In the Doing

‘Victory’ tells us where we’ve been, where we’re going, and why it all fits together

by Kit van Cleave

Sometimes an author can write such a comprehensive book that any attempt by future authors to cover the topic may seem like an afterthought.

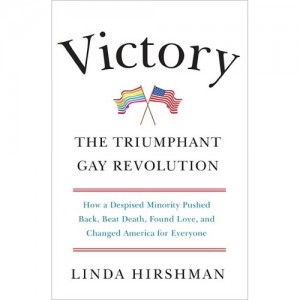

Linda Hirshman’s Victory: The Triumphant Gay Revolution is one of these books. With careful research, Hirshman, a lawyer who also holds a PhD in philosophy, shows why the gay rights movement has accomplished many of its goals, and outlines a template for how to continue a successful revolution.

In doing so, she creates an historical reference work that will surely be read by groups involved in the gay struggle for full equality. But Victory will also serve as a history book for younger Americans wanting a broad-brush look at the entire American civil rights movement.

The first recognition, she says, must be of the concept of “other,” meaning any person who is so far removed from oneself that the distance cannot be overcome. As conservative reaction to the first African-American president has shown, regarding someone as “other” is a major obstacle to broad-based acceptance by citizens.

Hirshman starts with the black civil rights movement, in which skin color and facial features prevent people from attaining full rights. Unless this disunifying “other” is recognized and overcome, America may never again have a president who is not white, Christian, straight, wealthy, and male.

At the dawn of the 20th century, in a country largely white and increasingly evangelical (though declining in church attendance), gays were simply seen as unacceptable. They were called sinful, perverted, crazy, and criminal; any avenue leading to civil rights in a democracy was closed to them. Those taking the first steps to equality did not see this seminal point—they were just resisting the injustice of repeated arrests, beatings, social rejection, and various forms of imprisonment.

The initial connection between the gay movement and Communism was due to an observation by gay-movement founder Harry Hay and others that during the early days of black assertiveness, “the only people doing anything to help” were Communists. “When like-minded people come together, sometimes they are liberated to act to release their underlying feelings in ways they would never do alone,” Hirshman writes. Both the Communists and the oppressed in America were like-minded in their drive for opportunity, justice, and equality.

Obviously, this connection would be exploited during the years of Senator McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Not only were both Communists and homosexuals denied the right to serve in the military, but they were also denied federal jobs.

Hay recognized Stalin’s definition of a nation as having a stable community of people, a common vernacular language, occupying a single piece of territory, with an integrated, coherent economy, and a unified psychological makeup (a folk psychology or national character).

“Once the Communist ideology machine recognized the special place of the oppressed Negro minority in the human liberation project, the way was opened for other American identity groups,” Hirshman points out. The country started seeing ongoing attempts to liberalize the social contract between oppressed citizens and those who did not recognize them as equals.

Many gay people don’t realize that police were raiding New York bathhouses as early as 1903, or that there was no clear definition of “homosexual.” Hirshman walks the reader through Mafia-owned bars, therapists trying to change gay people, and the effects of the Second World War draft as a great equalizing force among social classes.

During the draft, doctors would ask a recruit, “Are you gay?” and reject anyone who didn’t answer or hesitated. Straight black men were also found “unfit for service.” Women who courageously volunteered for the war effort were called lesbians and then discharged when they did not welcome sexual overtures. Then came the Kinsey Report of 1948, opening up a national discussion of sex—especially women’s sexual habits and homosexuality—citing statistics that 37 percent of American men had had at least one homosexual experience.

Slowly, the bond of oppression was forming in the 1920s and 1930s among blacks, gays, and women. (During the 1960s and ’70s, these connections would become invaluable.) The history of revolutionary clashes continued with the treatment of Jews and the incarceration of Japanese-Americans during WWII, the demonization of immigrants, and the present-day “99 percent vs. 1 percent” protests.

Income inequality and suppression of the vote since 2000 have increased as wealthy conservatives try to stop further intrusion by minorities into their areas of control.

Hirshman is particularly good at naming the heroes of various movements through the years—such as the first people to protest the Army-McCarthy Hearings, the exclusion of gays from federal jobs, and the denial of AIDS by Ronald Reagan and others. Do you know which gay Ivy-League lawyers came forward to volunteer their time to fight DOMA or DADT? One of the book’s not-to-be-missed moments is the account of the white males from affluent families and the best schools, who were used to being treated as superior humans, who found themselves seen as “other” due to being gay. Their outrage has fueled much recent hard work for equality and justice.

While her book is titled Victory, Hirshman notes in her epilogue, “Of course there is a lot left to be done,” reporting that presently in the upper Midwest, 28 states have no affirmative laws or other evidence of gay victory. But, she adds, gays must push on, since “the victory is in the doing. In doing the work, gay activists ennoble themselves, and by proxy, other people in their community.”

Victory includes an historical timeline, full notes, a lengthy bibliography, and references to websites and online blog posts. Moreover, it’s entertaining to read. Please do.

Kit van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Montrose. She has published in local, national, and international media.

Comments