Stand-up Artist

Fortunately, not all of Kelly Faltermayer’s works require him to kneel.

By Brandon Wolf

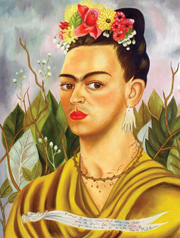

Last November, gay artist Kelly Faltermayer was chosen from nearly 200 applicants to be the featured artist at Houston’s annual Via Colori festival, a celebration of pastel chalk art on concrete. He won the prestigious top billing as a result of his vivid interpretation of a mandrill, a baboon-like primate with colorful facial markings found in tropical rain forests.

Faltermayer delighted early visitors as he created the festival’s large signature artwork on a Saturday morning, layering and blending colors, slowly bringing the animal to life. “It takes strong thighs” he laughs, recalling the creation process.

Faltermayer remembers laughing a lot that weekend. “I met new people and old friends,” he says. “We enjoyed the simplest of life’s pleasures.”

But life hasn’t always been times of laughter for Faltermayer. He was born in 1965 in the poverty-stricken Central American country of El Salvador, a small nation facing the Pacific Ocean. Most of its citizens are descended from Maya Indians, Aztecs, and the Spanish.

Faltermayer’s family lived in the capital city of San Salvador, where his father was a car salesman and his mother worked at a pharmacy. “We were part of a very small middle class. We had a decent home and a car and could actually ride to the local beach,” he says. “We were able to attend school and get a basic education.”

Faltermayer remembers that he played soccer until he was 12, but then dropped out. “I was considered somewhat of an oddity. I knew I was different, but I couldn’t put it into words. I gravitated towards girls as friends. They found me witty and charming and enjoyed my company. I had a great love of beauty and noticed fine details. I expressed this in artwork, but I never shared it with anyone. And I never connected to the dominant macho culture.”

Like many other parts of Central America, Faltermayer’s country was afflicted by warring factions of guerillas. “Different groups rose up to fight against the corrupt government and military,” he says. “Citizens living in poverty felt oppressed by the rich landowners. There were lots of homegrown rebel groups with three initials for names, referring to things like workers, laborers, and liberation.”

Faltermayer remembers the sounds of gunfire in his home city. He regularly heard first-hand accounts of nearby village massacres. “These rebels didn’t have any respect for life or human rights,” he says. By 1977, Faltermayer’s parents began the process of immigrating to the United States, with their eyes on Houston. “They saw no future in their homeland. I probably would have gone insane there.”

New Hope in America

Faltermayer entered the United States in 1980, with the birth name Salvador Bermudez. “I was young, and America was a totally open horizon for me, where dreams could come true,” he recalls.

Faltermayer entered the United States in 1980, with the birth name Salvador Bermudez. “I was young, and America was a totally open horizon for me, where dreams could come true,” he recalls.

He spoke enough English to make it through his freshman year of high school, where he worked hard to improve his fluency and to curb his accent. “You know you’ve mastered a language when you dream in it,” he says. During that freshman year, Faltermayer’s art teacher noticed his artistic talent. “She collected my best artwork and put together a portfolio,” he remembers. “Then she told me she had arranged for an audition at the High School for the Performing and Visual Arts.”

The audition was successful, and Faltermayer completed high school there. Looking back at these high school days, he says, “I had a great sense of wonder. Everything was new—the language, the culture, and the people.”

The next fall, Faltermayer entered the Otis Parsons School of Design in Los Angeles. “I enjoyed having purple hair and listening to the music of Kiss and Adam & the Ants,” he remembers. “I finally had the opportunity to be a rebel.” The financial burden of a college education quickly became prohibitive, however. At the completion of his freshman year, the rebelliousness yielded to practicality.

“I worked as a layout artist for a group of Houston community newspapers for many years,” Faltermayer says, “then I found a job in the art department of a large nutrition enterprise.” He was caught up in the personal computer revolution within the workforce of the 1980s and 1990s. He learned new skills and continued to build an ever-more-impressive portfolio of work.

In 1996, Salvador Bermudez changed his name to Kelly Faltermayer. “I’m not sure where Kelly came from,” he says. “It could have been Jaclyn Smith’s character on Charlie’s Angels. My last name was taken from Harold Faltermeyer, the musical arranger for disco diva Donna Summer. But I got one of the letters wrong!”

In 2004, Faltermayer joined a corporate communications group at AIG Retirement Services, where his duties included the preparation of a monthly magazine. Recently, the economic downturn claimed his job. “It’s good to have a little more time for my art,” he says, contemplating the results of his layoff, “but I really look forward to getting back to work.”

Drawn to Fantasy

Although Faltermayer is a skilled commercial artist, he has always created personal artwork in his free time. “I’m very interested in science fiction fantasy,” he says. “I like the science element—the marvelous possibilities.” Much of the artwork that passes for science fiction these days, he says, really isn’t. “True science fiction is based on science and stays within the boundaries of what might be possible. It is not about outlandish things.”

Although Faltermayer is a skilled commercial artist, he has always created personal artwork in his free time. “I’m very interested in science fiction fantasy,” he says. “I like the science element—the marvelous possibilities.” Much of the artwork that passes for science fiction these days, he says, really isn’t. “True science fiction is based on science and stays within the boundaries of what might be possible. It is not about outlandish things.”

Faltermayer’s examples of true science fiction are Blade Runner and 2001: A Space Odyssey. “It’s possible that all this could happen in the future” he says. “And I love the idea that a man might fall in love with a robot that possesses completely human physical characteristics.”

Sleek technology, beautiful animals, and attractive human beings show up in Faltermayer’s fantasy work. “I love men,” he says. “I like the mathematics of their faces and their bodies.”

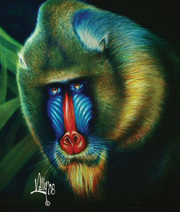

When he creates fantasy portraits, he usually begins with someone he has seen or with a picture in a magazine that appeals to him. “I see amazing lips, eyes, gestures. With the image floating in my head, I begin to highlight the qualities I like the most. I make changes to other characteristics to make them more appealing. I end up with someone who is an ideal. It’s someone who I love to look at.”

Working for a large comic book company like DC or Marvel occurred to Faltermayer. “But I realized that I would be an inker or a colorist of other people’s sketches. I didn’t want to be limited to just one aspect. I wanted to work from original concept to completed piece.”

Establishing Gay Identity

Faltermayer came to America at the crossroads of becoming a man. “I was in high school when I came out,” he says. “I used my school friends as a testing ground. Then I came out to my parents. It was not a surprise for them, and they accepted it because I was their son. I

Faltermayer came to America at the crossroads of becoming a man. “I was in high school when I came out,” he says. “I used my school friends as a testing ground. Then I came out to my parents. It was not a surprise for them, and they accepted it because I was their son. I

tried to explain to them that science shows a genetic basis for homosexuality, but I don’t think they completely understood that.”

Remembering his high school years, Faltermayer says, “They were the best of times and the worst of times. I thought America was welcoming and accepting. But being gay wasn’t a picnic. Not everyone had open arms. It was a difficult reality for a 16-year-old to face. As a teenager, I was often filled with rage, because I couldn’t understand all of it. I couldn’t put the social puzzle together.”

Still, Faltermayer knew that life in Central America as a gay man could have ended in death for him. “Gay men there are looked at as freaks that need to be extinguished. I never had any desire to return to my homeland for that reason.”

Contemplating the issues of gay marriage, Faltermayer says, “The inequities are ludicrous. But culture is what it is, and it will not change overnight.” Still, he’s hopeful when he sees today’s young gays. “Recently, I was driving through Montrose on Fairview, following a pick-up truck. There were two young boys about 15 or 16 in the back of the truck. I could tell they liked each other. Suddenly they reached across to each other and kissed on the lips. It helped me realize how far gay men have come.”

A Life of Exploration

“If I summed my life up in one word, it would be exploration,” Faltermayer reflects. “Understanding life has always been a challenge for me, and I’ve constantly searched for answers.”

“If I summed my life up in one word, it would be exploration,” Faltermayer reflects. “Understanding life has always been a challenge for me, and I’ve constantly searched for answers.”

As a child, Faltermayer remembers being given a white shirt and being taught basic religious prayers. He was then taken to a church for his first communion. “I was just doing what I’d been told to do,” he says. “But it didn’t have any meaning for me. It was just a cultural tradition.”

Lacking religious groundedness, Faltermayer sought for meaning in life elsewhere. “One day at work, someone left a copy of Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged in the employee lounge. I began reading it and couldn’t put it down. It gave me a reason for my rage, and it changed my life,” he says.

He gravitated to Rand’s rational objectivist philosophy, but later realized that her virtue of selfishness lacked compassion. “I left objectivism behind,” he says, “but I also found that I was an individualist, and the most important thing in life was to be true to myself.”

At 44 years of age, Faltermayer believes he is now true to himself—as an artist, as a human being, and as a gay man. “I’ve begun to understand the magnitude of a life—of my life,” he says. “I realize there is always something new to learn, always room for self-correction.”

“Life is a learning process,” he says. “You have to hit the bottom before you learn to look upward. When you’re young, you have to be lost, or else you’re not really trying. You have to experience pain and own it. Life is both agony and glory.”

“Art is a way for me to connect with people,” he explains. “It has been a way for me to make friends since I was in kindergarten, and that has been very fulfilling. The imagery that interests me now is different than what interested me in the 1980s. It is more down to earth and simpler. Via Colori and their conservation theme got me started drawing animals four years ago, treating them like the human fantasy portraits that I have done previously. The beauty that I’ve discovered in animals is a great source of joy, and it’s something I continue to explore. I’ve also begun to do digital illustration, using Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop.”

Kelly Faltermayer will be participating in the 2009 Via Colori, to be held at 110 Bagby, beginning Saturday, November 21, at 10 a.m. and ending Sunday, November 22, at 5 p.m. The free event is held in Sam Houston Park and on the adjoining streets of Allen Parkway and Bagby. More than 175 artists will create colossal-sized works of art, completely created in pastels. Via Colori is presented by El Paso Corporation and Quantum Energy Partners and produced by the Center for Hearing and Speech (CHS). Proceeds from the event support CHS’s mission to teach deaf children to listen, speak, and read. There will be live music, food, and children’s activities. Faltermayer invites OutSmart readers to “stop by and say hello!”

Kelly Faltermayer’s impressive and imaginative corporate portfolio can be viewed on his website at www.kellyfaltermayer.com.

Comments