Directed By

An award-winning anthology features interviews with queer filmmakers. Includes interview with Dan Roos SPECIAL WEB VERSION.

Excerpt by Matthew Hays

Additional material by Tim Brookover, Donalevan Maines, Angel Curtis, and Neil Ellis Orts

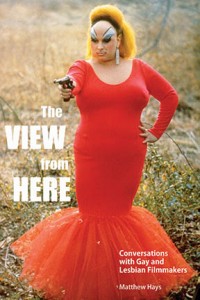

In May, the New York-based Lambda Literary Foundation presented its 20th annual awards for fiction, nonfiction, and poetry written by gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender authors. The winners included The View from Here: Conversations with Gay and Lesbian Filmmakers, from Arsenal Pulp Press, a Canadian publisher known for its queer and alternative titles. (Another Arsenal title, First Person Queer, edited by Richard Labonte and Lawrence Schimel, was honored with the Lambda award for top GLBT anthology.)

In View, the film pros interviewed by the author, Montreal critic Matthew Hays, include familiar names (John Waters, Pedro Almodovar, Bill Condon, Gregg Araki, Gus van Sant, and John Cameron Mitchell) as well as cult and porn figures (Kenneth Anger, Bruce LaBruce, Wakefield Poole).

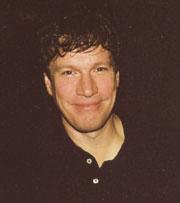

One name that is not as recognized is Don Roos, though his movies are popular with queer audiences. These have included Single White Female, Boys On the Side, the guilty pleasure Diabolique, The Opposite of Sex, and Happy Endings. Roos began his career by writing for two of the television series fondly recalled for their camp quotient: Hart To Hart and The Colbys.

Roos is next set to direct Love and Other Impossible Pursuits, based on the Ayelet Waldman novel (with a screenplay co-written by the novelist and the director). With Jeffrey Dean Morgan, Jennifer Lopez, and Lisa Kudrow set to star, Love is scheduled for a 2009 release. Roos is surprisingly candid and melancholy in his interview in The View from Here.

Roos is next set to direct Love and Other Impossible Pursuits, based on the Ayelet Waldman novel (with a screenplay co-written by the novelist and the director). With Jeffrey Dean Morgan, Jennifer Lopez, and Lisa Kudrow set to star, Love is scheduled for a 2009 release. Roos is surprisingly candid and melancholy in his interview in The View from Here.

Don Roos: The Opposite of the Norm

(interviewed by Matthew Hays, excerpt from The View from Here)

UNABRIDGED—SPECIAL FOR OUTSMART WEB READERS

Like so many gay filmmakers, Don Roos has a knack for conjuring up powerful women. Many will recall the girl-on-girl rivalry in Single White Female (1992), the suspense film that Roos wrote in which Bridget Fonda takes in roommate Jennifer Jason Leigh, only to discover that Leigh is insane and obsessed with taking on Fonda’s identity. He also wrote the critically-savaged remake of Diabolique (1996), in which Sharon Stone plays a (surprise!) scheming murderess. And in The Opposite of Sex (1998), which he directed and wrote, an embittered Christina Ricci manipulates those around her, including her gay half-brother and his boyfriend whom she seduces.

Roos began his film career as a writer, taking a screenwriting course at the University of Notre Dame when he was in his early twenties. In the 1980s, he contributed to a number of popular television shows, in particular Hart to Hart and the Dynasty spin-off The Colbys. Roos also earned a reputation as a script doctor, working to improve screenplays others had already written. (Roos says he is too much of a gentleman to name the films he’s been brought in to doctor.)

A turning point for him came in 1998 with the release of his directorial debut, The Opposite of Sex, the ensemble comedy that made many critical top-ten lists that year. After this success, Roos expected that getting studio support for films featuring gay characters—or even heterosexual characters who happened to be complex—might get easier. But not so, according to Roos, who says that studio executives interfered with his follow-up film, Bounce (2000), starring Ben Affleck and Gwyneth Paltrow, which resulted in its box office failure. This made his next feature film, Happy Endings (2005), all the more difficult.

His experience thus far has been somewhat disappointing to Roos, not only because of how studios treated him, but also by the critical and public reaction to the kind of narrative complexity and character ambiguities common in his films. He now lives in Los Angeles with his partner, actor-writer Dan Bucatinsky, and their adopted daughter. A conversation with Roos is much like one of his films: insightful, intelligent, sometimes digressive, and always sharp and witty. Sadly, even in the post- Brokeback Mountain Hollywood, Roos still sees problems getting gay characters portrayed honestly on the big screen.

Mathew Hays: In interviews, you’ve talked about the fact that when you were growing up, homosexuality was a huge taboo. Some of the filmmakers and writers that I’ve spoken to said they began writing precisely because they were gay. Was that your experience? Did part of the act of writing have to do with wanting to talk about something?

Don Roos: No, it didn’t for me. I think I became a writer because I felt very different and strange, and writing gives you a sense of control. When you’re writing, you’re not playing ball, you’re not with people; you’re very much alone. I think writing is a good refuge for misfits of all shapes and sizes. Being an outsider or a minority or an oppressed person in the kind of society that I grew up in—which included my own home—I think I wrote just to get some kind of power, just to make a little world for myself where I could punish people or make them do things. Of course, it’s connected to being gay, but I didn’t start writing to talk about gay issues, at least not consciously.

Was your home life tough?

I grew up in a Catholic family in the 1950s, which was a very rough environment for a child to grow up in. Morality permeated everything, as did group thinking, discipline, and lessons about appropriate and inappropriate feelings—you know, your typical repressed ’50s household.

You’ve talked about the importance of gay images on the screen and what that can do for people. Do you remember the first gay character you saw on film or television?

No, but I remember Peter O’Toole with his shirt off in Lord Jim [1965]. The first gay image … that’s really hard. I don’t know what that would be aside from the camp images or the mysterious images that have a lot of power over gay men, like from The Wizard of Oz [1939] or Peter Pan [1960]. Mary Martin playing Peter Pan is a very strange image for a kid to hang on to, but I was obsessed with the yearly broadcast of Peter Pan on television. I couldn’t have been more than four or five. But an openly gay image … my God, was there one? There were a few people who appeared on talk shows, like Truman Capote, and Paul Lynde, who made me uncomfortable.

Why?

Because I sensed that he was something different or maybe like me. There was a lot of disapproval of how he was—my mother would laugh at him, my father would frown.

Both of those examples are people I grew up with too. They were both entertaining figures who were also train wrecks, in a way. Both Capote and Lynde died alcoholics.

There’s a lot connected to those kinds of images. They suggest not only a sinful lifestyle, but an unhealthy one too. It’s a strange feeling that leads people to sense their own damnation and extinction. That was what was so awful about AIDS. It seemed to some of us like, “This is the nightmare of our childhood come true,” that being gay leads to death.

You began your career as a screenwriter. Can you tell me about your first writing gig?

My very first one was for Hart to Hart [1979-84], a television show in the early 1980s [starring Robert Wagner and Stefanie Powers] with quite a camp sensibility. I wrote four spec scripts, meaning scripts that aren’t commissioned. I got to meet the producer who happened to be Mark Crowley, who wrote The Boys in the Band, the very important early gay play. He took an interest in me and gave me some assignments, so I suppose the gay mafia helped me in the very beginning. I wrote for television throughout the ’80s, mostly for undistinguished shows, because I was very shy and didn’t feel confident pitching to better shows. I also thought I wasn’t capable of writing for cop shows or medical shows, that I was more soap opera. So maybe that was my own internal homophobia at work, or maybe it was my natural shyness or insecurity. I don’t know. Finally, I wrote a script on my own, a feature-length film called Love Field [1992], and managed to get it to two producers who liked it, and then Michelle Pfieffer got on board [who was nominated for an Oscar for the role in 1992]. After that I forgot about television for a long time.

You talk about internalized homophobia, but personally I’d rather be writing for Dynasty than a cop show.

I wrote for The Colbys [1985-87], which was a Dynasty spin-off, and a series called Paper Dolls [1984] that was a drama about two young models. I wrote for shows that dealt with human emotion and interaction—the things that people said or did to each other rather than gunshots or legal cases or medical problems. I was really attracted to soap opera. A lot of people call my movies soap operas.

Soap operas have such a bad reputation, but shows like The Sopranos or Six Feet Under are essentially soap operas.

Absolutely. When I started doing film, the powers that be didn’t care what I’d done in television. I thought making films was going to make it easier for me to write about things that I cared about. The television censors were crazy and the networks were timid. Television, I think, is a terrible, terrible place to work even today because of stupid people telling you what you can and can’t say to America. I just think that the people working in television aren’t very intelligent.

Like a salivating gay dog, I recently purchased the first, pre-Joan Collins season of Dynasty on DVD. There is some really interesting stuff in that show, including the gay son who’s an outcast and getting drunk all the time. I’m sure the writers went through a terrible meat-grinding process to get that character on the show. It’s a really interesting cultural artifact, a reflection of America in the ’80s.

I agree. I think television shows can’t help but be a reflection of the age in which they are made because they have to be popular to succeed so they have to somehow speak to the masses, even if it’s unconsciously to the desires of the public at the time. Television can’t help but be a great way to look at a culture, and what the values of that culture are. For someone who is in opposition to the culture, though, again, television is not the greatest place to work. Although I watch an awful lot of television and I love shows like The Sopranos, Six Feet Under, Sex and the City, and 24. There’s a lot of great British television too. But in general, American television is pretty much unwatchable. Characters are never deeply unlikable or deeply complicated.

Going back to your writing, you speak of camouflaging gay characters in some of your screenplays.

I did that a lot in the beginning. But I may have to go back to it, just because sometimes putting gay characters out there hurts you. The studio will say, “Oh, there are gay characters, it’s a gay film, we have to market it a certain way,” which is very frustrating. I don’t know how Brokeback Mountain got made. It will probably do us more harm than good because it will be pointed to as an example of the fact that Hollywood is open and that things are changing, but believe me, on the frontlines they aren’t changing, they are getting worse. It’s harder to put gay characters in a film now than it was ten years ago when I did The Opposite of Sex [1998]. Camouflaging gay characters can take many forms. A popular way is making the lead character’s best friend sassy, but female. Or the lead can be an outcast who is not a happily accepted member of traditional heterosexual Christian society. A black character can also masquerade as a gay character, as well as any character who is out of step with the mainstream.

Of course there is the popular theory that many of Tennessee Williams’ characters, particularly his strong women characters likeBlanche DuBois, were in fact gay characters.

I don’t know if they were for a fact, but they probably were. I think Williams probably drew out their internal spiritual life and soul from his experiences as a gay man. Of course, if they were actual gay characters, their experiences would be quite different, and they would be perceived quite differently. But camouflaging is a way for the gay writer to get inside his characters and to tap into a little of the anger and anxiety that you feel as a minority person.

The fact that you wrote Single White Female [1992] makes sense to me, seeing as a character is murdered by getting a high heel in the head.

That was all kind of unconscious. I thought, “Oh, that will be fun.” I was thinking, “What is the most dangerous thing about a woman?” She wasn’t going to hit him over the head with her vagina, so I thought, “Well, she’ll hit him over the head with her high heel shoe.”

Were you conscious of other issues—I mean, it’s about these two powerful women.

Well, I was conscious that none of the straight white men in the film were good guys. The only man who survives is the gay neighbor upstairs. The characters who had power, compassion, or intellectual ability were either gay or female. That [characterization] was very consciously done. I was tired of those movies where the girl is just a victim to be offered up to the evil person, where women are stupid and weak and teetering in high heels.

In The Opposite of Sex, you bring a lot of these sexual issues to the fore. I’ve always felt that Christina Ricci’s character was your voice, was the voice of a gay man at the center of the film.

Yeah, I think you’re right. I can talk about her being a real character in her own right. If you look at it, she is a woman defined by her sexuality. [In the film], Christina’s character doesn’t really have any sexual appetite, but she is defined by society as what she is because of her sexual attributes, because of her breasts and because of her attitude, independence, and unwillingness to obey convention. She’s defined by society because of her sex or her interest in sex—or what they presume to be her interest in sex—and, of course, that is very gay. Gay men are defined [in that way] by people all the time. They think that the most important thing about a gay man is that he wants to sleep with another man. So in that way, Christina’s character is a gay man. She’s also very thoughtful and confused about sex. She’s unconscious about it in the beginning and over the course of the film it begins to trouble her, which is very much like my experience of being a gay man: what’s this thing that separates me from everyone else? Where is it located? What does it mean about me that I want to be with a man instead of a woman? Why does that define me, because my taste for chocolate or vanilla does not define me nor does my taste in sports? What is it about my desire for the same sex that totally separates me? What is everybody’s desire? Christina’s character is a rebel, she’s impatient with a morality she doesn’t really understand, and in that way she’s a very brave character; unlike myself through most of my life. She also does what she wants to do and doesn’t spend too much time in any kind of moral argument, but I don’t think that’s very gay. I think gay people spend a lot of time agonizing over the things they do.

I think that’s why she’s so refreshing. That’s wish fulfillment, because so many gay people would like to say, “Fuck off.”

She’s very powerful that way. That’s what I liked about her. In fact, that’s why we wrote the character. I wrote all the voiceovers for her narration before the movie began. We shot the film without her voiceovers, though, and I directed everything as straight scenes. I’ve discovered that characters behaving honestly can be funny. We shot everything without pushing for laughs, so it didn’t seem to us to be a comedy at the time. I knew it was, but we were more concerned with the internal lives of the characters. When I finally edited her voiceover narration into the picture, it was really, really shocking because I had come to treat these characters very intently and lovingly, but there she was in her voiceover making fun of them, being very bold and not being particularly discriminating in her hostility and not really taking an empathetic view of anybody. I thought, “Oh my God, I hate her! She doesn’t know anything, she’s a kid, she’s a punk. This is complicated.” I grew to love it, but it was a shock in the beginning. I do think she says some horrible things and her language is terrible. She’s pretty awful. But I appreciated her spirit more and more.

I was really struck by the film when I first saw it. We talk about how far we’ve come, but there’s still something radical about a film where gay and straight characters are given equal time and equal respect.

It’s hard to pull it off. There was this time during the 1990s when movie people weren’t paying a lot of attention and you could get an independent film made quite easily. And let’s face it: Christina Ricci is a very cinematic person. She’s very beautiful and compelling. I think people thought it was going to be a “funny” comedy, but once we got the audience in there, we started dealing with difficult things like sex and death and being gay. In that way, it was kind of a stealth bomb. It’s very hard to surprise audiences now.

I think audiences are more alert to signs of gay culture, signs of what they don’t want. I think every year the audience gets stupider and stupider and that they’ve been trained to get that way. I mean, what can you say about a country that re-elected Bush? How much can you admire their intelligence? Seriously, it’s not fun.

I was in shock on election night.

It’s a deeply stupid country. I think when we grow up we think everybody is like our family or like our neighborhood block and that they’re all smart and they all care. Well, they’re not. They’re very difficult, and a lot of them are dumb. And the ones who are smart are distracted by what’s fashionable and in vogue. I think it’s difficult for thoughtful films to get a good reaction from movie audiences in America because they want to be soothed by movies; they don’t really want to go to the movies to think. You get a highly praised film like Pride & Prejudice where not a single real disturbing thought or feeling occurs in the entire film. That’s America’s idea of a thinking-man’s film today. Maybe I sound bitter, but as you grow older you lose a little of that sense of, “It just takes a good film and they will come.” I don’t think that’s true. There are some barriers in the business that work against that. The principal one is really the culture as a whole. Where is this culture going? A culture that is based on fear, one that is controlled by its fears, and is not going to be open to anything challenging in their entertainment? As for films with gay characters or content, studio types will say, “Well, it’s not that I don’t want to see that,” and ask, “Do they have to be gay?” After I made Happy Endings [2005], which took two and a half years to make and fell apart several times, my own producer told me, “In the next movie, don’t put a gay person in it. It’s so much harder.” So, even your own team will dissuade you, just because it is so impossible.

I don’t know how Ang Lee got Brokeback Mountain [2005] green-lit, but he is an award-winning director who can do what he wants. The problem with Brokeback Mountain is it will take up the space that a lot of smaller independent films could’ve taken up. There are people in the business who will point to it and say, “We’re not bigoted, we made Brokeback Mountain.” So it’ll work against us for the next ten years. I think a lot of gay filmmakers are consumed with jealousy that he was able to do it. “Why could he do it and I can’t?” And they are also aware that it will be used against us for years and years.

I think another part of the reason Ang Lee was able to make Brokeback Mountain was because he’s straight.

He’s the gayest straight man I ever met. The Wedding Banquet, Sense and Sensibility, and Brokeback … and I think he’s a very open guy in terms of what appeals to him. I wish he was gay. I would love to claim Ang Lee for our team, but he’s not. That is one of the reasons it’s safe. In order to put a gay thing over in this country, it helps if it’s shepherded through by a straight person. In fact, one of the ideas I had for The Opposite of Sex was, “I have to make this lead character a buxom, beautiful, blonde straight girl who hates gays, or has the normal contempt for gays that most Americans have, and she will shepherd the gay themes and characters through this film and people will trust her.”

It was interesting to see how Brokeback Mountain played in more conservative parts of North America. It was shot in Alberta, Canada’s most conservative province.

I don’t think you’re going to fool a straight audience by putting the gay leads in cowboy shirts and putting a buffalo on the poster so that they’ll think, “It’s just two cowboys chewing the fat sitting on the fence talking about their cattle.” You know, for a gay man, as you grow older, you come to understand just how threatening homosexuality is to others. When you’re a child, it seems that people are very, very stupid and limited. But the depth of the hatred and the fear is something you realize when you grow older. The basic biological fear that many people have is very daunting.

It’s not only a difficult time to be gay in America, but simply to stay sane, given what’s happened in Iraq and Washington.

The Christian part of America is getting increasingly harder to deal with because it is so intrusive and aggressive. The Republicans’ use of homophobia to galvanize voters like they did in the 2004 election was very discouraging. On the flip side, I’ve never been able to live my life more freely than I have in the last ten years. I’m a citizen of California, which has my loyalty, not the United States—I’m not what you would call a patriotic American, but I am a patriotic

Californian. I’m not discriminated against in my business for being gay. They don’t care if I’m a gay writer or a gay director at all, they really don’t. They don’t discriminate against me socially or in terms of awarding me jobs. They couldn’t give a shit about my sexual preference. My partner and I have a home together, our doctors and lawyers are quite accepting of us, as are our neighbors and the people who work for us. It’s not a problem. We also have a daughter. I have a very free and full life as a gay man in California. It’s a weird feeling to be that free and open in your daily life. When I was fifteen years old, if I could have thought that one day I could have all these things as a gay man and be out as a gay man, I would not have believed it. On the other hand, we live in a society that is so vocal about its dislike for who I am and how I love, it’s tough.

After the success of The Opposite of Sex, I understand you were inundated with gay screenplays.

Yes, but I don’t direct other people’s work, so it was all for naught.

Then you chose, as you say, to write straight.

I wrote Bounce [2000] immediately before I made The Opposite of Sex to prove that I could do straight. I had never done a movie where I had a straight man for a lead. The Opposite of Sex was very, very gay, and I wanted to write in the mainstream and I wanted to write a movie without irony. The Opposite of Sex was so easy to write because it was ironic, which is a natural tone for me, and I wanted to see if I could hide and do a straight tale in every sense of the word, about straight people told straightly—a straight love story. The script wrote itself quickly, but it was a very difficult movie for me to make.

Originally, I wasn’t going to direct it, but we couldn’t find the right director. Then The Opposite of Sex came out and because it was successful, the studio said, “Well, would you like to direct this?” I thought, “Yes, I can make it edgier.” But the studio wouldn’t let me make it as edgy as I wanted and in the end the test audience wanted it to be even less edgy. The two stars, Gwyneth Paltrow and Ben Affleck, were wonderful—I just love them both. It was a thrill to work with them. When the film was finished, the studio took it to New Jersey to test screen it. Miramax was very responsive to the test audiences, who didn’t like the dark parts of Ben’s character. They loved Gwyneth’s character because she’s a victim throughout the entire movie, like a lucky victim, that’s the role. But the complicated guy who lies and who’s divided and who’s dark and responds very humanly and who has weaknesses and strengths—they didn’t like that. They wanted him to be one thing or the other. Can he be either a bad guy or a good guy? That was very hard for me to see. The net result was that the film made no more money than it would have if it had retained the integrity of the first cut—in the quest to make characters less objectionable, you lose as many people as you gain.

You weren’t very happy with the process of making that film.

I’ll never do a studio movie again. Never, never, never. That’s how much I liked it. I would also never work on a commercial television network show again, ever. I’m not the kind of person who’s like, “It was a horrible experience, but I’ll go in there again and make it work.” I know these people are never going to change. I’ll kill myself on the wheel trying to get it to work. It’s not for me. Your voice is not respected. They don’t really want to hear from you. So why do it?

I really liked Bounce and put it on my top ten list that year. I was very drawn to what I saw as your sensibility because it felt like an ode to Douglas Sirk. I liked seeing Ben Affleck cry and I recognized the dark elements. And I could feel you in it too. You and I had talked earlier about substance abuse and there’s a scene where he breaks down publicly and I felt there were a lot of personal elements in it. Of course, I didn’t know what went on behind the scenes about the audience testing, but I want you to know that a lot of your intentions actually did come through.

Thank you, that’s nice to hear. I have a very fond memory of the film because of Gwyneth and Ben. Directing Ben was really a joy, because he’s the kind of actor who will do it a million times and be very game and committed and open and willing and ready to go there, and that was a ball for me. And Gwyneth is a deeply admirable person. It was great working with those guys and I’m fond of the movie for that reason. But the film was, for me, an artistic disappointment and it informed my choices over the next couple of years. I didn’t want that to happen again. I’m not really a corporate in-fighter. That just doesn’t appeal to me. You just never win. If I know they don’t want to hear from me, I won’t go there because I find that process very, very painful. To make a film and then have an audience in New Jersey tell me what to do with my baby, I couldn’t handle it. [Miramax] had a little focus group [in which] some idiot in acid-washed jeans stood up and said, “I didn’t like him when he did that.” I felt like saying, “No one has ever lied to you in your life? Someone lied to you when they said you looked good today. People lie.” I didn’t have the balls to say that, or, “Before you take care of my movie, please take care of your hair.”

You’re hilarious.

It’s tough to make movies because they cost so much money so you have to get a lot of people to see them, and I am not a person who loves the American populace. I would be happy if only a few people saw my films, especially the people who need to see my films, like gay teenagers. But it’s a really expensive art form. That’s a real conflict for me.

The hope will be that the DVD market is changing that. I read recently that what’s successful on DVD is not necessarily the big blockbuster, it’s mid-range or low-budget movies, like Happy Endings.

Thank God for DVDs. As a filmmaker, you say that every time you have an opening weekend. Because on DVD, the movie exists in a form that is available to anybody at anytime. That is very encouraging for all of us. Because if you’re like me and you’re writing in order to speak to yourself at a younger age, it’s important to have that available to kids through Blockbuster or Netflix.

It must have seemed logical after your experience with Bounce to go back and do a lower-budget film like Happy Endings.

Absolutely. I wrote Happy Endings, which I finished in July 2002. Because it’s an independent film, very much like The Opposite of Sex and very much in the same genre, I thought in my deluded, egocentric perception of myself that there would be a feeding frenzy for that script. The timing seemed right to me. But nobody wanted to do it. We bounced the project around a bit and then a deal we thought we had fell through. Finally, we ended up at Lions Gate, a studio I did not want to go to because they had blown the release of a movie my boyfriend had written and starred in a couple of years before called All Over the Guy. But we finally ended up at Lions Gate, which made the movie. In that respect, I’m very grateful to them. We had a really magical time making the film. It was the happiest I’ve ever been professionally in my life during the six weeks we shot it. It was great, but the release was an absolute disaster.

Why?

First of all, it was not a summer film, it was a May or September film. But they released it in July opposite Charlie and the Chocolate Factory starring Johnny Depp and Wedding Crashers, the only weekend in the summer that I was afraid of. They opened it in only forty-four theaters and didn’t do any television advertising. They simply didn’t support the film. It was an appalling release. I was never as angry as I was in that summer. There were wonderful reviews, but they wouldn’t take out ads that quoted any of them. It was an appalling, disgraceful, and shameful release. It took a lot out of me. It was a new fear. I’d had fears before: what if I can’t write the script? What if I have no ideas? What if I have an idea but I can’t write the script? What if nobody likes the script? What if nobody wants to act in it? What if nobody wants to make the movie? What if I blow it while making the movie? You have all of those fears. I never had the fear of, what if you make a movie and you love it but the studio blows its release? That had never happened to me. Now I have a new fear about what can happen to you when you make a film. The actual experience of making Happy Endings was truly wonderful, deeply wonderful. Like you said, the DVD market will keep that film alive and available, and in that respect it was a wonderful experience. And studios make mistakes, but the thing is they make mistakes with three years of your life. I’m just emerging from that whole period.

That sounds like it was really painful.

It was painful, but the movie I loved. I never had that experience before of loving something that I made. I think one of the reasons why is because I let go on that film and let the actors be much freer, let the DP [director of photography] be much freer, Clark Mathis, who is a wonderful DP. We all just had a really joyous time making it and I’d never had that experience before.

Even with The Opposite of Sex?

With The Opposite of Sex, I was a nervous wreck. It was my first film and I didn’t know what the hell I was doing.

In Happy Endings, that confidence comes across. It’s interesting that in the script, you seem to arrive at a rethinking of the abortion issue.

I’m always right down the middle of the line about abortion. I’ve no idea which side of myself is right. On one hand, as adoptive parents, as people who require a supply of unwanted or unable-to-be-cared-for children, it would be great if there were no abortions and all of a sudden there were a lot of kids who we could adopt. On the other hand, the idea of society being so invasive into a woman’s life as to say, “You must carry this child,” is so deeply sexist and troubling that I will fight to the death to expand the rights of women to have abortions. What’s happening in this country right now is really just awful—it’s very difficult for people who are not wealthy to get abortions. You have all of these kids who are unwanted being raised, and the cycle continues. The church is involved far too much in this question. But in terms of Happy Endings, it’s not really a rethinking of the issue; just about all of my films have children or pregnant women in them. That’s a very strong and powerful figure for me: a pregnant young woman. Also as a gay man, I feel this kind of camaraderie with women who are being told by straight white men what to do with their bodies. I have felt that oppression and I have felt people who have no understanding of my situation telling me how to do the most important things there are [in life]. Telling me how I can do it, or when I can do it, or that I can’t do it. I’m politically pro-choice, entirely. If you talk to women who’ve had abortions, there is a range of different feelings about it. It’s a huge [decision], but there are many things that we have to have the right to do, even if they trouble us.

Don’t you have a funny story about how the TV reality series Queer Eye for the Straight Guy played a role in your adoption?

We were in the market to adopt a baby. How it happens here in California is you contact a lawyer who has contacts all over the United States and then the women who are pregnant contact him. Our lawyer called us and said this girl’s going to call you. She did and she was a wonderful person. She’s from the Midwest, from a very conservative part of the country, and I was very curious and asked her, “Why do you want to have two gay men raise your child?” She said, “My mom and I just love Queer Eye for the Straight Guy. We think any one of those guys would make a fabulous dad.” I don’t think she said fabulous because I say fabulous and that’s how I tell the story, but it was something along those lines. She said, “Would you mind naming the baby Kyan if it’s a boy?” Kyan is the cute one who does all the grooming. I said, “No, no, sure we will.”

But it was a girl. We named her Eliza.

That’s a great story.

That is an example of the power of media and the power of television to get inside those homes. That didn’t happen to me in the ’50s and the ’60s. I wasn’t receiving any messages from the outside world about being different. I do think people today are able to learn about the world and that there are options through their televisions. I don’t know if we will win or not. The battle will grow larger, and there will be people who will be saved by this knowledge of the world out there. I’m always worried when I hear about gay teens committing suicide. I think we lose a lot of Christian people that way too, because it’s very tough growing up in a Christian family being gay. It’s a funny thing to say, but I do think that the variety of images that television offers young people offers us some hope.

_________________________

FILMOGRAPHY

Happy Endings (feature) (director and writer), 2005

Bounce (feature) (director and writer), 2000

M.Y.O.B. (TV series) (writer), 2000

The Opposite of Sex (feature) (director and writer), 1998

Diabolique (feature) (writer), 1996

Boys on the Side (feature) (writer), 1995

Love Field (feature) (writer), 1992

Single White Female (feature) (writer), 1992

The Colbys (TV series) (writer), 1985-87

Hart to Hart (TV series) (writer), 1979-84

(return to top of story)

_________________________

MORE LAMBDA WINNERS

The Lambda Literary Award winners include A Push and a Shove (Alyson Books), by Christopher Kelly, who is the movie critic for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Kelly’s novel was honored for best gay debut fiction. Here is the complete list of winners:

LGBT anthology

First Person Queer, edited by Richard Labonte and Lawrence Schimel (Arsenal Pulp Press)

LGBT arts and culture

The View From Here by Matthew Hays

(Arsenal Pulp Press)

LGBT children’s/young adult

Hero by Perry Moore

(Hyperion)

LGBT drama/theater

Return to the Caffe Cino, edited by Steve Susoyev and George Birimisa (Moving Finger Press)

LGBT erotica

Homosex, Simon Sheppard

(Running Press)

LGBT nonfiction

Gay Artists in Modern American Culture,

Michael S. Sherry (University of North Carolina Press)

LGBT poetry

Blackbird and Wolf, Henri Cole

(Farrar, Straus & Giroux)

LGBT sci-fi/fantasy/horror

The Dust of Wonderland, Lee Thomas

(Alyson Books)

LGBT studies

Between Women, Sharon Marcus

(Princeton University Press)

Bisexual

Split Screen, Brett Hartinger

(HarperCollins Children’s Books)

Transgender

Transparent, Cris Beam

(Harcourt)

Lesbian debut fiction

Among Other Things, I’ve Taken Up Smoking, Aoibheann Sweeney

(The Penguin Press)

Gay debut fiction

A Push and a Shove, Christopher Kelly

(Alyson Books)

Women’s fiction

The IHOP Papers, Ali Leibegott

(Carroll & Graf)

Women’s romance

Out of Love, KG MacGregor

(Bella Books)

Women’s mystery

Wall of Silence, Gabrielle Goldsby

(Bold Strokes Books)

Women’s memoir/autobiography

And Now We Are Going to Have a Party

Nicola Griffith (Payseur & Schmidt)

Men’s fiction

Call Me By Your Name, Andre Aciman

(Farrar Straus Giroux)

Men’s romance

Changing Tides, Michael Thomas Ford

(Kensington)

Men’s mystery

Murder in the Rue Chartres, Greg Herren

(Alyson Books)

Men’s memoir/biography

Mississippi Sissy, Kevin Sessums

(St. Martin’s Press)

FB Comments