Mothers of a Movement

Participants reflect on the groundbreaking 1977 women’s conference in Houston.

By Andrew Edmonson

It was a landmark event for both the women’s and LGBTQ movements in America.

Forty years ago this month, 20,000 women descended on downtown Houston to formulate a plan for advancing gender equality at the National Women’s Conference (NWC). It remains the only national women’s convention to be sponsored by the federal government, and it addressed a dizzying 26 topics ranging from combating domestic violence and improving access to credit, to child care and issues impacting minorities and the elderly.

The four-day November 1977 conference is among three of the most significant feminist gatherings in American history, along with the 1848 convention in Seneca Falls, New York, and the Women’s March of January 21, 2017, when Trump’s inauguration brought millions to the streets throughout the world.

“You could just feel the room and the reaction, and just how powerful the message [was with all of those] women coming together,” state senator Sylvia Garcia (D-Houston) says of the 1977 conference. “It was the first time we had ever done it—or at least in our lifetimes.”

Despite daunting odds, delegates to the National Women’s Conference approved a plank calling for “legislation to eliminate discrimination on the basis of sexual preference and repeal state laws restricting private sexual behavior between consenting adults.”

“It felt as if you were part of one of those moments where you could feel the world changing just a little bit,” says former Houston mayor Annise Parker, who was then a 21-year-old student at Rice University. “The kinds of gains that we’ve achieved since 1977 are the reason that I was able to become mayor.”

The NWC was indeed a turning point in the culture wars that continue today, drawing bright lines around what would become two of the most polarizing issues in American public life: the right of women to access safe and legal abortion, and the struggle for LGBTQ equality. Smithsonian.com has referred to the event as “The 1977 Conference on Women’s Rights that Split America in Two.”

‘The Lavender Menace’

The 1970s was a heady decade for the American women’s movement. In 1972, the Equal Rights Amendment passed Congress overwhelmingly with bipartisan support. President Richard Nixon immediately endorsed the bill.

Inspired by a U.N. conference in Mexico City in 1975 celebrating the International Year of the Woman, Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, established a 35-member commission to make recommendations on promoting gender equality.

In 1977, president Jimmy Carter tapped a commission to organize a national women’s conference, with a series of pre-conferences in all 50 states and several territories, open to all women over the age of 16, to elect delegates to the NWC. The conference’s recommendations for achieving gender equality would be submitted to the president and Congress.

Congress allocated $5 million in support of the project. Houston was selected as the site of the NWC because mayor Fred Hofheinz had established a Women’s Advocate office, one of the first such entities in the nation. Nikki Van Hightower was the second person to hold this position (following Poppy Northcutt), and served as the City’s liaison for the conference.

Congress allocated $5 million in support of the project. Houston was selected as the site of the NWC because mayor Fred Hofheinz had established a Women’s Advocate office, one of the first such entities in the nation. Nikki Van Hightower was the second person to hold this position (following Poppy Northcutt), and served as the City’s liaison for the conference.

But some women still felt like second-class citizens in the American feminist movement. In the late 1960s, Betty Friedan, president of the National Organization of Women (NOW), infamously maligned lesbians as “the lavender menace,” characterizing them as a threat to the success of the women’s movement.

Pokey Anderson was a trailblazing 28-year-old Houston activist who played an extraordinary leadership role. In March 1977, she was a member of the first gay delegation invited to the White House. In June of that year, she was elected co-chairperson of the National Gay Task Force.

Anderson still cringes when she looks back on Friedan’s hostile rhetoric. “Betty Friedan just couldn’t stop talking about why feminism didn’t include lesbians,” Anderson recalls, noting that American novelist Rita Mae Brown had been kicked out of a NOW chapter for being a lesbian.

Parker remembers a fear among some women that their movement would get bogged down in minority issues. “One side of the debate said, ‘Let’s focus on a small number of issues that we can make progress on,’” Parker says. “Others said, ‘No, [minority] issues are fundamental. You can’t pick and choose which rights are important.’”

Out-flanking the Right

Beginning months before the NWC, Anderson and others worked tirelessly to get lesbians elected as delegates, to lay the groundwork for passage of a plank calling for LGBTQ equality, and to raise gay visibility in general. Anderson says Jean O’Leary, founder of Lesbian Feminist Liberation, and Charlotte Bunch, another member of the National Gay Task Force, also played key roles in getting the community organized. “There was no Facebook then, so we used the ‘Lesbian Underground Communication Network,’” she says. “Between Charlotte and Jean, [even Army] generals would be in awe of their prowess.”

Importantly, Anderson says the lesbian community was able to organize without right-wing conservatives taking notice. “The right wing found themselves out-organized, so they set up their own event at the Astro Arena, calling it ‘the real women’s conference,’” she recalls. “They had a big ad in the daily paper talking about how the women at the NWC were going to pervert their children. It was the time of Anita Bryant calling gays ‘human garbage.’ Any hint of acceptance of gay people reeked to the right wing, and they fought back.”

‘The Place Was Pandemonium’

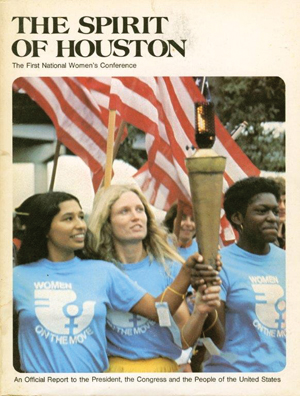

The NWC event opened with a spectacular flourish of pageantry. In the run-up to the convention, a torch was carried by a team of relay runners from Seneca Falls (the site of the first women’s-rights conference) to Houston. Poet Maya Angelou penned A Declaration of Sentiment, which was signed by thousands and presented to first lady Rosalynn Carter and former first ladies Betty Ford and Lady Bird Johnson. The late Barbara Jordan, a daughter of Houston’s Fifth Ward and the first African-American woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives from the South, opened the convention with a rousing keynote address. (Although Jordan was a member of the LGBTQ community, she was not out publicly at the time.)

The array of powerful American women from all walks of life attending the conference included such figures as Friedan, Coretta Scott King, Gloria Steinem, Ann Richards, civil-rights pioneer Carmen Delgado Votaw, actress Jean Stapleton, Lyndon Johnson aide Liz Carpenter, tennis legend Billie Jean King, and Sarah Weddington, the attorney from Roe v. Wade. PBS broadcast the conference nationally, and the documentary Sisters of ’77 was later produced for PBS by Independent Lens.

“I met Bella Abzug, and got to see Gloria Steinem,” Houston transgender activist Phyllis Frye recalls, almost giddy. “It was very empowering. They covered so many different areas.”

Journalist Gabrielle Cosgriff, who covered the conference as a writer and an editor for the feminist publication Breakthrough, says the gay-rights plank was the most contentious, and received a great deal of media attention. “It could also have been a sign of the times,” Cosgriff says. “To my knowledge, that was one area that had not been openly discussed by much of the public before then.”

Frye says it was “a big fight,” recalling that a lot of the women at the conference were “lesbian-friendly.”

“And there were some women who were like, ‘There’s no way we’re going to pass anything to do with lesbians,’” Frye says. “Betty Friedan led the anti-lesbian crowd.”

The most dramatic moment came during floor debate on the gay-rights plank, according to Anderson. “People like Jean O’Leary and Charlotte Bunch had talked about who should speak on the floor, and who we should have on our side speak,” she recalls. “People were pinpointed, and it was agreed who should be at the mic to be able to speak.

“At that time, Betty Friedan got up to speak,” Anderson adds. “My heart sank. I thought, ‘How did Betty Friedan get a place at the mic to speak? We’re going to lose.’ What I didn’t know was that she had agreed that it was time to put this division behind us. Some friend of hers had taken her aside. They’d had a good conversation, and she was okay.”

The tape of Friedan’s speech still gives Anderson chills when she hears it. “Here is one of our most high-profile opponents in our own feminist movement, and she comes over to our side,” she says.

Cosgriff says after seeing the “enormous spectrum” of conference attendees, “it was obvious to all that our goal was not to exclude any woman from realizing her potential.” The vote was overwhelmingly in favor of a plan that included the gay-rights plank, according to Anderson.

“The place went up in cheers and applause,” Anderson says. “There were thousands of women in the hall. The chair kept having to say, ‘Order! We need order!’ The place was pandemonium. Women were crying. Women were dancing on the chairs.”

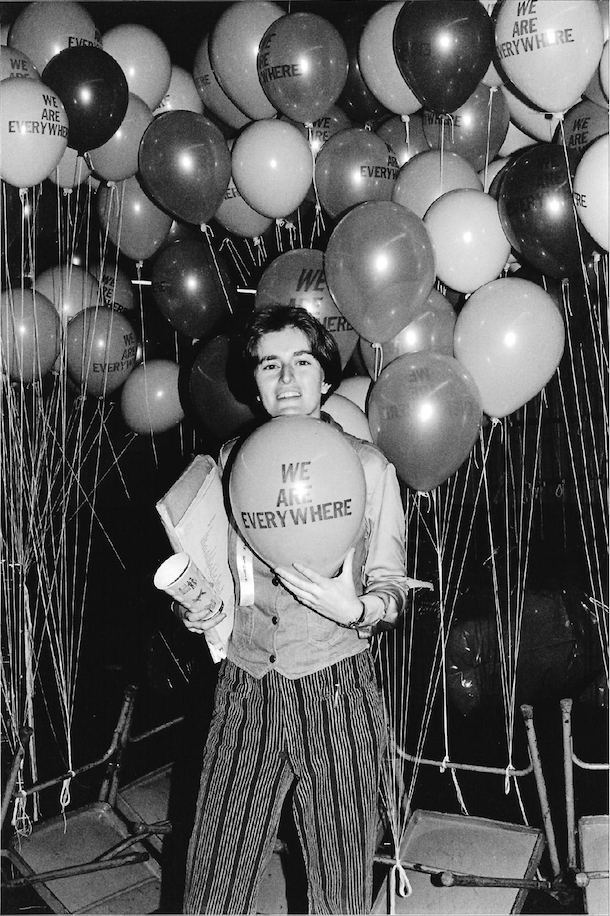

Balloons declaring “We are everywhere” were released, floating up to the rafters.

The Pace of Progress

Memories of the conference are bittersweet for some attendees.

Katy Caldwell, CEO of Legacy Community Health, had volunteered as a 21-year-old student at the University of Houston. “I think it galvanized a lot of people around women’s rights. Looking back, the platform was incredibly progressive,” Caldwell says. “It galvanized a lot of people, both for and against the Equal Rights Amendment [ERA].”

In assessing the event, she sees obvious victories for women that sprang directly from the 26-point plan approved by delegates. “We have more minority- and women-owned businesses because of what happened at the conference. We have greater representation of women in federal arts and humanities programs,” Caldwell says. “It got more women to run for office than had ever run before. We’ve come a long way in dealing with victims of domestic violence—although there’s still work to be done.”

But there were also defeats that sting to this day. “We didn’t pass the Equal Rights Amendment,” Caldwell says. “While women have more access to government contracts and business, we still struggle with Roe v. Wade. We still don’t have equal pay.”

It’s a “depressing” reality, Caldwell says, and many women her age have grown weary of the fight. “I remember apologizing to my niece at the Women’s March [last January], saying, ‘I’m sorry that you’re still having to do this. I cannot believe that you all have to be here,’” she says.

Commemorating History

For Parker, the impact of the 1977 conference came full-circle a few years ago when she attended a luncheon with Gloria Steinem, who was in Houston for the first time since the NWC. “I told her that I had been a volunteer, and it had been a great experience for me,” Parker says. “She said, ‘Is there anything that commemorates it?’”

When Parker told Steinem that the old convention center and coliseum where the conference was held no longer exist, she responded, “That’s a shame. There ought to be something to designate what happened there.”

“I said to her, ‘As mayor, I can take care of that,’” Parker says, adding that she had a historical marker commissioned and installed at the site of the NWC event, across from City Hall. “I sent her a nice little note thanking her for saying something,” Parker says. “Before I left office, I wanted to make sure that we acknowledged it.”•

This article drew significantly on the research done by LGBT historian JD Doyle and the website HoustonLGBTHistory.org, which he curates.

Comments