The Impatient Bostonian

Immense wealth helped Eleo Sears live a progressive early-20th-century life

by Kit van Cleave

Eleonora Randolph Sears was one of the 20th century’s most admirable people, but few have ever heard of her. Eleo, as she was called from childhood, was handsome, headstrong, individualistic, and rich enough to generally do as she pleased.

She was also brave, generous, athletic, and ethical. She loved animals and felt a kindred spirit with horses. She could also be steely in dealing with those who betrayed or disappointed her, or did not have the same energy and commitment she gave to every endeavor. In Prides Crossing, biographer Peggy Miller Franck outlines Sears’s public and secret lives.

Born in 1881, when fortunes were really fortunes, Eleo found herself in a family with elite credentials and enormous wealth. Her neighbors were the “Boston Brahmins,” or First Families, led by the Cabots, and including the Lawrences, Masons, Warrens, Amorys, Curtises, and Lorings. “By the mid-1700s, Eleo’s great-great-grandfather, David Sears, was said to be the richest man in New England,” writes Franck. By Eleo’s birth, that fortune had been so carefully looked after that she would be set up for life, even though she would have enormous expenses.

These First Families were quite generous to their beloved Boston, donating funds for schools, universities, hospitals, and designated charities. It was expected that if they wanted to receive special treatment (and they did), they would wish to be seen as benefactors to the city. They could also close ranks to protect a wayward or eccentric member of their group, and suppress scandals.

These First Families were quite generous to their beloved Boston, donating funds for schools, universities, hospitals, and designated charities. It was expected that if they wanted to receive special treatment (and they did), they would wish to be seen as benefactors to the city. They could also close ranks to protect a wayward or eccentric member of their group, and suppress scandals.

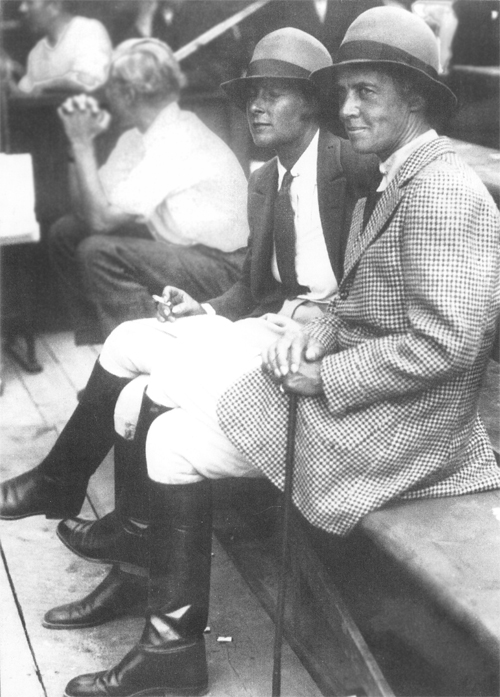

Growing up in this hothouse environment, Eleo became an “expert horsewoman, national tennis champion, and formidable competitor in almost every other sport on land and sea,” Franck notes. She raced cars and boats, learned to fly, and even created competitions such as “pedestrianism,” which involved walking as many as 35 miles at one stretch. As a leader in the “horsey set,” Eleo stopped riding sidesaddle early on and took to riding astride so she could challenge the local polo teams to let her play. This necessitated her taking to wearing trousers (and later, jodhpurs or leather leggings and riding boots).

On the other hand, when venturing out socially the young Eleo was always elegantly dressed, wearing the best in jewelry and furs. She was beautiful enough to have all the young men buzzing around; her favorite escort was Mike Vanderbilt. But soon it was apparent that she would not marry him—or anyone else. Still, she was smart enough to realize that she could only push her individualism so far.

“Eleo was keenly aware of the fate that befell those whose private lives moved into the public domain,” Franck reports. “Boston’s First Families had always entertained themselves by tossing off startlingly frank observations about secret failings within their circle, while they served tea and pastries. . . . To become a source of sordid speculation and twittering innuendo would have violated Eleo’s sense of her own dignity. [She] also had no desire to put at risk her comradeship with her many male friends.”

But she was finding a real need to assert her desire for love and companionship. In 1917, she met l8-year-old actress Eva Le Gallienne while in New York to attend the theater. and a close relationship was formed. Then in 1922, while in Paris, she met Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas, and also began a long friendship with David Windsor, Prince of Wales and the future King of England. Her social connections, exquisite manners, and wealth—as well as her looks—made her a magnet for the Sapphic and bi-ladies set. Among her friends and lovers were Isabell Pell, Mercedes de Acosta, Isadora Duncan, Alla Nazimova, Tallulah Bankhead, Greta Garbo, and Marlene Dietrich. Eleanor Roosevelt was one of Eleo’s close friends and often stayed with her at her various residences.

While Eleo always rode horses, she took up tennis in the 1920s with her usual ferocity, becoming one of the top players of the day. During World War I and the crash of the stock market in 1929, “most Boston risk-averse First Families were able to maintain an approximation of their pre-cash lifestyles in homes paid off by earlier generations,” Franck points out. “The stodgy investments that made up her nest egg, which had looked so yesteryear in the gogo 1920s, saved her from the quicksand of the stock market in the 1930s.”

Franck describes Eleo’s fascinating life through decades of political and social upheavals. In her 50s, the millionaire horsewoman took up breeding and racing, with huge expenditures in staff and stock that would have staggered many Americans.

Unfortunately, as Eleo aged, she was taken up by Marie Gendron, often called “Madame,” a Frenchwoman who knew a good deal when she saw one. She seduced the older woman and then started isolating her from old friends and relatives. Soon Madame and Eleo were living the high life in Palm Beach, with only each other’s company. Madame was often seen in Eleo’s furs and jewelry, and wore designer suits and dresses. By 1965 she had Eleo’s power of attorney, and was running the household and stables.

Eleo would not have wanted to live without her constant good health; on March 26, 1968, she passed away peacefully at the age of 86. Her will had donated to six hospitals, all of which she had helped in the past; the rest of her estate was to go to Madame, who tried to cut the hospitals out of the gifts. Madame lost in court and was left with only about $40 million with which to make her way in life.

All in all, an excellent book about a previously unknown American leader.

Kit van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Montrose. She has published in local, national, and international media.

FB Comments