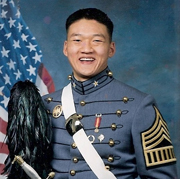

Lt. Daniel Choi takes on Congress and the U.S. military

By Brandon Wolf

Photo by Tanya Dodd-Hise

On March 19, 2009, Lt. Daniel Choi, a West Point graduate and a veteran of the Iraq war, appeared on national television on The Rachel Maddow Show. Meticulously groomed and exhibiting a confident military bearing edged with calm defiance, the handsome young officer looked into the television camera and uttered three words that changed the entire course of his life—“I am gay.” Still an active-duty soldier at the time, Choi defied the military by publicly disclosing his sexual orientation.

Propelled into the international news spotlight by this very public disclosure, Choi established his role as one of today’s leading gay activists. As simple as the public declaration of his homosexuality appeared, it was the culmination of nearly three decades of remarkable achievements—most of which he accomplished while living in extreme emotional isolation.

Lt. Choi recently talked with OutSmart, giving us an exclusive look at the personal journey that brought him to the point where he is today. Reflecting on the loneliness he experienced on that journey and exploring a past that had long remained repressed, Choi comments that the interview was “cathartic.” The accomplished man who emerges during this interview makes the military’s ban on homosexuals seem especially ludicrous. Clearly it is not in our national interest to drive “the best and the brightest” from military service. In the case of Lt. Choi, however, the Army’s loss is the gay community’s gain, giving us a courageous and passionate leader who is fearless and determined in the face of adversity.

The Boy from California

Daniel Choi was born in 1981 in Orange County, California, an area between Los Angeles and San Diego known for its conservative mindset. Much of the funding for Proposition 8 in 2008 came from its citizenry.

Choi remembers his southern California childhood, growing up in a household with his parents, older brother and younger sister, and his grandmother who spoke only Korean. Choi’s parents were South Korean immigrants who met and married in the United States. Growing up during the Korean War, both had felt the sting of conflict. Choi’s mother has no idea what became of her father—he was “stolen away into North Korea”—and his father, too, experienced the mysterious disappearance of relatives.

As a Korean Baptist minister, Choi’s father was often transferred within the southern California region to start new churches. “I went to five different elementary schools,” Choi says, “but I was able to attend the same junior high school and the same high school.”

The young Choi especially loved music, and his mother arranged for piano lessons. “I think my parents hoped I would become a pianist and choir director for their church, but I rebelled.” Following his own interests, he took up the trumpet. “But when I got braces, I had to switch to a tuba. I also dabbled with the flute, clarinet, and violin.”

As early as the fourth grade, Choi says, he felt attracted to other males, but at the church his father pastored, he heard only negative things about gays. “They didn’t talk about it much, but when they did, they said that gay men wore lipstick and high heels, that they all had AIDS, that they molested children, and that they lived in dirty places like San Francisco.” Then he adds with a chuckle, “and places like Houston.”

In addition, his brother was homophobic. “At school, there was one boy who was openly gay, and I couldn’t imagine being open like that. We joked about him, but years later when those of us who were gay looked back, we admired him.”

“I didn’t want to be a stereotypical homosexual,” Choi says. “And I especially didn’t want to be an effeminate Asian man. This made the military even more attractive because it was so masculine.”

High school was a busy time for Choi. He was involved with the swim team, the marching band, student government, and a youth band not associated with the school. He participated in the American Legion’s California Boys State program and Model United Nations conferences. Fortunately, he lived right across the street from his high school.

His involvement with the school band meant he had to attend a late-summer band camp. “Sc hool started early for me,” he says, “but I enjoyed the discipline and the regimentation.”

During his junior year he was a member of the student government, assigned to be the club commissioner. His greatest achievement that year was organizing a multicultural week at the school. “The faculty complained that there were too many assemblies, because each ethnic group wanted their own day. I had to convince everyone to take part in a combined event. It wasn’t real popular, and I ended up giving my first sound bite to the media during that time—explaining why it was a good idea.”

At the end of his junior year, Choi took part in a weeklong tryout for drum major and won the job. “I had to be able to give vocal commands, keep the time, and conduct the band on the ground.” He also had to learn how to twirl a baton. “That sounds so gay, doesn’t it?” he laughs. “But it was a mace—a military baton—not like a majorette’s. It’s not flamboyant, but it involves technique.”

Choi was elected student council president in his senior year. “I always hung out with the less popular students, and they ended up putting me into office. I’m sure most of the band also voted for me.”

“I woke up at 4 a.m. to go to varsity swim team practice. That was followed by band practice,” Choi remembers. “Then I had a full course load, because I was in advanced placement. At 3 p.m., there was a student government meeting, which was often followed by meetings on specific issues. I usually got home at 7 p.m. and did my homework. The only television show I allowed myself was The Simpsons.”

Choi admits he had crushes on men during high school, “but I kept busy all the time so I wouldn’t have to deal with it.” Still, despite his impressive achievements and popularity, Choi never had a girlfriend. Although he had convinced his family and his peers that he was happy and involved, he couldn’t convince himself. “Sometimes I was so lonely, I would cry my eyes out,” he says.

Preparing for a Military Career

“I didn’t have a G.I. Joe action figure as a child, and never played soldier,” Choi says. “I never romanticized the military.”

His father had been a member of the South Korean military—a member of the military police and the honor guard—and had hoped to attend the Korean equivalent of West Point. The director of the youth band Choi had joined was also a military man and a World War II veteran. “Our band folders were all from the Marine Band,” Choi remembers.

While at a California Boys State event, he heard speakers from West Point talk about leadership in the military. “I saw the importance of serving something larger than myself,” Choi says. “Putting your life on the line was the most visible way to do that.”

After his junior year of high school, Choi applied to West Point, the Naval Academy, and the Air Force Academy. He had seen the film Saving Private Ryan, and it had provided the final impetus to pursue a military career.

In the fall of his senior year, an envelope arrived from West Point announcing Choi’s acceptance. His mother was not happy with the news. “She thought I would be killed. She wanted me to stay home and marry a Korean girl. She wouldn’t pay for the application fees to the military academies.” Nevertheless, West Point had been his first choice, and he was pleased.

In the fall of 1999, Choi set foot on the grounds of West Point for the first time. “But I wasn’t able to enjoy the beauty of the campus at first; I was totally focused on finishing. There is a very high attrition rate the first year. From the initial class of 1,500, usually 600 drop out.”

A key component of entering West Point is boot camp, with a strong emphasis on West Point values. “It was a challenge; I lost weight,” Choi says, “but I liked being pushed physically and emotionally.” In addition to the physical challenges, boot camp included memorizing General MacArthur speeches and learning the history of West Point and war.

“Every cadet at West Point earns a bachelor of science degree,” Choi explains. “It was engineering-oriented, so there was a lot of physics, chemistry, calculus, math, probability, and statistics.” His course load also included classes as diverse as poetry, military strategy, gymnastics, and boxing.

Choi joined the West Point marching band and was the leader of the bass section of the Chapel Choir. The band played at the Army-Navy game, and the Chapel Choir had an outreach program that included such venues as Sing Sing Prison.

Language study began in his sophomore year, and Choi chose Arabic. “It’s the language spoken in Jerusalem, and I had heard many stories about my father’s visits to that city, so I wanted to learn their language. I was also aware of the strategic relevance of the language, considering current events of the time.” Choi was one of only eight cadets who elected Arabic, and he finished first in his class.

By his senior year, Choi was chosen to be the cadet in charge of West Point dress parades. “The faculty monitored the parades, but they were entirely run by the cadets,” he says.

Graduation week in the spring of 2003 was exhausting for Choi. “I was in charge of all the parades, and there was one each day. In addition, my parents had flown in for the ceremonies, and I was packing to head to Fort Benning for officer training.”

Deployment in Iraq

Choi spent the next two years in a variety of special military training centers. He became proficient in such activities as parachuting, air assault, and survival ›

training. At Fort Drum, New York, he underwent winter training, sometimes in 30-below temperatures.

He learned about transportation and logistics and how to lead a unit through combat. Despite the rigors of the training, he found it slow compared to high school and West Point, so he was pleased when he was asked to teach Arabic to 800 soldiers in his battalion. Soon his life once again started at 5 a.m. and ended at 9 p.m.

“People think that when you graduate with a language degree from West Point, you are fluent in the language, but that’s not the case,” Choi says. Determined to improve his fluency, he visited local mosques and sought out other opportunities where he could practice the Arabic

language.

In 2006, Choi and his troops were sent to Iraq. They landed in Kuwait and were then sent to south Baghdad, near the airport. “We were in a buffer area between the Shiites and the Sunnis. It was known as ‘the triangle of death,’” he recalls. In the 15 months that his brigade was stationed there, they lost more than 60 members.

“There is no such thing as an officer who is a translator,” says Choi, clarifying a misconception about his duties in Iraq. “I was an infantry officer, and my job was to patrol the area 360 degrees and provide logistical leadership. There is no real invading line after you’re the occupying force.”

Because he was proficient in Arabic, however, he was often called upon to translate. “There were a lot of stressful moments,” he remembers. “Sometimes we blew up the wrong houses. I was the one who got an earful from the tribal leaders and the village wives. It’s one thing to hear what a tribal leader says through a translator, because it’s stated diplomatically; it’s quite another thing when you’re being called a lifeless, soulless bastard.”

“Iraq was a counterinsurgency, and we were right in the middle of it,” Choi says. “In that sense, it was very similar to Vietnam.” One of the major responsibilities of his brigade was to uncover improvised explosive devices (IEDs). “The IEDs could be anywhere—under a pile of trash or inside a dead dog. Just about every other day, we would lose a vehicle.”

Local Iraqis quickly took a liking to Choi. “They wanted me to stay and marry an Iraqi girl and become part of their tribes.” In mid-2007, Choi returned to the United States. “But I felt I hadn’t done enough. I knew so many people who had come back blind or without limbs.”

In exchange for a West Point education, Choi had a five-year contract with the military. That obligation was fulfilled in 2008, and he decided to resign. Upon leaving active duty, he was given 50-percent disability because of a respiratory condition that developed in Iraq. “I also had a long history of broken bones,” Choi says. “They take your whole medical history into account when determining your health status.”

Choi still had an obligation to serve in the National Guard, and he was assigned to the First Battalion, 69th Infantry Regiment, based in Manhattan. He returned to California to live with his parents and flew to New York once a month for a four-day weekend with the Guard.

Emerging from the Closet

While he was at West Point, the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy actually kept Choi from exploring his sexuality. “Now I look on it as a lie, but back then it was a necessity.” He didn’t know anyone at West Point who was gay, and didn’t want to. “It would have been a slippery slope,” he says. He did discover that the leader of his high school youth band was gay, and confided in him. “But it was ultra-secret.”

After graduating from West Point, Choi finally had his first sexual experience with another man. “We met on the gay beach in Palm Beach,” he says. He remembers visiting a bar named Christopher Street, but was paranoid the entire time. “I was afraid I had been followed.”

During his five years in the military, Choi never knew anyone gay, and he continued to repress his feelings. “I stayed busy because it was a good excuse for not having

a relationship of any sort.”

In 2008, Choi met Matthew Kinsey in a New York club and fell in love. “I finally decided it was time for me to live,” he says. Although they are no longer partners, they remain close friends. That relationship became the determining factor in his decision to leave the military. “I felt I couldn’t have the relationship and stay on active duty.” His relationship with Kinsey emboldened him to a degree, but he was still worried and cautious.

Choi’s defining moment came the day after Barack Obama’s election. “I discovered that Proposition 8 had passed in California. I saw the news coverage of demonstrators who were protesting its passage, and I felt guilty that I wasn’t doing something.”

Choi decided the first step would have to be coming out to his parents. He told his mother first, explaining that women didn’t stimulate him sexually. “I told her that I had picked Michelle Pfeiffer as a sexual fantasy and nothing happened. She told me that I should have chosen a Korean girl and then things would have worked.”

When their discussion became loud, his father came into the room. When he heard the news, he said in bewilderment, “No one in our family has ever been gay. How can you be gay? You’re in the military—you’re so manly.”

Choi even temporarily split with his partner Matthew and never introduced him to his family. “I didn’t want them to blame him.” But once the long-repressed secret was out, Choi found that his sister supported him, and his brother changed his attitude about gays. “I sent him a Facebook message telling him I was gay,” he laughs.

No longer limited by the family closet, Choi joined the Gay Men’s Chorus. “It was wonderful,” he says. “I was amazed to meet so many nice gay men. It was very different than the bars.”

Choi also began to network with a group of West Point graduates who were gay. It was a secret society, but the members of the network wanted to become more public. Once again, utilizing his instinctual sense of leadership, Choi founded Knights Out, a group of out West Point graduates and their straight supporters.

The group wanted to do something about Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, but none of them had remained on active duty. That left Choi as the only member of the group who could challenge the military’s ban on gays. Arrangements were made for him to appear on The Rachel Maddow Show to talk about Knights Out and to come out on the air.

On March 19, 2009, Choi was linked by satellite to the Maddow show and told the world, “I am gay.” In a moment of pure irony, as soon as he said the words, Maddow’s show lost the audio and finally cut to a break.

But the die had been cast, and Choi received a letter from the Army dated immediately following the Maddow show. On June 30, 2009, a panel of New York National Guard officers recommended that Choi be discharged from the military despite the fact that every witness on both sides testified that the West Point graduate and decorated Iraqi combat officer was an asset to his unit. The final decision, to be made by the commander of the First Army and the chief of the National Guard Bureau, is still pending. Choi still reports to National Guard duty once a month.

Looking back at his historic coming-out, Choi says he couldn’t fully grasp the reach of his act. “I was just talking to a television camera. And to be honest, it was a lot easier coming out to the world than it was to my parents.”

Choi is now involved in an active campaign to end Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. He has a full schedule of speaking engagements and flies around the country speaking out against the military’s ban. He’s written a letter to President Obama and has received a hand-written response in which the president compares the gay community’s struggle to the civil rights movement, and he was the Grand Marshal of New York City’s 2010 Gay Pride Parade.

“Love Is Worth It”

On March 18 and April 20 of this year, Choi chained himself to the White House fence and was arrested. The first time was a solo act of civil disobedience; the second time he was part of a group. Reflecting on those acts, Choi says, “It was a moment of supreme liberation for me. It was a moment of dignity that you can never really understand when you are just imagining doing it.”

Being in jail was bewildering to Choi at first. “It’s loud, and you are right in there with people who are rapists and murderers. One detective ripped off my name tag and my rank. When we were released the next day to our friends, we were wearing chains and it was hard to move. But being in jail was the validation of everything we learned about civil disobedience in school. There is no greater dignity than spending time in jail.”

Choi says that, looking back, he realizes his life was “one big lie.” “It was a lie taking a girl to the prom, appearing to be heterosexual. It was a lie and a violation of West Point’s Honor Code to pretend to be straight. It was a lie telling members of my battalion that I had a partner named Martha, when his name was

Matthew.”

But the lies have been left behind. Today, Choi is one of the gay movement’s most impassioned young leaders. After a lifetime of repressing his feelings, he is now vocal and unafraid to speak his mind.

The U.S. House of Representatives recently voted to repeal Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. Choi believes that the U.S. Senate will also vote for repeal, despite the threat of filibusters. Repeal of the ban on gays in the military has been linked to the 2011 military budget, and it’s doubtful that opponents of the repeal will vote against the budget.

Still, Choi is far from pleased. “I’ve lost a lot of respect for many people this past year who have shown themselves to be apologists for homophobia.” He is especially critical of President Obama’s compromise on the interim repeal, which allows discrimination and firings to continue. The final enactment of the full repeal requires completion of a study about the issue, and then the signature of the president, the secretary of defense, and the head of the joint chiefs.

“Studies have already been done,” Choi notes. “This [call for another] study is an insult. They are just trying to make it appear that they are doing due diligence. They need to end this study now, eliminate discrimination, and put us on an equal [footing] with everyone else.” Choi says he is especially disappointed that such a compromise came from our nation’s first black president.

Although Choi’s discharge has still not been acted upon, there could be grim consequences. If it were to be approved with anything less than an honorable discharge, Choi would lose his medical benefits, his disability payments, and he would have to repay his West Point education at a cost of $35,000. In addition, he would be banned from any law enforcement, CIA, or FBI job.

Choi says his activism is not just about repealing Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. “It’s a matter of being proud and being dignified. We need to be unashamed of coming out. It’s our duty to show the world that there is hope to live in this world with honesty and integrity. It’s not just about us. It’s a responsibility.

“It’s about love,” he continues. “It’s about acknowledging your number one supporter. It’s about dying in combat and wanting your partner to get the American flag. It’s about National Guard reservists who fall in love and want to [validate] that feeling and their personhood. I tell audiences that love is worth

it. It’s worth it to tell the truth. It’s worth it to risk discharge. In the end, it’s about human dignity. And if you don’t do something, you’re shortchanging the next generation.”

Brandon Wolf is a frequent contributor to OutSmart magazine.

Comments