Mother’s Knock-Kneed Cowboy

When her son came out, this right-leaning mom did the right thing.

By Leigh Bell

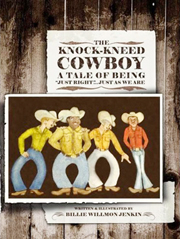

Decades before Billie Willmon Jenkin learned one of her two sons was gay, she often told them a tale of “The Knock-Kneed Cowboy.” It’s a yarn the mother/schoolteacher had been weaving for a while.

Decades before Billie Willmon Jenkin learned one of her two sons was gay, she often told them a tale of “The Knock-Kneed Cowboy.” It’s a yarn the mother/schoolteacher had been weaving for a while.

The knock-kneed cowboy loathed and scorned his come-together legs, desperately wishing them bowlegged, like the other cowboys in town. When Jenkin told the story to her young sons some 30 years ago, in the solitude of their West Texas ranch, that knock-kneed cowboy got his bowed legs, by goodness. But things seemed simpler back then.

Jenkin painted life with a religious-right brush, drawing a box to fit her beliefs nice and neat. She attended church where others felt the same: Don’t question, don’t ask. And homosexuals? They could be “healed” with enough prayer and devotion. Jenkin would later refer to that religious community as “judgmental” and “straight-laced.”

“I raised my boys with those same views, thinking I was protecting them,” Jenkin said, during a talk at a recent Houston PFLAG (Parents, Families & Friends of Lesbians and Gays) meeting. She is now an active member of the group. “This is what I knew.”

Today the oldest boy, Rusty Willmon, is 37 and his younger brother, Trent Willmon, is 36. When Jenkin was raising them, she most feared, “more than anything, except them getting killed in a car accident or something, was that they’d be gay.”

What do they say about our greatest fears? The boys grew up, and although Jenkin didn’t know it, her oldest son, Rusty, was homosexual. He silently feared damnation and shamefully prayed for God to make him straight—much like the knock-kneed cowboy wished for bowed legs, late in the dark of night. Neither wanted to live with their reality.

What do they say about our greatest fears? The boys grew up, and although Jenkin didn’t know it, her oldest son, Rusty, was homosexual. He silently feared damnation and shamefully prayed for God to make him straight—much like the knock-kneed cowboy wished for bowed legs, late in the dark of night. Neither wanted to live with their reality.

Rusty had seriously considered suicide—more than once. Nobody knew. Not his father, not his mother. No one. Life went on.

The boys moved out and into their own lives. Jenkin and her husband eventually divorced after 25 years of marriage. She moved off the ranch and, albeit more slowly, away from the religious right. Then, Jenkin began suspecting Rusty might be gay. What kind of good-looking, charming guy rarely dated or even mentioned girls?

In what Jenkin later admits wasn’t the best judgment, she asked her youngest son, Trent, if his brother was gay. Trent told the truth. That was 16 years ago.

At that moment, “All those old [religious] recordings kicked in,” Jenkin said. She was in the process of lightening and widening her religious beliefs, but those church-talk recordings were deeply imbedded and difficult to kick: homosexuals go to hell. The mother’s to blame. What did the parents do wrong? The list goes on.

“I didn’t understand, but I couldn’t stop loving Rusty,” she said.

Jenkin did have the benefit of sitting with the news without Rusty knowing she knew. She could absorb the idea of a gay son in her own time. But it didn’t take long. Love for Rusty overcame those old recordings. Jenkin wrote him a letter, expressing her acceptance—no matter what. She mailed the letter to Rusty’s San Antonio home, where he lived with his then-partner.

She followed with a visit. Over dinner one night, Rusty told his mother that, yes, he is gay. Jenkin fought off the wedge her son’s admission might have put in their relationship, clearly expressing her love for Rusty. She further proved acceptance when she and Rusty hit the gay bars later that night. There, Jenkin met a preacher’s son whose parents kicked him out when he came out.

“That’s when my heart really began turning away from the religious right,” Jenkin said. “How could someone who preached about an ‘all-loving God’ turn his back on his own son? . . . It was undoing and rewinding those tapes and realizing that there are a lot of things we don’t know, a lot of things yet to learn,” Jenkin said. “I realized that if I—a human parent—loved my son unconditionally, that a Perfect Parent would love His offspring even more.”

It was a profound thought for a woman who had lived so long on the right, but like most realizations do over time, this one lost its profundity. Jenkin was initially thankful to overcome those petrified religious beliefs in order to accept her son’s homosexuality. She was grateful Rusty had managed the same.

“I became complacent about where I was with Rusty,” she said. “I was so happy that I had bridged something in my mind to keep loving Rusty, so I kinda put it on hold.” Kinda like she did the tale of a knock-kneed cowboy.

The next several years were filled with renewals and realizations, as Jenkin came into her own. One of those moments occurred in a seminar on setting and achieving goals, in which Jenkin was inspired to complete her children’s book, The Knock-Kneed Cowboy , the story she told her boys decades ago. She was working on that when Jenkin got a wake-up call. Rusty forwarded her an e-mail he had written to a mother struggling with her son’s homosexuality. In the e-mail to this woman, Rusty stressed the importance of acceptance and underscored his point by admitting he waltzed with suicide. He related how he had courted the notion as a teenager wrestling with his sexuality and what others—God, parents, friends—would think. Twice Rusty had knives at his wrist and once had a shotgun in his mouth, he wrote. He danced cheek to cheek with death.

Reading that e-mail, Jenkin realized that “my words, my attitude, were at the heart of that. Yes, he got them from his peers, too, but it started with me.”

She was shocked—shocked that Rusty was in such turmoil and she had no idea, shocked by the number of kids who must experience what Rusty did growing up. Jenkin’s knowledge of her son’s inner-tussle brought her to a deeper acceptance not only of her son, but of herself and of the world. From that e-mail, Jenkin found her own purpose: accepting herself and helping others do the same.

“If we’re okay at the core of our being, we’re off to a good start,” she said. “And if we see others with compassion, even those who we think are so different from us, then we do ourselves a big favor.”

Acceptance of self and others is now a mission for Jenkin. A self-proclaimed “self-acceptance guru,” she gives influential speeches on acceptance throughout Texas and has written sections in collaborative, inspirational books, including Wake Up Women and Wake Up Moments .

At the heart of her mission, she says, is “how my life turned around through my embracing Rusty being gay.” And so did that story, “The Knock-Kneed Cowboy.” Jenkin completed and published the book, but the conclusion has changed since she spoke the tale to her young boys. The knock-kneed cowboy doesn’t get his bowed legs. Instead, he learns to love his knock-kneed-ness, eventually embracing it.

Wake Up Women, Wake Up Moments, and The Knock-Kneed Cowboy, as well as more information on Jenkin and her cause, can be found at www.empoweringforchange.com.

Leigh Bell wrote about PFLAG Houston for the April issue of OutSmart magazine.

Comments