Shaping the Gay Rights Struggle

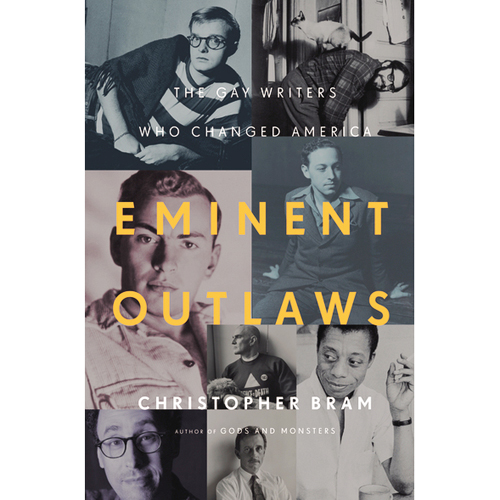

Eminent Outlaws: The gay writers that changed America

Eminent Outlaws: The gay writers that changed America

Be glad that these men took notes

by Kit van Cleave

Eminent Outlaws, Christopher Bram’s lengthy discussion of American gay male writers from the Second World War to the present, suggests that the major thrust of the U.S. gay civil rights movement came from literature—but only from the era he has chosen to cover.

This presents two problems: defining “gay literature,” and ignoring earlier writers whose work may have had equal influence. As for a definition, Bram struggles with this throughout the book, suggesting that a “gay writer” is a gay man whose works deal with homosexuality.

Moreover, Bram’s choice of who was really important during this period seems quite subjective. For example, he writes, “If the central figure for the first half of this book is Gore Vidal . . . then the central figure for the second half could be said to be Edmund White.”

Gore Vidal, called in Time magazine “the best all-around American man of letters since Edmund Wilson,” is a novelist, playwright, screenwriter, essayist, and political activist. White is best known as the author of The Joy of Gay Sex, an imitation of Alex Comfort’s mainstream classic The Joy of Sex.

Who might have been a better choice for the central figure of this period? Tennessee Williams, James Baldwin, Armistead Maupin, Larry Kramer, Edward Albee, and Tony Kushner were all better known, and any of them were more influential than Edmund White.

And what of Oscar Wilde, Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud, Marcel Proust, E.M. Forster, Christopher Isherwood, and W.H. Auden, all of whom wrote openly about gay life? Bram deals only briefly with writers who were gay but didn’t openly bring homosexuality into their works, such as Henry James, Willa Cather, Hart Crane, Thornton Wilder, Walt Whitman, and Gertrude Stein. They could not be open about their sexuality or they would not have been published.

So perhaps the reason Bram chose to limit the time period he examines had more to do with the number of writers whose work could be found and read. Certainly in the early 20th century, most American writers being published were white, straight, and male. Women writers were less well known, and black writers were assumed to have a small audience.

As to the growing interest in constitutional rights for all minorities, perhaps the real acceleration was the revolutionary mood that was a reaction against the conformist 1950s, led by the Beats—Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Jack Kerouac, and William Burroughs. They, like others who had faced the paranoia and intolerance of the American Right, wanted to emphasize the gap between what they had learned in high school and college about the U.S., and the reality of daily life for many minorities, especially blacks.

After the success of the black civil rights movement in the 1960s, the women’s movement developed, then the gay rights movement, and organizations such as La Raza Unida and the Jewish Defense League were formed. Members of these groups were angry at their treatment in the “shining city on the hill” that the Puritans kept mentioning in early American literature. They, too, wanted real equality and opportunity.

Bram’s book is worth reading because of his excellent research and detail; he has clearly scoured through personal papers, knew many of these writers, and read voluminously in gay literature. However, despite the thickness of his book and the number of works and writers he discusses, early on he notes, “This book is about gay male writers and not lesbian writers. . . . [L]esbian literature has its own dynamic and history. It needs its own historian.” Bram might be edified to read the many books, most published in the 1980s, about gay women writers in Paris during the 1920s—Gertrude Stein, Colette, Janet Flanner, Djuna Barnes, Natalie Barney, Renee Vivian, Radclyffe Hall, and many more.

Certainly such a list would include Shari Benstock’s Women of the Left Bank, Andrea Weiss’s Paris Was a Woman (also a film available from Netflix), Richard Ormrod’s bio of Una Troubridge, and the new paperback of Emma Donoghue’s redoubtable Inseparable, reviewed in OutSmart’s February 2012 issue.

Kit van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Montrose. She has published in local, national, and international media.

Comments