Moving Pictures

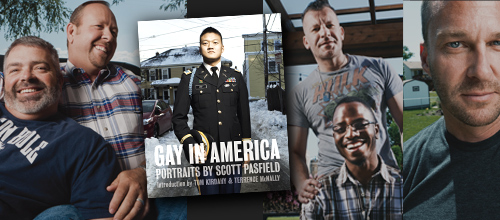

Photographer Scott Pasfield turned his lens from high-paying editorial commissions and instead focused on the U.S. of Gay. The result is a richly composed collection of images that creates a sprawling, often surprising portrait of what it looks like to be a gay man in America.

Photographer Scott Pasfield turned his lens from high-paying editorial commissions and instead focused on the U.S. of Gay. The result is a richly composed collection of images that creates a sprawling, often surprising portrait of what it looks like to be a gay man in America.

by Steven Foster

Photography by Scott Pasfield

There are no sequined drag queens gliding along parade floats festooned with rainbow balloons. No smoke-haloed Tom of Finland leather daddies clenching half-ashed cigars in their teeth. There is not one chiaroscuro nude soccer player posing in a steamy locker room in the entire book. Nor are there any lesbians. (Sorry, ladies.) Yet it is not who the book excludes so much as who’s included that makes Gay in America, Scott Pasfield’s vivid, rich, and frequently moving coffee table tome, a particularly captivating affair.

After recruiting volunteers from each of the 50 states who were willing to offer themselves and their homes to his gently prying Pentax, Pasfield logged thousands of air and land miles to meet his subjects. Each one would be shot in their environs, not some scythe-draped studio or art-directed set that was propped within an inch of David LaChapelle’s life. As a result, the portraits reveal a surprisingly diverse yet curiously common photographic pastiche of gay male America. The men in this glossily lustrous book are down-home as well as cosmopolitan. As model-handsome as they are mall-ordinary.

They are both privileged and impoverished. The parent and the childless. To the manor born and fresh off the farm. The quick and the dead. Like the flag that flies over them, this tapestry of gay male testosterone is a field of stars, uniformly similar yet snowflake-unique in its genetic stitching—each star framed by the bold, ordered stripes of Pasfield’s vision. Floating free, they would dissipate, lost in the sea of America’s vastness. But when Pasfield’s lens forces us to focus on each, they are glowingly, marvelously, fearfully individual. Visually, the book glows. Yet Gay in America is more than just a collage of pretty portraiture.

These days, every book goes for the standard celebrity Forward. Gay in America’s comes courtesy of award-winning playwright Terrence McNally and husband Tom Kirdahy. Wisely, the book proper is written by the subjects themselves. This first-person narrative simultaneously complements and enhances Pasfield’s goal and vision. Here, the subjects’ own words elevate the occasional, seemingly unremarkable (yet still artfully executed) photograph into something that demands a more informed and, thusly rewarded, second glance. Likewise, this autobiographical voice transcends even the Pulitzer-worthy portraits into soul-wrenching confessions that border on agonizing, with histories so intimate they’re almost too much to bear. A picture may indeed be worth a thousand words, but the words that travel with Pasfield’s photos tend to be well-chosen ones indeed.

The men are presented with deceptive simplicity, identified by first names only, and their city and state of residence. This seemingly rudimentary cataloging of subjects takes on a startling profundity: they are every man. And they are everywhere.

STEVEN FOSTER: Who was the first person you shot for the book?

SCOTT PASFIELD: It was a guy in New York, actually, who ended up not being in the book. He was a really interesting guy, but he just wound up not coming around. It became such a huge leap of faith for people to really share and divulge the honestly important things about themselves that I felt needed to be in the book.

You placed ads to find subjects, correct?

Correct. I went through various profiles on dating sites and contacted people that way. I also created ads on Craigslist, personals, and gay social media networks. I came at it from many different angles. In some places it worked well and in other places it didn’t. Sometimes the ads got snagged in more conservative states. I’m not sure if that was because I wasn’t following some guidelines or if there was some resistance to a “gay agenda.”

So you would search on dating sites? I’m not saying you went trolling on Manhunt . . .

The dating sites were actually a great place to look because that was a really unifying place for men. All men are looking for a date, if they’re not in a relationship. And sometimes if they’re in a relationship they’re still looking for a date. [I was] looking for someone who is out, who is willing to show their face, who might be willing to talk to me. I mean, I didn’t want to look at naked

pictures. It became very obvious who the right people were. Reading their profile told me a little bit of who they were as a person. Once I started doing it, I tried never to repeat a story. I was always looking for something I hadn’t heard before. Someone who did something else for a living, or had a different viewpoint or outlook on life. And in profiles, people tended to show that a lot—if they were really genuine people.

And how many did you cull that down from?

There are 105 different shots in the book, so there’s quite a few from some states. The “gay electoral college,” as I like to say. Every state was represented at least once, but for certain places like California or New York, where there was a large gay scene, [I included more than one shot].

Do you remember one of your more difficult subjects to shoot?

There was a couple who had a son who was dying of brain cancer. That story really affected me before I went there. Emotionally, it was just so difficult to see this amazing kid who was facing death with such a resilient spirit. When I was there he was so pumped up from steroids, and really affected, that he could barely hold his head up. So I had his father and his stepfather lean their heads into his to support him. The shoots that involved death or someone dealing with illness were the ones that were the most impactful for me. I think just four months after the shoot he passed away.

That photograph has an almost Pietà quality to it. The way his eyes are closed, how he’s being cradled. It’s almost angelic in a way.

Yeah, yeah. And he had an angelic spirit for sure. I think that shot nicely reflected such a sweet moment. Thank you.

What session surprised you the most? Or moved you in some way that you hadn’t anticipated?

[Long pause] There’s a guy, Ken from Maryland, who lost his lover in a car accident. A drunk driver hit them. The emotional impact that had on him, and then meeting him in person . . . and how surprising he was in person. . . . He’s such a rugged farmer. He took me around the farm and he was really very shy. It was just not . . . not what I expected. A really great guy who taught me a lot about love through his relationship. I walked away just shaking my head [about] the amazing stories and twists this project had taken.

And it’s strange because when you look at his portrait, and then you start reading the text, you have no idea this story is going to lead where it winds up taking you. There’s a disconnect between so many of the portraits and their essays. Was that a conscious decision on your part? To have that kind of dichotomy between what they wrote and the portraits you took?

It’s interesting you say that, because the stories came to me first. The stories came to me well before the shoot, so I had that knowledge going in. But so many times I just had to make the most out of the environment I was in to make the most compelling photograph. But that doesn’t take into consideration the emotional impact I was trying to get.

A lot of these men were incredibly honest with you. I’d like to turn the metaphorical lens around and ask you what you were feeling after you left them. Can we do that?

Sure. I think a lot of the reason I did the book was not only to educate people and share my world, but also to go on a self-healing journey. It was a personal project I did for personal reasons. And to get this wisdom from these men all around the country, to ask them questions about their lives, to get the wisdom of how to be a gay man in this country, how to be happy—and how to overcome tragedy in many cases—was definitely moving to me. I learned a lot from these guys. And that was a big part of the reason why I did it—growing up with my father the way I did, having a disapproving, born-again dad, and taking care of him at the end of his life and the impact that had on me. I had a lot of healing to do from that.

Some photographers like Herb Ritts and Mark Seliger are famous for their relationships with their subjects. Others tend to keep their distance. Annie Leibovitz once said that the camera was a protection.

How do you approach your subjects?

Well, I usually try to intimidate by befriending everybody. [Both laugh]

What would you like this book to accomplish?

I want to educate people. I want it to be a resource for kids who are troubled, who just want to know that they can be normal, that they can live wherever they want and do whatever they want. They don’t have to follow a prescribed path. I selected a lot of these guys because they never thought they were gonna be in the spotlight. They’re not out there marching in pride parades, they’re just out there living their lives. They don’t define themselves by being gay, but they’re content with being gay. I think that goes under the radar so much that people don’t know that. Hopefully, people will see that there are gay people and they’re in their town and they should love them and respect them and treat them as equals.

I’d like to ask you about some of the other subjects you’ve shot in the past. You’ve shot Colin Farrell, Famke Janssen, Joan Rivers, Lili Taylor, Maggie Gyllenhaal. Beautiful stuff. Your photograph of Dom Deluise with a cigarette in one hand and a martini in the other is hugely famous. Wasn’t that one of the last pictures taken of him before his death?

Yeah. Thank you. I don’t know how famous it is, but it did get a lot of obituary play. [Laughs] I did a lot of work for the Independent Film Channel, and he was a guest on a show called Dinner for Five.

Oh, man, I loved that show. Jon Favreau and just four other actors, or comedians, writers, or musicians, just sitting around telling stories, sharing lessons, having dinner, drinking, and sometimes getting high.

Yeah, what an amazing experience. I did portrait stills of the show, portraits beforehand, and the location shots they used in the opening credits.

Oh my God—I loved that s–t. I knew those photos looked familiar. That’s where the Famke Janssen shot was from.

Yeah, a lot of those you mentioned were from that show. I was, like, their staff photographer for . . . what? . . . 25 of those shows? They did 50 or so. The producers flew me out to L.A. quite a bit—until they went with somebody cheaper. [Laughs] But, yeah, what an amazing opportunity to meet so many legends.

What’s next for you?

More projects like this, hopefully. I’d like to do one on gay men in Europe, or stay in this country and do one on lesbians.

I’m glad you brought that up. Why didn’t you include lesbians in the book?

It would have been very difficult for me. I originally thought about doing both men and women. But it became very clear to me that I couldn’t infiltrate their world without being a woman. I know a lot of gay men. I don’t have a lot of lesbian friends. And that’s a whole other issue that is great for conversation, in terms of the division between the L, the G, the B, the T, and the Q in our own community.

Well, when you and your camera are ready to take on that conversation, we’ll speak with you again.

I look forward to it.

Steven Foster is a regular contributor to OutSmart magazine.

Scott Pasfield Booksigning Events

• Monday, October 24, 3 p.m.

Presentation and signing at Brazos Bookstore, 2421 Bissonnet Street

• Tuesday, October 25, 6 p.m.

Presentation and signing at Rice University, Kyle Morrow Room in Fondren Library, 3rd Floor, 6100 Main Street, 713/348-3893.

__________________________________

Duly Quoted

“Gay pride, to me, isn’t about parades and festivals. It’s about who you are and what you contribute to the community in which you live.” —Paul, Bloomfield, CN

“I have HIV, it doesn’t have me.”—Paul, Phoenix, AZ

“A small part of me is scared that I actually will go to hell.”—Eric, Noblesville, IN

“Love. That’s what it means to be gay in America.”—Dan, Cambridge, MA

FB Comments