Dancing Machine

Hermes Pan set the standard for dance on film

Hermes Pan set the standard for dance on film

by Kit van Cleave

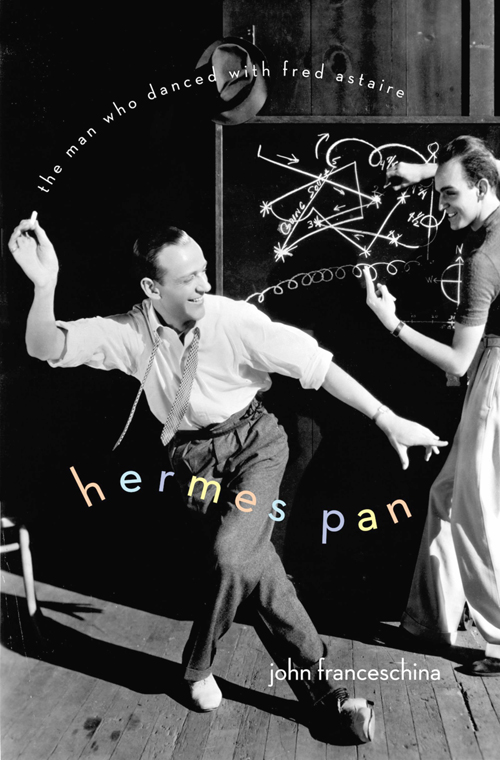

One recent morning I awakened at 3 a.m.; I’d left the TV on, and turned over to see what was on. “Hey,” I said to myself, “that’s Hermes Pan dancing with Rita Hayworth.” I later found out the number was appropriately called “On the Gay White Way” from My Gal Sal (1942). I was so fascinated that I sat up and watched the rest of the movie, because I’d just finished John Franceschina’s new book on Pan, who was Fred Astaire’s longtime choreographer, friend, and dance ensemble inventor.

The son of Pantelis Panagiotopoulous, a Greek immigrant, Hermes Pan came to be known as “the doyen of Hollywood dance directors,” and “the quiet giant of film dance,” Franceschina points out. He also had the longest career of any choreographer (having worked on eighty-nine musical films) and “created a series of icons that permanently etched in the public’s mind for generations what film dancing and, indeed, Broadway dancing were supposed to look like.”

The son of Pantelis Panagiotopoulous, a Greek immigrant, Hermes Pan came to be known as “the doyen of Hollywood dance directors,” and “the quiet giant of film dance,” Franceschina points out. He also had the longest career of any choreographer (having worked on eighty-nine musical films) and “created a series of icons that permanently etched in the public’s mind for generations what film dancing and, indeed, Broadway dancing were supposed to look like.”

Though he started his film work with Astaire and Ginger Rogers at RKO, eventually he began to freelance for 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, and later on in television. He won an Oscar and an Emmy for best choreographer. He was admired for his patient attitude, fluid creativity, and a gift for friendship, becoming lifelong friends with Astaire, Hayworth, Ann Miller, Ginger Rogers, Lana Turner, Richard Burton, Elizabeth Taylor, Tyrone Power, Linda Darnell, and Katharine Hepburn, to name a few of the more famous.

“Armed with only an eighth-grade education, an inexhaustible imagination, and a talent for dancing, Pan rose from the ranks of the Depression’s poor to the most prolific and arguably the most successful of Hollywood’s film choreographers,” writes Franceschina.

Pan loved dancing and putting steps together, which he started doing as a teenager with his sister Vasso. But he was neither a perfectionist, like Astaire, nor overly ambitious, like the 16-year-old Miller, who lied about her age “to get into pictures.” He danced with Hayworth and others because they pleaded with him to do so; he didn’t really want to be on-screen. He thought of dancing as fun, and a way to support his mother and sister—and later on, his other relatives.

Hermes Pan grew up in a rather affluent family, as his father was successful in the hotel and restaurant business in Nashville. In 1922, when Hermes was twelve, his father died suddenly, and he became the family breadwinner. After his mother moved the family to New York, Hermes began to audition as a dancer, and got a few jobs here and there around Broadway.

After the First World War and the economic freefall of the Great Depression (which began with the 1929 stock market crash), Americans with no jobs, little money, and vague hopes had three ways to please themselves: live entertainment (vaudeville, nightclub acts, et al), motion pictures, and each other. After the rise of Vernon and Irene Castle, the premiere dance team of the era, Americans wanted to learn how to dance. Anyone who could create new dances was in great demand, and with the advent of “talking pictures,” song-and-dance musicals were the most popular Hollywood films.

Pan found he could not only create and improvise dance steps but also teach them easily to others—including Ginger Rogers, with whom he made his Broadway debut. Rogers wanted to be a movie star, she told Hermes, and soon she took off for Hollywood. Hermes decided he’d give up cold New York for warm California, knowing that many dancers were needed for Hollywood’s musicals.

And so Pan was hired to assist Astaire, and often replaced his dance partners in rehearsals that would stretch from early morning until midnight. It’s also interesting that Hermes looked quite like Fred: they were about the same height—Pan being a little taller—and dressed alike, often with ties or scarves substituting for belts.

Pan’s homosexuality never became a scandal—people liked him so much, they didn’t want to hurt him, and he was rarely seen with men. In addition, he was a devout Roman Catholic, and in many respects felt “his remarkable abilities were God-given and he was the vessel through which his talent found fruition in the dancers’ movements,” Franceschina notes. So “his place was in the shadow of the performers.”

Despite Pan’s quiet lifestyle, he was once invited to a party by New York’s Catholic cardinal. “Whether or not Pan had been aware of [Cardinal] Spellman’s reputed voracious homosexuality, [Pan was] astounded at what seemed to him to be [Spellman’s] flagrantly public display

. . . it did encourage [Pan] to be even more perspicacious in his private life,” Franceschina reports. Perhaps Pan figured that if being out of the closet was okay for New York’s well-known cardinal, it was okay for him—if practiced discreetly.

Like most gay men in Hollywood in the 1930s and ’40s, Hermes Pan made a point of attending premieres and other social events with the glamorous and beautiful women with whom he worked. He was known for studying what stars did well—and what they didn’t—and choreographed them to look their best, as if the dance were effortless and spontaneous, even though countless hours had been spent in rehearsal.

Why should contemporary Americans take an interest in Hermes Pan, read a book about him or Fred Astaire, and seek out their work through Netflix and YouTube? Because musicals are an American art form, because the work was genius, and because it still thrills today. Get on YouTube and look at how much fun Rogers and Astaire are having in “Pick Yourself Up” from Swing Time, or inventing the carioca dance in Flying Down to Rio. Watch as Astaire and Eleanor Powell tap their way into history in “Begin the Beguine.” Marvel at the silky choreography of “Dancing in the Dark,” from The Band Wagon, when Astaire and Cyd Charisse elegantly fall in love.

Without Hermes Pan’s relentless creativity, would a Bob Fosse or Gower Champion have had such excellent training? Pan choreographed Kiss Me Kate, casting Fosse (who created his own choreography for “From This Moment On”), and worked with the dance team of Marge and Gower Champion in Lovely to Look At and Show Boat. Pan also choreographed Esther Williams’s swimming ensembles and the great Apache dance and “Garden of Eden” number for Shirley MacLaine in Can Can.

For those who love music, dance, and musicals, a list of the best of Astaire and Pan are listed below. Enjoy, as I know you will.

Kit van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Montrose. She has published in local, national, and international media.

Iconic Films of Fred Astaire on Netflix (selected)

Flying Down to Rio (1933)

Top Hat (1935)

Follow The Fleet (1936)

Swing Time (1936)

Easter Parade (1948)

Three Little Words (1950)

Royal Wedding (1951)

The Band Wagon (1953)

Funny Face (1957) available streaming

Silk Stockings (1957)

Iconic Films of Hermes Pan (selected)

Flying Down to Rio (1933)

Roberta (1935)

Top Hat (1935)

Follow the Fleet (1936)

Swing Time (1936)

Shall We Dance (1937)

The Toast of New York (1937)

That Night in Rio (1941)

Weekend in Havana (1941)

Roxie Hart (1942)

Springtime in the Rockies (1942)

Coney Island (1943)

Irish Eyes are Smiling (1944)

State Fair (1945)

The Barkleys of Broadway (1949)

Three Little Words (1950)

Lovely to Look At (1952)

My Fair Lady (1952)

Kiss Me Kate (1953)

The Student Prince (1954)

Hit the Deck (1955)

Jupiter’s Darling (1955)

Pat Joey (1957)

Silk Stockings (1957)

Porgy and Bess (1959)

Can-Can (1960)

Flower Drum Song (1961)

Cleopatra (1963) available streaming

The Pink Panther (1963)