Many Crowns

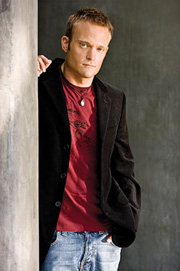

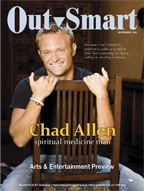

By Blase DiStefano • Cover photo and secondary photo by Greg Gorman

Chad Allen Lazzari and his twin sister, Charity, began their showbiz careers together in local “twin contests,” while still toddlers. Charity didn’t like it much, but Chad liked it a lot. At age four, he dropped the “Lazzari” part of his name, and launched his professional career as child actor Chad Allen, appearing in a McDonald’s ad. Among his many television parts, he had recurring roles in five series, St. Elsewhere, Our House, My Two Dads, Webster, and the series that made him a teen star, Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman.

Today, Chad Allen is an openly gay, deeply spiritual, 34-year-old civil rights activist and recovering addict, with a stable love life and a thriving career which includes producing, acting, and directing across the performing genres of film, television, and theater.

His schedule these days includes a role as a gay private detective in the David Strachey Mystery series based on the novels of Richard Stevenson. He recently appeared at the Pasadena Playhouse in California with Valerie Harper in Looped, a stage play based on one day in the life of Tallulah Bankhead. At press time, Allen was in the midst of filming an episode of CSI: Miami, and in the works is a three-episode arc of a General Hospital nighttime spinoff titled “Night Shift” on SOAPnet, which airs September 23 (2008) at 10 p.m. In the latter, he plays a patient and love interest of an openly gay doctor on the show.

OutSmart talked to Allen about his life and career, particularly about his film, Save Me, which is showing at QFest on September 26 (see QFest: The Best Kept Cinematic Secret in Town). Allen sees the film, which he co-produced as one of the principles of MythGarden Productions, as a dialog between the gay community and straight Christians who sincerely seek to reconcile their faith and understanding of God with their relationships with gay friends and relatives.

Blase DiStefano: I noticed online that you’re doing Looped. How much longer does that go on? [Looped, according to press notes, “is loosely based on the true story of Tallulah Bankhead (played by Valerie Harper), the original celebrity bad girl, who was called into a sound studio to re-record (or “loop”) one line from her final film Die, Die, My Darling. The session was to have taken only five minutes, but instead lasted well over eight hours.]

Chad Allen: We do eight shows a week until August 3. [This interview took place in mid-July, 2008.]

Wow, I feel real lucky that I’m talking to you at all.

[Laughs] I haven’t been awake too long.

You sound a little sleepy. How about we start with Looped? Tell me about working with Valerie Harper. I interviewed her a few years ago and she was one of the nicest people I’ve ever talked to.

She’s incredible. It’s outrageous how incredible she is. My favorite Valerie Harper story is—she hates it that I tell this story but I can’t help it. We were in tech, which is a very difficult process—12-hour days, just she and I onstage the whole time. We were tired and we got a 10-minute break and Valerie disappears and I didn’t know where she went, so I went downstairs to the green room and I heard somebody bustling around in my dressing room, and I thought What’s going on? It was Valerie, and she was cleaning my sink, scrubbing it with a scrub brush, and she went, “Oh, honey, I’m sorry, I brought these cleaning products from home because I thought our sinks really needed to be cleaned better, so I hope you don’t mind I’m cleaning your sink.” I’m like, “Valerie, what are you doing?” She went around and cleaned everybody’s sink. I’m like, “You’re Valerie Harper.”

I took a photo of it and immediately told everybody in the whole theater what she was doing, and she got embarrassed. She was, “Well, I was doing it for myself, so I had to do yours.”

[Both laugh] Now I want to go back to the time you made the film End of the Spear.

I made it four or five years ago. It’s a pretty famous story—I didn’t know that at the time—about a group of missionaries. They were all killed when they attempted to make contact with what we now know to have been the most violent society to ever exist, with the exception of our own. They were a tribe in the Amazon jungle known as the Waodani.

The Waodani had developed a society in which they had no organized system for dealing with conflict. They began almost like family gang warfare where they began killing and killing that went on for generations. They were within a single generation of completely wiping themselves out.

Then these missionaries came and attempted to make contact with them, and they killed the men. But the wives went in after and successfully made contact with the tribe. The generation after that, the tribe had set down their weapons and began to evolve themselves, and their consciousness shifted from killing to peace. I played the leader of the group of missionaries, a jungle pilot. A really interesting experience.

How did you become part of it? Did the director [Jim Hanon] contact you?

I auditioned for it the way actors do. They just felt immediately like I was the guy. And when I discovered who they were—they were Christian filmmakers, and the movie was nonprofit, and they were hoping to make enough money to help put the money back toward helping the tribe, and somebody would go to making other stories with other spiritual messages.

It all sounded good, but I was concerned about the Christian-Right angle of all this and where these guys landed philosophically. I wanted to make sure no money from this film was ever made to hurt anybody or to judge anybody, no matter who they are. I think, unfortunately, we live in a place where God can be used to do that—the religious community can do that, and we know it so well.

When they asked me to come back and meet the producers and directors and talk about making this movie and share very honestly with them about who I was, my solution was then to see how they reacted and go from there. They pulled out The Advocate [with Chad Allen on the cover] and said, “We know and we read the article where you talked about God and spirit, and we feel even more that you’re the right guy for this.” Right away they didn’t conceal they were conflicted over it and that they felt it was definitely an issue they themselves didn’t quite know how to respond to. But they knew I was the guy, and we had to learn from each other and figure out a way to do it and we did.

Impressive.

Yeah. It was a living example of how we were going to try and learn to build bridges and how we were going to live together, and that’s what we did.

That’s really important, because the way we are today—so separated from each other and…

Yes, but it’s changing so much. Now I don’t think we can talk about the issue of homosexuality and Christianity or religion in general without acknowledging the fact there is a large portion of evolving fair-minded Christians. There was a time not that long ago when most people would have said homosexuals and Christians couldn’t sit in the same box, that we were incompatible with each other, and that’s not true anymore.

There is a large movement… in yesterday’s [July 17, 2008] Los Angeles Times I was reading about the latest example about a group here in California of Methodist ministers who walked out in protest saying they consider it a moral obligation to marry gay couples, talking about couples who have been together 30 and 40 years in their own congregation, and they won’t be a part of an establishment that lives in hypocrisy. And that’s just the latest example. In my own experience with the Episcopal Church, a church that I’ve been a member of—All Saints in Pasadena—they’ve been fighting [for marriage equality] for a long time. I’m a member of Soulforce, an organization that exists to stand up against religious bigotry. This is an issue that is changing faster than I can even talk about it, and that is a beautiful thing. Four and eight years ago they were successfully using homosexuality and religion as an issue against us to win elections, and now we’re seeing that shift.

I was blessed to do my part, and that’s the way I see it in terms of making The End of the Spear, and it wasn’t comfortable for me, let me tell you—definitely uncomfortable and confusing and scary. And that in many ways led me to want to make Save Me.

Let’s go on to Save Me. Did the idea start with Craig Chester and Alan Hines or…

No. Alan wasn’t involved. It was Craig Chester’s script, which he had written and almost got produced by Fox. The bottom line is that the script had almost been produced at the studio level and then fell out, because the film But I’m a Cheerleader had come out, and the [Save Me] script was a very over-the-top comedy, a funny, funny script, but not unlike But I’m a Cheerleader. So the studio said they didn’t want to make another one and they let it go. By the time we found it, it was languishing in the middle.

I actually found it because of the work I was doing with a theater company that had it in New York City. I fell in love with it. Robert Gant [Queer as Folk] and Judith Light [Ugly Betty] had come to do a benefit performance for that theater company—where we were reading feature scripts and putting them on stage as kind of a fun twist in the usual way that theater happens—and we all kind of looked at each other and said, “What a great script, we should really do it, it’s a beautiful love story, let’s try and make it.”

So [a group of us including] Christopher Racster, who is my working partner now, had lunch, and we decided we would find a way to make Save Me. We knew we didn’t want to make it as the broad, over-the-top comedy, so we set out finding writers who would re-write it, and that led us to Alan Hines. There were many folks who had their hands on it—we had different directors at different times ultimately. Then we found Robert Cary who was the beautiful, perfect director who made it happen, and we filmed it two years ago.

_________________________________

Comments