Get the Scissors

Augusten Burroughs’s self-help follow-up falls short of his first effort

by Kit van Cleave

In the literary business—where ideas or stories are translated into words to be printed—legend has long had it there are two kinds of writers.

There are the supremely gifted ones who produce sporadic works because their lives take up a lot of creative time. These writers are searching for enlightenment, excitement, and ecstasy, sometimes through addiction.

The other group is obsessed with writing as much as possible; their lives are all about work and publishing. Writers such as James Patterson and Joyce Carol Oates typically finish one book and quickly start another.

Today’s technological advances haven’t changed this legend much, though more people are writing—and writing, and writing. Everyone who has a blog thinks the world is waiting to read it, but blogging is no more a path to celebrity or self-expression than a mediocre book in hardcover. Facebook and Myspace have encouraged people to tell about what they had for breakfast, how they slept (and with whom), and their crises. But it’s not literature.

What, then, motivates a well-known writer to dash off a book telling others how to “get it together”? Especially when the sentences don’t show much polish, and the ideas are mundane?

In the writing biz, as in professional gambling, it only takes one really successful book to make a career. Sometimes a writer can live for years off of one book’s touring and lecture opportunities. Even so, his publisher and agent will continue to hound him for another book, as soon as possible, for that’s how they make their money.

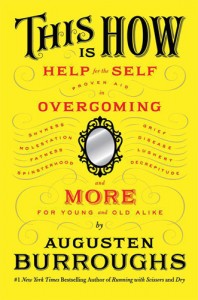

Along comes Christopher Robison (who legally changed his name to Augusten Burroughs when he was 18) without any medical credentials, or even a psychology class or two (he earned a GED at 17) to give advice for better living. In fact, the subtitle of his new book, This Is How, is “Help for the Self, Proven Aid in Overcoming Shyness, Molestation, Fatness, Spinsterhood, Grief, Disease, Lushery, Decrepitude, and More for Young and Old Alike.”

Along comes Christopher Robison (who legally changed his name to Augusten Burroughs when he was 18) without any medical credentials, or even a psychology class or two (he earned a GED at 17) to give advice for better living. In fact, the subtitle of his new book, This Is How, is “Help for the Self, Proven Aid in Overcoming Shyness, Molestation, Fatness, Spinsterhood, Grief, Disease, Lushery, Decrepitude, and More for Young and Old Alike.”

Of all the sad childhoods in American history, Burroughs certainly had one for the record books. His father was the alcoholic John G. Robison, head of the philosophy department at University of Massachusetts Amherst. His mother, Margaret, a poet and writer, was diagnosed as “manic-depressive” or “bipolar.”

Perhaps Margaret Robison saw herself as an obsessive writer, since she had hopes of writing in the style of Anne Sexton. Apparently her drive to write didn’t leave her much time for mothering, as she “farmed out [her son] to his mother’s psychiatrist, a deeply disturbed—and disturbing—man whose medical license was ultimately revoked for gross misconduct,” according to Barnes & Noble’s “Meet the Writers” website.

Most of Burroughs’s childhood memories were set down in Running with Scissors (2002), a widely read and praised bestseller variously called a novel, a memoir, and pure fiction. He recounts living with a “family” headed by his mother’s psychiatrist in “an experience tantamount to being raised by wolves,” according to the website.

“The characters he describes are unforgettable, children of assorted ages running wild through a filthy, dilapidated Victorian house, totally unfettered by rules or inhibitions, a variety of detrained patients who take up residence…seemingly at will.”

Moreover, a 33-year-old pedophile who lived in a backyard shed “initiates an intense, openly homosexual relationship with the 13-year-old right under the doctor’s nose.” Undoubtedly, the chaos and trauma of these experiences led not only to Burroughs’s alcoholism, but his coming out in print as well. But they make him neither a psychologist nor a philosopher.

For example, the chapter “How to Find Love” includes this advice: “The truth is, most people you meet are totally wrong for you, whether you meet them online or at an after-party for the Oscars. Which is why meeting truckloads of people is almost a requirement. It doesn’t matter how many ‘wrong’ people you meet; what matters is doing everything possible to meet that one person. Don’t try a new venue—like online dating—thinking you’ll meet ‘better’ people; try a new venue because you’ll meet more people. It’s like with diamonds. It can take more than 200 tons of ore to yield one high-quality diamond. Nobody is obsessing over all this ore; they’re focused on that diamond.” Hmmmmm…

From “How to Get the Job”: “During an interview, candor and transparency matter almost more than sheer ability. Skills can be learned, but if your body is shifty, there you go. They’re shifty and can’t be trusted, period.

“Most everybody is nervous during a job interview. And for the person conducting the interview, it’s frustrating because you just wish you could meet the person who would be coming to work every day instead of the job-interview-version of this person, on their best job-interview behavior.” What?

While I admire Burroughs’s survival ability and continuing desire to write, this book retails for $24.99. Probably best to put that in a jar in the closet to save up for a conference with a legitimate therapist who has the background and technique to hear you out and actually help you solve your troubles.

As Burroughs would say (or write), “There you go.”

Kit van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Montrose. She has published in local, national, and international media.

This Is How

By Augusten Burroughs

2012, St. Martin’s Press

(us.macmillan.com/SMP.aspx)

240 pages, $24.99

Comments