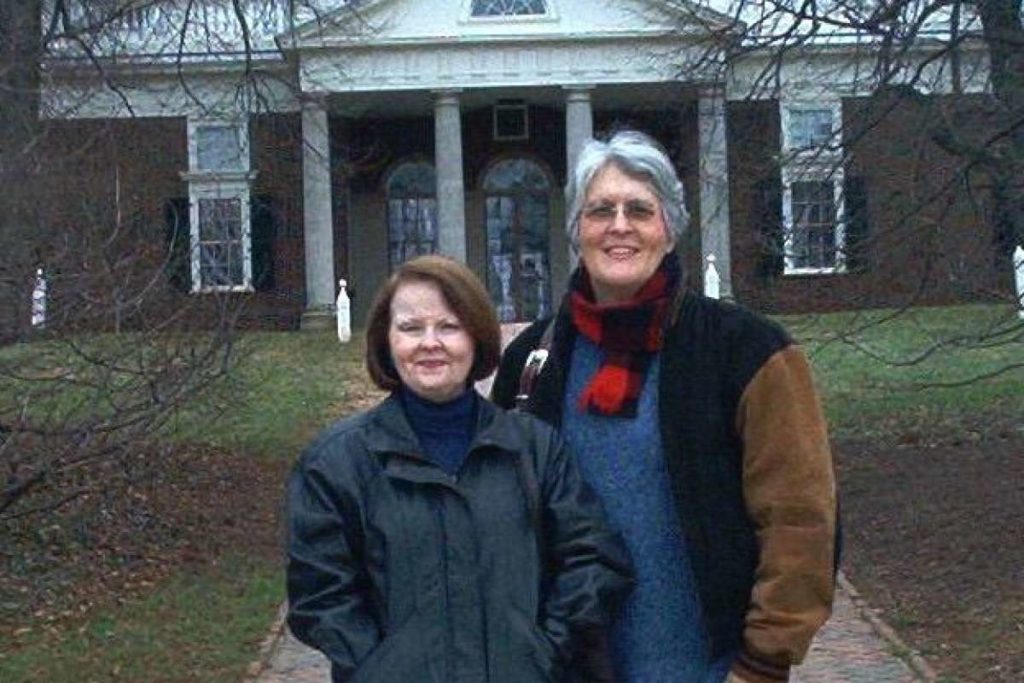

Remembering Patricia “Trish” Frye

A beloved music teacher and quiet presence in the fight for transgender acceptance.

Patricia “Trish” Frye, a 77-year-old retired music teacher, died of brain cancer on September 28. She and her wife, Phyllis Frye, created a historic legacy fighting for transgender rights during their 47-year marriage.

Trish and Phyllis were introduced through a mutual friend in Bryan, Texas, during the fall of 1972. At the time, Trish was a school teacher and Phyllis was an engineer. “Trish was five years older than me and was doing very well,” Phyllis recalls. “She had an apartment, a Mustang, and was under no pressure from her family to marry.”

Phyllis, on the other hand, was hurting. She was a closeted trans woman who had recently been honorably discharged from the Army against her wishes. The pain led her to self-harm. “I was ridden with guilt, had stitches in my wrist, and my first wife was taking my child and divorcing me.”

Despite these emotional difficulties, Phyllis and Trish became good friends and began to date. At the beginning of their relationship, Phyllis tried to repress her gender dysphoria, but it was difficult for her to hide her true self. “I opened up to Trish about it in October of 1972. She responded, ‘I don’t understand all of this, but I’m your friend. Let’s see how it works out,’” Phyllis recalls. Within a few months, the couple was in love.

In February of 1973, Trish told Phyllis, “I’ve looked around and haven’t found anyone else I want to marry. If [your gender identity] is the only thing we have to deal with, I’m getting a bargain.” The two married in June.

“One of the things people overlook about Trish is the amount of courage she possessed,” Phyllis notes. “She was incredibly brave—something that was absolutely necessary, given all of the challenges of our relationship. It would have been easy for her to walk away. She never did.”

While living in Bryan, someone saw Phyllis wearing feminine clothing and reported this to Texas A&M University, which fired her for it. She soon found an engineering job in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where she and Trish lived for a few years. However, she was once again fired after that company learned about her gender identity.

The couple then moved to Houston, where Phyllis worked as a civil engineer for S&B Engineers and Trish taught music at an elementary school in Fort Bend ISD. Feeling more comfortable with life in Houston, Phyllis began to socially transition. In 1976, she told her bosses at S&B that she intended to live as a woman full time, and she was again fired.

Transitioning was difficult for Phyllis, because in those days she was breaking the law by presenting as female in public. Until 1980, Section 28-42.4 of Houston’s Code of Ordinances made it illegal to wear clothing associated with the opposite gender. “When Trish left for work every morning to teach, she had no idea if I was going to be arrested on any given day,” Phyllis says.

While Frye was forced to confront transphobia directly, Trish’s challenges were subtler but no less painful. Trish’s family tried their hardest to break up the relationship. “Her response to them was: ‘Phyllis has done nothing wrong. She’s been entirely truthful to me about who she is.’ Trish would lose most of her family, although they eventually came back to her.”

Trish also had to bear the brunt of continuous cruelty from neighbors who made obscene phone calls and often damaged their property. Her professional life was endangered as well. Working as a music teacher with young children in a notoriously conservative community during the ’70s placed her own employment in constant jeopardy.

“Many of their neighbors were very difficult,” recalls Cristopher Bown, a friend of Trish and Phyllis. “Phyllis, in an effort to ease tensions, decided to [personally] introduce herself to all of them. Trish, who was known for her ability to remain calm under pressure, accompanied her as Phyllis met individuals from every household. That took courage.”

“I don’t really know how she coped with all the emotional and financial challenges of our marriage, but she did,” Phyllis says.

Phyllis’ military benefits included a small stipend for continuing education, so she enrolled in the University of Houston’s law school. But she still struggled to find work after she passed the bar exam, and the majority of her clients came to her with difficult cases that other lawyers were unwilling to touch.

In 1979, Phyllis helped organize the first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. However, neither Phyllis nor any other trans person spoke at the gathering. Phyllis often criticized gay and lesbian groups for not embracing trans people.

Over time, Phyllis became a fixture at the Harris County Courthouse, and was nationally recognized for her work as a transgender lawyer and activist. As her platform grew, she was asked to speak at universities and gatherings, and always made sure that Trish was able to travel with her.

At those events, the spouses of trans people came to her for advice. “She would tell them, ‘You either love this person or you don’t. If you can’t be true to your marriage, get out of it,’” Phyllis says, adding that she has received several communications from people around the world who remembered Trish’s example and her thoughtful advice that helped save their relationships.

In 2010, Houston mayor Annise Parker appointed Phyllis as an associate municipal judge, making her the nation’s first openly trans judge. Trish was extremely proud of her wife’s success, but she preferred to avoid the spotlight.

Bown says Trish “was remarkable in that she always ensured Phyllis was out front, because Phyllis was the one pushing the rock up the hill for the LGBT community. When I would take photographs at various events, I would repeatedly ask Trish to be in the pictures. ‘No,’ she would say, ‘Phyllis is doing all the work. Let her be in the photograph.’”

Charles Spain, a close friend of Trish and Phyllis, recounts, “Trish brought stability to their marriage, in spite of insurmountable challenges. She accomplished that when things were tough, long before the two of them experienced any sort of financial security or professional success.”

Spain worked with Frye on establishing the Texas State Bar’s LGBTQ Law Section, and he met Trish during that lengthy process. “We all knew each other professionally, and then became friends,” Spain says. “Trish, we discovered, had been my husband’s fourth-grade music teacher.”

The two families eventually intertwined, participating in one another’s significant life events. “They threw us an awesome baby shower when our son was born,” Spain says. “They were at my investiture for the Court of Appeals, and also when my son achieved Eagle Scout last year.

“Trish was quiet but very funny, always interjecting various remarks—a complete counterpart to Phyllis,” Spain recalls. Trish’s sense of humor was legendary. On a trip to Paris, while at the Eiffel Tower gift shop she donned a beret and asked her friends, ‘What am I?’ None of them were sure. She responded, ‘I’m a French Frye.’

“Trish’s defining characteristic,” Spain notes, “was this: she always did the right thing. She made the decision to stay with Phyllis and to honor her marriage vows at a time when everyone was telling her to leave. ‘I’m staying,’ she would say. Trish believed in Phyllis, and in what she was trying to accomplish. Without Trish, there would have been no Phyllis. I’m pretty sure Trish was her ultimate counselor who was consulted on every major issue.”

The couple eventually joined their neighborhood’s Westbury Civic Association, and the late gay activist Ray Hill introduced them to the LGBTQ community, Houston’s GLBT Political Caucus, and Resurrection Metropolitan Community Church, where they both joined the choir. The couple was finally finding some much-needed acceptance as they became active in a supportive community.

“Trish’s family came back to us over time,” Phyllis says. “We took care of her mother prior to her death. Trish and her father also reconciled, and her sister was here when she passed. Trish has three adult children and four grandchildren who are all my family—they’ve been very helpful during the last year.”

“Trish accomplished so much in life,” Phyllis concludes. “She taught music to thousands of students during her 52-year career, and was a brilliant teacher. She was a great cook, she always dressed beautifully, she was incredibly affectionate, wonderfully open, an honest communicator, and intensely loyal.

“Trish was my invaluable consort and my best friend. Among the things I will dearly miss is her infectious laugh, and most of all, her distinctly feminine giggle. . . She was simply adorable.”

Comments