Mary Wilson of the Supremes

by Blase DiStefano

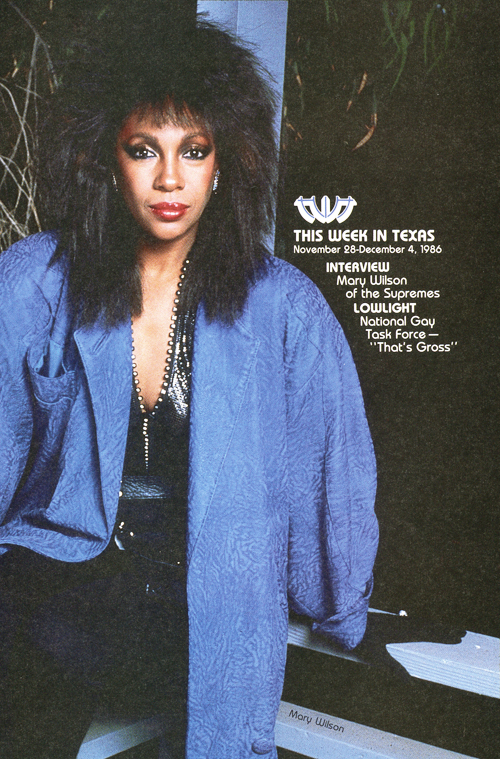

A slightly edited version of this interview ran in This Week in Texas (TWT) magazine on November 28, 1986.

My interview with Mary Wilson was scheduled to take place at 1 p.m. [in 1986] in the lobby of the Adolphus Hotel in Dallas, Texas. Being a Houstonian and not familiar with Dallas, I decided to arrive at the hotel at 11:30 a.m., with the intention of having lunch in the hotel restaurant.

Well, I was ready by 10 a.m., so I arrived at the hotel at 10:30 a.m. Having already read Wilson’s Dreamgirl: My Life as a Supreme, I began skimming the pages to get my mind in gear for the upcoming “event.” Eleven o’clock found my stomach growling, so I quickly proceeded to the restaurant, where I continued leafing through the book while eating.

As I was leaving, I saw two women standing near the hostess, who was about to seat them. It was immediately obvious to me that one of the women was none other than Mary Wilson. I smiled, and as she returned the smile she glanced at the copy of the book that I was holding in my hand.

We said Hi to each other at the same time, then I said, “I’m gonna interview you at about one o’clock.” She replied that she had to get something to eat, that her interviews seemed to be scheduled without much thought given to lunch. Then she added, “I noticed the book.”

Only minutes later, while I was walking through the lobby, the hostess approached me and said that the woman I was talking to wondered if I might want to interview her at lunch. Once I was at the table, Wilson asked me if I wanted to join them, and I asked if I would be able to continue the interview after lunch. I was thinking that I wanted some time alone with her and didn’t particularly want other people listening to our conversation. Wilson turned to her companion and said, “I think he wants to do it later.”

I returned to the lobby and opened the book to any page and began reading. “One day we were eating out when [Diana Ross] suddenly became very angry with me. I have always been a very slow eater, and usually finish last….”

I thought, “Uh-oh.”

The interview began much sooner than expected. After I told Wilson that I was Pisces, too (she was born March 6, 1944) and that when I was much younger, a friend and I pantomimed the Supremes’ songs (to which she replied, without flinching, “Yes, a lot of people did.”), I asked her about ownership of the Supremes name.

Blase DiStefano: I read that you own 50 percent of the Supremes name.

Mary Wilson: Which is actually incorrect. What you read is what I said. But in signing our contracts, I found that years later we had actually signed the name away to Motown, unknowingly to us. So in 1974, when I negotiated my contract, I asked for a percentage of a name that belonged to me. I was granted 50 percent in the event that they sold the name, which was not my deal at all—I thought I was getting 50 percent of the name.

But they’ve not sold the name.

Why would they sell it? So now 12 years later, I’m in litigation over the name again.

Has there been any problem in using the name in the book title?

No. But in my work, if I’m touring (and I had been billing myself as “a Supreme” or “Mary Wilson and the Supremes”), I can’t do that any longer. And that cuts into bookings. Fans will come if I use the name Mary Wilson only. But we’re talking about the public now.

Would you be able to say “Formerly of the Supremes”?

That’s all I can say now in the litigation, but I’m hoping to win the case. It’s been going on for six months now, but I hope it doesn’t last too long because it’s costing a lot of money.

Do you still own some of the original gowns?

Most of them. I own the gowns starting in 1967. All the gowns that Florence [Ballard] wore—I don’t know where they are; I’m still looking for those. I don’t know if Diane has them or Motown has them, but whoever has them, they rightfully belong to me. When Diane and Flo left, everything was turned over to me, which is as it should be—I was the only member.

This may be difficult for you to put in a few words, but for those who haven’t read the book, exactly what happened with Flo?

That’s very difficult. And that’s why I really wrote the book—to explain day-to-day what went on.

Because it was a progression of things.

Yes. It’s very difficult to say this happened and that’s why.

A combination—the rape…

Definitely, it was a combination—the rape and…

Diana Ross…

No, I think it was the rape and Florence not being able to sing lead. I think a lot of people felt that by telling this story, I’m implying that Diane shouldn’t have been the lead singer. That’s not true. I’m saying that Flo and I, as talented people in the group, should have been able to sing too, so that it would have been a shared situation.

Flo had…

One lead. I had more than Flo did.

She had “Ain’t That Good News.”

That’s about it.

You had “Come and Get These Memories.”

And others.

But weren’t most of your other leads after Flo left?

Yes.

Why did they give those leads to you?

Because I bugged them.

And this was pretty much the way it was always, wasn’t it? Always having to bug them to get almost anything?

Well, you mean me as Mary Wilson?

In other words, they were selfish—they wanted everything for themselves; it really wasn’t for you.

It would be unfair to them to say that. Because as the Supremes, we got an awful lot. And for me, I felt I was getting because I was one of the Supremes.

In the beginning, the Supremes were making a lot of money, but Motown was keeping it and not giving any of it to the Supremes.

Right—Supremes. So there’s more to the Supremes than Mary Wilson.

The three of you—I agree. But they weren’t giving the Supremes their fair share.

We as a group were so very young. All the executives were adults. They knew what they were getting, and they went after it to protect themselves as a company. I don’t think that they maliciously tried to grab it all, but in the end they faired much better out of the deal. Had we not been the singers, they wouldn’t have had it.

So it wasn’t to hurt you…

Organizations have to look out for themselves. They were up and coming.

They weren’t big then, so they didn’t know…

They were learning, too. But they knew enough to protect themselves. Being young, we trusted them. We were going to get our fair share…we thought.

What about today? You’re presently receiving royalties from the records being sold now. Do you receive the same now as you did then?

I believe it was in 1979 when I re-signed with Motown as a single artist and released an album, Mary Wilson, which included “Red Hot,” and I think at that time my royalty rate was raised somewhat.

But would that be for previous records also?

Yes, it was. I’m not sure exactly how much, but it still wasn’t top dollar.

It seems to me that Berry Gordy [Motown’s founder] took more than his share of the credit, even for writing songs. Was that only at the beginning?

I think in the earlier days Berry put his name on every song, and that had a lot to do with him being a writer, feeling as a writer that he was not getting his due. So in the early days anything that was recorded, if he could change something on it, that would mean he would have that much more. He was a pretty shrewd businessman, always building up for himself and his company.

I thought it might be insecurity on his part—insecurity about his talent—that he would have to put his name on everything.

Well, I think any time you speak about people, insecurity has a lot to do with what was behind their techniques. But Berry also had a business mind, so he applied it to work for his business ventures.

At this point a waiter interrupted, and Wilson ordered a Perrier. Ditto for me. Without missing a beat, she changed the subject.

I’m writing another book.

Is it a continuation…?

Well, sure. Would I leave you hanging on like that?

I knew there had to be more. How long before it’s released?

I’ve started already. We’ve gotten an outline, etc. It’s going to start with 1970 and continue through today.

How long did Dreamgirl take?

About three years, but that was different, mainly because it was further in the past.

How did Dreamgirl come about?

I decided a long time ago that I wanted to write a book. And that was because of a teacher I had in high school who thought I had the ability to transform a story into something that people would be interested in reading. He said that I had a wonderful way of making people come alive, that I had the ability to show compassion in people. It must have penetrated, because I started keeping a diary, writing down everyday things that were going on in my life—teenage things, like “Oh, Johnny sure is cute” or “I looked at Johnny today and he didn’t look at me.”

I wrote some of the same things.

[Laughs] Right. But I continued writing in my diary throughout my career. I remember in 1965 when we were doing an interview in England, the journalist asked what my future plans were. I said, “One day I’m gonna write a book.” And he said, “Oh really, what is it gonna be about?” Diane and Flo are sitting there, right? And I answered, “About us.” Diane looked at me rather strangely, and Florence looked a bit perturbed. After we became famous, I knew I had something to write about.

I think it’s a good thing you did write about it, because there have been an unbelievable amount of rumors.

Do you think it helped squelch any of the rumors?

Definitely.

Yes? ’Cause I tried. You know, no one really knows us. They speculate on what Diane is really like. They love to hate her; they don’t know why they love to hate her. And then with Florence, there was such a mystery surrounding her. With me, it was like people loved me, but I got the feeling that they felt that Diane was a success and I was a failure, and Florence was more of a failure ’cause she died poverty-stricken. I wanted to write about us as people. I thought that people didn’t know us as people.

It’s still hard for me not to think of the Supremes as a group. Even when it was changed to Diana Ross and the Supremes, to me it was still the Supremes.

I know, and do you know I’m getting letters asking me why I should write the story of Diana Ross? To that I say, “I’m not writing the story of Diana Ross, I’m writing the story of the Supremes. Don’t forbid me from writing my own story when everybody else out there is writing books about us.”

There was going to be a book coming out soon that would tell some of the things I had to say written by an outsider who was looking in. They didn’t know; they would have told things that Diane did that would make you start to hate her. A lot of the people hate me for saying the things I’ve said, and they want me to feel bitter about it, but I don’t. I love Diane. I’m just telling them what she did. If I can love her the way she was, they should be able to also.

People are having a hard time accepting the truth.

Well, it’s not my fault; I didn’t make it up. Would they have preferred someone who hated Diane to have written this? It would have been written completely different. And they really would have hated her.

After reading it, I didn’t come away hating Diana Ross.

You just realize that’s the way she was. Now that was also her strong point—that’s why she became popular. She was not like me—she did not wait for things to happen; she went out there and made things happen. I admired that in her.

Personally, I think she went to an extreme.

True, but she is an extremist. You know what I mean? Sometimes people have got to do things and go all the way to let some of us know that it can be done. If she hadn’t done the things she’s done, she wouldn’t be Diana Ross. We would not have one black diva up there other than Diahann Carroll.

Is Diahann Carroll like Diana Ross?

No. I think she’s more of a businesswoman. I think she’s taken her time to do a lot of things. Like me—I’m just starting—you haven’t seen the last of me. Someone asked me, “How does it feel to know that Diane is more successful?” I said, “Wait just a minute. Who says she’s more successful? I think I’m extremely successful.”

I guess it depends on one’s definition of “successful.”

Right. I think she is very successful, and I admire that…in one area. I’m very successful as a human being. I’ve worked on myself, to be more confident with myself, to be more at ease. I’ve worked so that I can sleep at night, so that I can face each morning thinking, “Wow, what new experience is gonna happen, what new person am I going to meet?” I think I’m very successful. In fact, in terms of coming from a no-name or faceless person in the Supremes, I’ve become Mary Wilson again.

It’s obvious that a nice change is taking place.

Oh, good.

It’s really nice to see a 42-year-old woman sitting across from me who is still learning about herself, who loves herself, and who is also willing to sit here and be accessible like this.

Thank you. You know, someone said, “You told about all those guys you had and about some of the things you did.” I think we harbor in us certain things, and we’re afraid that if anyone finds out, they’re gonna hate us. If I make some mistakes, I want people to know about ’em. I want them out of the way, so I can go on with the rest of my life.

You’ll find that people will appreciate your honesty.

I hope so, because a lot of people look up to entertainers, and they often don’t realize that some of these people are just as insecure as they are. Even though I was always insecure, what saved me was that I was always searching to be happy. And in writing this book, I said I was going to ’fess up to everything, hoping that this would help other people ’fess up and go on with their lives too. If you’re an underdog or second banana, feel good about being it. I always thought I was a star even in the background; not for one minute did I feel bad about it. ’Cause I knew I was giving as much energy and as much love in my “oooos” as Diane was giving with her words. And I was giving ’em for real. See, everybody can’t be Diana Ross. I don’t want to be Diana Ross. I like Mary Wilson. And I know there are a lot of Mary Wilsons out there. And Mark Wilsons, too. You gotta feel good about yourself.

That’s important to show people.

That was my point.

And it’s coming across.

But you being a Pisces, too—it’s easy for you to understand.

Do you know much about astrology, or do you just dabble a little bit?

In the seventies, I was into astrology, numerology, astral projection…just about everything. In my second book, I’ll talk about a lot of that.

Metaphysics is most interesting to me right now.

Well, I read The Science of Mind, which is wonderful, ’cause it’s a look into yourself. It’s like uncovering all the negativity and finding the positive, which is God inside or the God-spirit, or whatever term you prefer. It’s good to know that it’s not way out there someplace. It can be right inside here. If you can look beyond what people perceive to be and really see what they are, you can love them regardless.

This is what I was trying to say about Diane in the book. I love her regardless of what I said, and it’s because I love her that I said it. If I didn’t love her, I would have written it another way.

You could have been a real bitch.

I know it. What would Joan Rivers have said? When I did The Joan Rivers Show [Tuesday, November 4, 1986], I was so afraid she was gonna say, “Now, come on, Mary, tell me, was Diana really a bitch?”

Well, basically, she did.

Yes, but she was nice about it. And you know what? I enjoyed her, because she didn’t throw jokes all the time. There was a real human behind that.

But I was disappointed that you didn’t sing.

I got a call yesterday [November 6, 1986], and they said their ratings were the highest they’ve had! So they definitely want me to come back and sing.

I’m already looking forward to it. Let me see if I can get a few more questions in.

I can go on and on…

You’ve experienced prejudice, but not as awful as it could have been. How is it today?

For me, being in the Supremes, we didn’t live the type of lives that other black people lived. So we didn’t experience prejudice on a day-to-day basis. However, my family are just normal black folk.

Since people don’t know who your family is, do they still experience prejudice?

Sure. Prejudice is still there for black people, but it’s not the same. As the generations go on, it’s not so ingrained. For my parents and people of that generation, it was very difficult, because they lived being treated badly. I mean really badly—not being able to drink from the same water fountain and saying “yes, ma’am” and “yes, sir” to younger people.

Today, I think Blacks encounter prejudice just like any other minority. But Blacks, Jews, and other ethnic groups are being accepted now, mainly because of money and power. They are rising above certain monetary positions, and the more of us who do that, the more we will be accepted.

We’re obviously not going to have time for all the questions I had planned, but I want to get this in. In the book, you wrote about a lesbian yelling “I love you” to Martha Reeves. Could you tell me what your feelings are about gay people?

I think they’re people. Who am I to say? I have not been an angel all my life. I’ve done a lot of things I wouldn’t want the fans to know what I’ve done.

Is there just one that you might…

No, I’m not gonna tell. I will never tell.

Tom Jones is enough, right? [Mary Wilson had an affair with singer Tom Jones while he was married.]

Yes, that’s enough. That one I’ve almost lived down. But I thought if I put it out there, I’d get over it sooner.

I have friends who are stars, who are gay, who are men, who are women. I’m the kind of person who takes people as they are; I hope they will take me as I am. In terms of gay, what can I say? I have no opinion. I really have no opinion. And I don’t want to be forced to give an opinion on it.

Do you have any friends who have AIDS?

I’ve had many friends who have died of AIDS. A young man in L.A. who was a big Supremes fan was in the record end of the business, and I think he wanted to do some things with me. There were rumors he had AIDS, but then it was no, he didn’t have AIDS. I remember thinking of him and wanting to get in touch with him when someone called me and told me that he had just died. I was really upset. Other people I’ve known have died, so that’s why I do benefits for AIDS whenever I can, just like I do for sickle cell anemia.

It’s very sad. One guy came up to a book-signing and said, “I’ve just been diagnosed as having AIDS, but I want you to know I love you, and you’ve brought many things to me.” My heart went out to him.

I don’t want to end the interview like this, so can I ask one more question?

Sure.

We’ve touched on this, but in the book, you said, “I try to cover up my deficiency by developing a pleasing personality. I’m still a young and frightened girl.”

That was written in 1962 for a theme paper.

How has that changed?

Now I’m more mature and not so frightened, but I still recognize that I am that little girl. But the little girl doesn’t have to be frightened of the big world; the little girl doesn’t have to feel so insecure because I’m not an intellectual, or I’m not a Leo or Aries, or I’m not the president of a company. But I’m just me, and me is okay.

You can accept that little girl in you.

Right. At the age of 17, I was starting to wonder. Now at 42, I’ve sort of figured out the puzzle of Mary Wilson. And I can get on with my life.