Capturing a Crisis

Pioneering activist Tori Williams is now working to document Houston AIDS history.

by Andrew Edmonson

When Tori Williams moved to Houston in 1982, she wondered if she’d made a mistake. Watching TV while unpacking, she saw local news reports of the Ku Klux Klan marching on Houston City Hall in protest after mayor Kathy Whitmire appointed Lee Brown as the city’s first African-American police chief. On talk radio, Williams heard male callers saying that they wouldn’t allow African-American officers to pull over their wives.

“My first thought was, ‘What the heck have I done?’” she recalls.

“My first thought was, ‘What the heck have I done?’” she recalls.

Fortunately, she persisted, and Houston’s LGBTQ and HIV/AIDS communities are much richer for her presence. Over the last four decades, Williams has been a quiet but formidable leader, founding three thriving nonprofits, inspiring and mentoring people with HIV to become activists, and providing tireless service to people living with—and dying from—AIDS.

‘An Extremely Clear Vision’

In 1986, at the height of the AIDS crisis, Williams launched Pet Patrol, a nonprofit group that still enables low-income individuals challenged by significant illness to keep their companion pets.

A decade later, she took what she had learned from managing volunteer AIDS care teams and co-founded AssistHers with Renee Tappe. The organization’s mission is to provide a network of support to lesbian women struggling with chronic or disabling illness.

And in 2015, she and Sarah Canby Jackson, archivist for Harris County, co-founded The Oral History Project to collect, preserve, and make available the painful, heroic, and inspiring experiences of people impacted by the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Houston.

In her day job for the last 18 years, Williams has served as director of the Office of Support for the Houston Ryan White Planning Council, helping to disburse federal monies for HIV/AIDS care. In this capacity, she has run Project L.E.A.P., the most comprehensive advocacy training program in the nation for HIV-positive individuals.

“I am fortunate to have Tori’s presence in my life,” says AIDS activist Steven Vargas, a graduate of Project L.E.A.P. who went on to serve as chair of both the Ryan White Planning Council and the Latino HIV Task Force. “I give the majority of my thanks for the work and instruction she has carefully planned over the last two decades.”

In recognition of her service to the LGBTQ community, Williams was named grand marshal of Houston’s Pride parade in 2000. Her girlish charm and low-key charisma belie a laser-like focus and an ability to execute projects swiftly and efficiently.

“Tori always has an extremely clear vision of what she wants, where she wants to go, and how she wants to get there,” says Tappe, co-founder of AssistHers. “When something comes along that might be considered a speed bump, she works around it.”

“She is a professional’s professional, making sure i’s are dotted and t’s are crossed,” says Houston immigration attorney Ann Pinchak, who serves on the board of The Oral History Project. “She keeps people excited about our great work.”

Finding Her Voice

Born in 1954 in Connecticut, she attended the fabled Miss Porter’s School, whose alumna include Gloria Vanderbilt and Lilly Pulitzer. She lived in a room at the school that was previously occupied by one of its most famous graduates, Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis. “The reason that I knew [it was Jackie’s room] is that she scratched her initials on the window,” Williams recalls.

Many might assume that an elite finishing school simply prepares a woman to marry well and raise a family. “What happens in an all-girls school is that girls learn to speak up ➝ and speak out. They learn to do math and science,” recalls Williams. “It’s an environment where women thrive.

“So I graduated from there and went to college at Lawrence University in the Midwest. I was shocked that my Lawrence roommate wouldn’t ask a question in class,” she adds. “I think that I was shocked by them, and they were shocked by me. I realized how lucky I had been to be in an environment where women were treated as smart and purposeful.”

Launching Pet Patrol

After finishing her master’s degree in social work at the University of Wisconsin in 1981, she decamped to Texas to work for Lutheran Refugee Services.

In Houston, she volunteered at a women’s production company specializing in lesbian-themed music, and got to know a wide circle of people. She developed friends in both the feminist movement and the sanctuary movement for Central American refugees.

When gay men in her apartment complex began dying in the mid-1980s, she volunteered for AIDS Foundation Houston, conducting intake interviews to assess patients’ needs. She discovered that if people with AIDS had pets, their top priorities consistently included making sure their animals were taken care of if they became incapacitated.

“So I thought, ‘Well, I can take care of pets.’ I started leaving my phone number and said, ‘If you go into the hospital and need help with your pet, call me.’ And they did.

“Pretty soon, I had lots of calls,” Williams adds. “I started reaching out to my friends—mostly my lesbian friends—and they started taking in lots of cats and dogs.”

One of her friends began referring to the group as the “pet patrol,” and Williams launched a nonprofit using that name and a grant from a local dog-show organization.

“We have one of the biggest dog shows in the world here,” she says. “They had a big dinner, and they raised the money.”

The Pet Patrol included 17 veterinarians who donated time and resources, as well as hundreds of volunteers and, at one point, 400 active clients.

“In Pet Patrol, I went into people’s homes,” Williams says. “That made you understand HIV really fast. I went into homes where you could push the clients over with a feather—where this dog or cat was the longest relationship that they’d had in their lives. They were desperate. The people with AIDS became very isolated and very lonely, and these pets were their lifeline.”

Williams recalls how the first Pet Patrol volunteers often signed up because they didn’t know anyone with HIV, but realized how much their own pets meant to them. “Six months later, these same volunteers would be rabid advocates for their client, whom they now considered to be a valued friend,” she says.

Preserving history

In 2015, the American Academy of HIV Medicine published a report warning that 32 percent of the nation’s HIV clinicians would retire over the next decade. A search of university libraries in the Houston area revealed that they contained no oral histories or theses on the history of AIDS in Harris County.

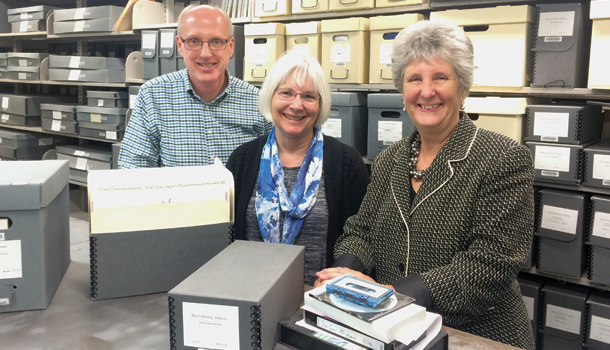

Realizing that the history of the AIDS crisis in Southeast Texas could easily vanish if it was not soon captured, Williams joined forces with Jackson to found The Oral History Project. They set an ambitious goal: to capture 100 oral histories of physicians, activists, political and religious leaders, and others.

Jackson brought Rice University’s prestigious Woodson Research Center to the table so that Rice could serve as the repository for the oral histories, make them available to academics doing research, and feature them online. Williams recruited a cadre of passionate volunteers, and lined up sponsors including Legacy Community Health, the John Steven Kellett Foundation, Gayle and Corvin Alstot, and the Montrose Center (which serves as the fiscal agent for the project).

“My hope for The Oral History Project is that this collection of oral histories will bring understanding and possibly healing in response to what happened, especially during the early years of the AIDS crisis,” Williams says.

“Many of us changed bed linens in the public hospitals, fed patients, and even made sure that people didn’t die alone,” she says. “We have to capture that time to remember, honor those people who went before us, and learn from it. What we learn from the interviews may help us respond more effectively, and more humanely, to a future crisis.”

The Oral History Project is off to a flying start. In early 2017, it was honored by the Houston Press with its prestigious MasterMind Award for its “unique and impressive contributions” to the community.

When she is not volunteering, Williams can be found spending time with a close-knit circle of friends, or curled up in her Heights home watching TV, surrounded by her two cats and two big dogs—all of them rescue animals.

Thirty-five years after her arrival in Texas, her attitude toward the Bayou City has evolved. “I really love Houston, and there’s no other place that I would want to live, ever,” she says. “It’s such an interesting mix of everything and everyone. It’s such a rich place for ideas and people.”

This article appears in the November 2017 edition of OutSmart Magazine.

Comments