Eyewitness

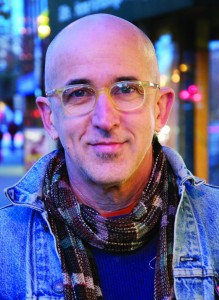

Coinciding with the 30th World AIDS Day, the critically acclaimed documentary We Were Here premieres on PPV and VoD. OutSmart’s Steven Foster talks with the film’s director, David Weissman

It’s been a decade since The Cockettes pranced its way into the multiplex. That film followed the rise and fall of the famed San Francisco drag troupe, a raucous group of cross-dressing misfits who were often high out of their minds as they performed their own unique version of hippie cross-dressing cabaret. Director David Weissman’s next film, arriving 10 years after The Cockettes, is being greeted with even more critical acclaim. And while this film also features San Francisco as its ground zero, its reach is far more global.

With reluctance, Weissman turned his considerable documentary skill toward the tragic beginning of the AIDS crisis with We Were Here, a moving, passionate look at the pandemic through the eyes of five San Franciscans: Paul Boneberg, who has the most activist bent of the five; artist Daniel Goldstein, who himself has survived but lost two partners to the disease; Guy Clark, an African-American owner of a flower shop located in the Castro’s stricken heart; nurse and activist Eileen Glutzner, who participated in the early clinical trials in spite of her mother’s concerns for her own safety; and Ed Wolf, one of the rare members of the tribe who, frankly, was never quite comfortable with the sex-for-all and all-for-sex free-for-all of the times.

This emotionally raw, unassuming, and frank quintet of eyewitnesses puts a far more human spin on the disease and that terrifying, angry era than a thousand interviews with Mathilde Krim could ever accomplish. OutSmart sat down with Weissman to talk about his film as it debuts December 9 on pay-per-view and video-on-demand services, making this important work available to a mass audience.

Steven Foster: Congratulations on the film.

David Weissman: Thank you. It’s been very gratifying. I guess that’s the best word for it.

It’s been about nine years since your last documentary.

Cockettes came out in ’92, so yeah, you’re about right.

That’s a long time to get back in the director’s chair. Why the long wait?

I never know what I’m gonna do next in my life, and I wasn’t really interested in making another documentary after The Cockettes. I was just kind of doing other things, and I guess this idea was just simmering there subconsciously.

The catalyst for you making the film was a conversation you had with your younger boyfriend, isn’t that right?

That was the thing that first started the film going. He heard me talk a lot about my experience in those years, and he just sort of said, “Why don’t you make a movie about it?”

How did you feel about going back to that time? I mean, you were basically right there at the time, front and center with those eyewitnesses who so eloquently center the film.

Mixed. I mean, in a way there was something very empowering about feeling strong enough to do it. It was an affirmation of having moved into a new relationship with that history, and at the same time it was daunting, picking up a lot of sad memories, and a lot of painful memories—not just for myself, but for everyone whom I would converse with about the movie.

The film has many strengths, but the power is in those interviews. There’s no clinician feel to it at all. They seem so intimate and so raw.

I didn’t go into those interviews with any notes, any research, or anything. I went into those interviews with [my experience of having lived] through it. I think what makes the interviews special is that, rather than being conventional “subject/object” interviews, it’s conversations between two people who’ve lived through similar experience. They were kind of mutually therapeutic.

Do you think this generation can grasp the impact of what you lived through back then?

No. I don’t think they can, and I wouldn’t expect them to. And I think one of the things that’s been very powerful with the film is that, without exception, the reaction—particularly from young gay men—has been, “You know, I had no idea.” And I think the film’s been giving them access to that history in a visceral way that’s never been available before.

Why do you think they’re so unaware?

I think that every generation that’s lived through something wishes the subsequent generations would be interested in it, and it doesn’t work that way. I think the generation that stood up on the buses in the civil rights movement feels a disconnect with the younger generation. And I think that’s natural. And I think, in a more specific sense, that those of us who lived through this just wanted to try and put the whole thing behind us as the drugs started to work and the death rate slowed down in the ’90s. There was a desire to find some sort of life that was not completely filled with all this illness and death. And I think there’s a lack of interest in history in this country that’s very pervasive.

And those who aren’t aware of their history are doomed to repeat it.

I’m hoping that the movie will allow for a conversation to begin for people who really haven’t known how to start one.

Do you think a certain level of historical ignorance is typical to America?

[Pause] No. [Laughs] I think we’re worse. I think we have less of an excuse to be historically ignorant.

One of the most striking moments in the film is about the sign that was at 18th and Castro that said, “Be careful guys. Something is out there.” It felt like a horror movie, this unseen killer just out of frame. Do you remember when you were first . . .

I don’t know . . . afraid?

I was there through all of it. I remember those signs in Star Pharmacy. Anyone with any degree of consciousness had to feel the very first twinge of fear. But I think the capacity for denial is enormous. “We have gay mechanics—we now even have our own gay diseases.” There were some jokes at the beginning, but the fear came very, very quickly because the deaths came very, very quickly. Once you knew someone who was sick or someone who died, the terror was profound. And it was a much more homophobic world than we’re living in now, so it was much more terrifying.

One last question, to sort of bring this into the present just a little bit. When the issue wasn’t being addressed—for example, President Reagan never even uttering the word AIDS—there eventually became this incredible activism. ACT UP and the AIDS Quilt. Do you see any correlation between those movements and the current Occupy Wall Street movement?

I don’t know. I don’t wanna . . . I think the Occupy Wall Street thing is just so new, it’s hard to look at it in that kind of political perspective ’til we see where it goes. I think that, for instance during the Viet Nam War, the intensity of the political activism was increased by the fact that people were personally at risk for being drafted into the Army. And I think that that’s something that increases the stakes in political activism. Certainly with AIDS, this incredible crisis, and we were not receiving the kind of attention it would have gotten if it had been feeding on a different population.

Steven Foster is a regular contributor to OutSmart magazine.

Comments