very few of us know who the real person is, behind it all. We all get to the point where you look in the mirror, and if you’re really intuitive, you look at that person and you don’t know who is looking back at you.

Are there any sides of you that were previously hidden and now get to be embraced and brought into the world?

Yes! It’s often the uncomfortable parts that I need to embrace—parts of myself that I’m not proud of. Why is that? That’s old culture, and all these old religious or sexual mores putting themselves on me that I’m still constricted by. The challenge is to embrace that part of me. The part that is… well, who I am. There’s a story about sex in the book, and I put a warning on it saying the story is very sexually graphic and uses sensitive language that may not be appropriate. There are very graphic sex scenes, and it’s almost up to the reader to decideif this is positive, or negative. Is this his f–ked-up sexuality, or is this his romanticism? I left that up to the reader to decide.

It sounds like it comes down to reclamation.

It was about analyzing who I was—accepting the good parts and the bad parts, and embracing them both. With the ones that were poisonous, I need to know that I can keep a closer rein on them and not let them take over, which is what they’re likely to do. There’s one called “The Punisher,” and he’s always willing to take the lead. And the fact that I’m aware of that now gives me power over it. Then I can go forward and be stronger and not so critical, and I can shine that light on those parts of me. It’s like knowing the bad parts of you is what gives you power over them, so you can control them more. And then the good stuff can come in. It blows you away, and you’re like, “Holy shit, I didn’t think I was this good of a guy, and I am. It’s amazing.”

The Last Alias by Ste7en Foster is available now on Amazon.com.