African Cosmologies

FotoFest 2020 shines a queer light on the continent.

Vinyl wallpaper

F otoFest’s biennial exhibition is one of Houston’s most internationally beloved and respected art events. Its citywide exhibition venues will once again welcome over 200,000 visitors, including thousands of out-of-town photographic art mavens—so keep your Scruff apps open, and promise me you will show our photography-loving guests some of Texas’ charms. For those of us who live here, the announcement of this mobile museum’s grand themes are always eagerly awaited, as they tend to focus on image makers from far-flung parts of the world. Since its founding in 1983, FotoFest has brought photographic surveys from Latin America, China, Russia, Central and Eastern Europe, Korea, Japan, England, Germany, France, and the Middle East.

FotoFest hires expert guest curators with deep knowledge in particular global practices. The 2018 iteration, with its focus on India, was overwhelming and highly educational. Sunil Gupta, an Indian artist, gay activist, curator, and writer, presented a mind-blowing and challenging lecture on the featured Indian photographers.

I hazard a guess that 90 percent of FotoFest’s featured artists are totally new names for even well-informed visitors. Although many of their names tend to be difficult and “foreign-sounding,” the universal real-world nature of their photographic images requires no translation, even for audiences that know little about the arts and culture of the featured countries.

This year’s FotoFest theme is African Cosmologies, and it is a vast endeavor. The African continent contains so many countries, cultures, and perspectives that inform its many art-making traditions. And with FotoFest’s inclusion of artists from African traditions who were raised in Europe or America, issues of cultural identity get even thicker. I am advising friends to allow days, not hours, to wrestle with the content.

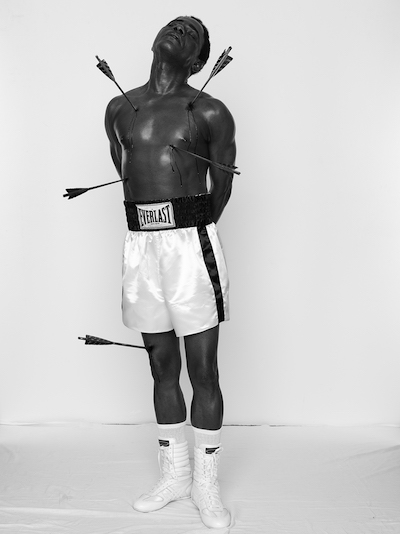

from the series African Spirits, 2008

The African Cosmologies exhibition is being curated by Mark Sealy, director of the world-famous London-based Autograph ABP arts agency dedicated to Black photographers. His 2020 Houston show will examine the relationships between contemporary life in Africa, the African diaspora, and global histories of colonialism, photography, and representation.

Alternative sexualities can be a very fraught topic for experts in African arts, as even progressive thinkers sometimes repeat the false idea that homosexuality was imported from Europe. Thankfully, the younger generation of scholars now understands that what was imported from Europe was its negative attitude toward same-sex relations. While many African cultures were historically neutral regarding homosexuality, the introduction of European homophobia made previously unremarkable sex acts noteworthy.

There are four significant queer artists in this Fotofest: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, Eric Gyamfi, Lyle Ashton Harris, and Zanele Muholi. While not gay-identified, Samuel Fosso employs cross-dressing and gender play in his work. In fact, Fosso (along with Muholi, early Lyle Ashton Harris, and the late Fani-Kayode) are masters of theatrical self-presentation in front of the camera. They create visually stunning fictions to fully manifest collective mythologies, such as when Fosso uses his own body to mimic the iconic 1968 Esquire magazine cover image of Muhammad Ali as the martyred Saint Sebastian. (Africans often witnessed the fate of African-Americans in a racist America through the lens of Muhammad Ali’s triumphs in the boxing ring, followed by the horror of having his title taken from him for refusing to be drafted into the Army—an event that happened in Houston.) Fosso incorporates that history, while adding layers of rich meaning into his visually memorable work.

Muholi, who identifies as non-binary, rose to fame a decade ago for their startlingly assertive portraits of butch women and trans folk in Capetown, some of whom had survived “corrective rape” (in which families hire men to rape the daughters they fear are gay in order to change their sexuality). Today, Muholi is best known for startlingly quirky self-portraits with their hair bedecked with poetic objects. In one archetypal image, we see a shocked Muholi wearing a miner’s hat and goggles, with skin artificially blackened as if covered in coal dust. That self-portrait commemorates the Marikana massacre in 2012, in which 34 striking miners were killed by police.

Untitled, 1987–88

Inkjet print.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode died from AIDS when he was only 34, so his most important works were produced in less than seven wildly productive years. Even though he left Nigeria to escape a civil war when he was only eleven and studied in the United States before settling in England, his work looks conspicuously “African.” Coming from a prominent Yoruba family, his iconography is based on that tribe’s religious ceremonies—what Yoruba priests call “techniques of ecstasy”—and the result is an unforgettably mystical and highly erotic body of works. Despite his early death, Fani-Kayode’s impact as an artist and activist was huge, and he was the founding chair of Autograph ABD that British curator Sealy runs today.

If Fani-Kayode (along with Fosso and Muholi) make constructed images that exist out of the flow of time, the remaining two featured photographers have chosen to embrace the magical quality of documentary photography to capture moments that, in their youthful and joyful exuberance, are evanescent experiences made all the sweeter for their fleeting nature.

Lyle Ashton Harris went back to the pictures of his formative period after college—the period when he stopped trying to “pass” as straight and allowed himself to live as a gay Black man, artist, scholar, and activist. Harris worked in Ghana for a period as a way to fully engage his African origins—an experience that should remind any gay man of the first time he found a loving, supportive, and intellectually stimulating community.

While these four featured artists are widely exhibited in North America and Europe, the great surprise for audiences will be the youthful Eric Gyamfi, who was born in 1990 and is still based in Ghana. Although he is rarely at home in Accra, his creative wellspring remains Ghanaian culture. His series Just Like Us 2016–2019 lovingly documents the daily lives of his queer community, from monogamous long-term couples to his gay and straight friendships—including a look at how Grindr functions in young men’s lives in Africa. In interviews, he speaks about seeing the dominant African culture wanting to make gay lives invisible, so he is determined to prove through photographic evidence that their lives happened, their lives and loves matter, and they deserve to be preserved for posterity.

Indeed, FotoFest should be congratulated for affirming the lives of queer Africans who have made crucial contributions to the continent’s rich culture. For any visitor willing to take the time to learn from the hundreds of FotoFest images, that statement will come through loud and clear.

What: African Cosmologies

When: March 8—April 19

Where: Silver Street and Winter Street Studios as well as other venues citywide.

Info: Fotofest.org

This article appears in the March 2020 edition of OutSmart magazine.

Comments